The slings and arrows of outrage keep flying at Facebook. Today a coalition of child health advocates has published an open letter addressing CEO Mark Zuckerberg and calling for the company to shutter Messenger Kids: Aka the Snapchat-ish comms app it launched in the US last December — targeted at the under 13s.

At the time Facebook described Messenger Kids as an “easier and safer way” for kids to video chat and message with family and friends “when they can’t be together in person” — and said the product had been “co-developed with parents, kids and experts”.

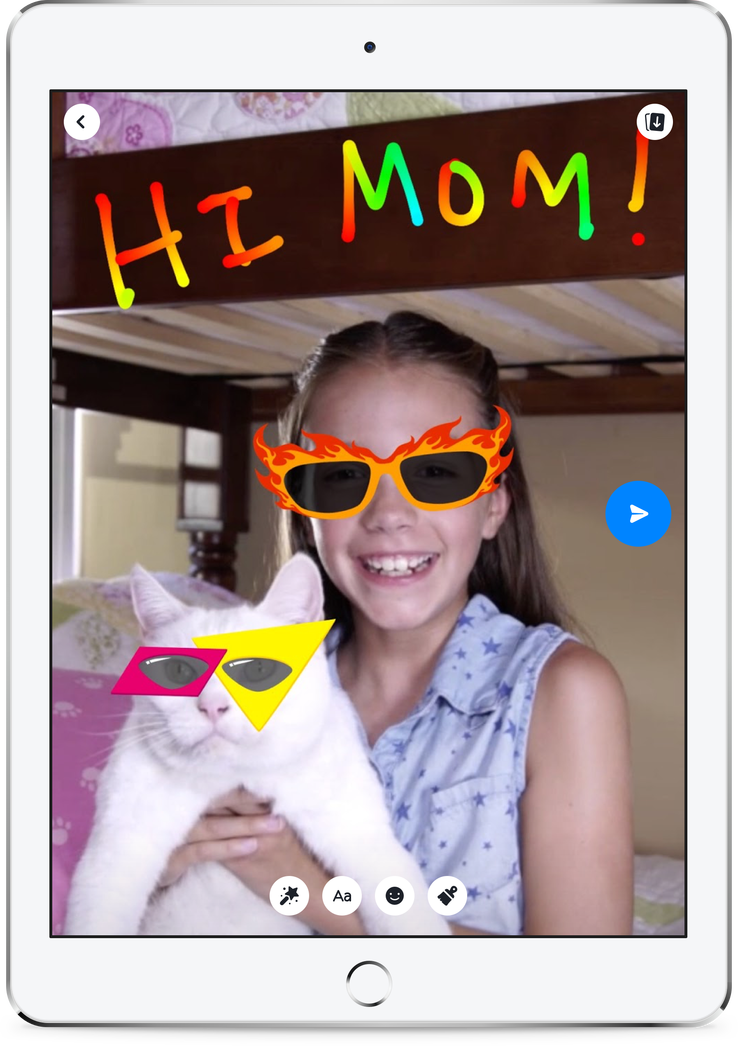

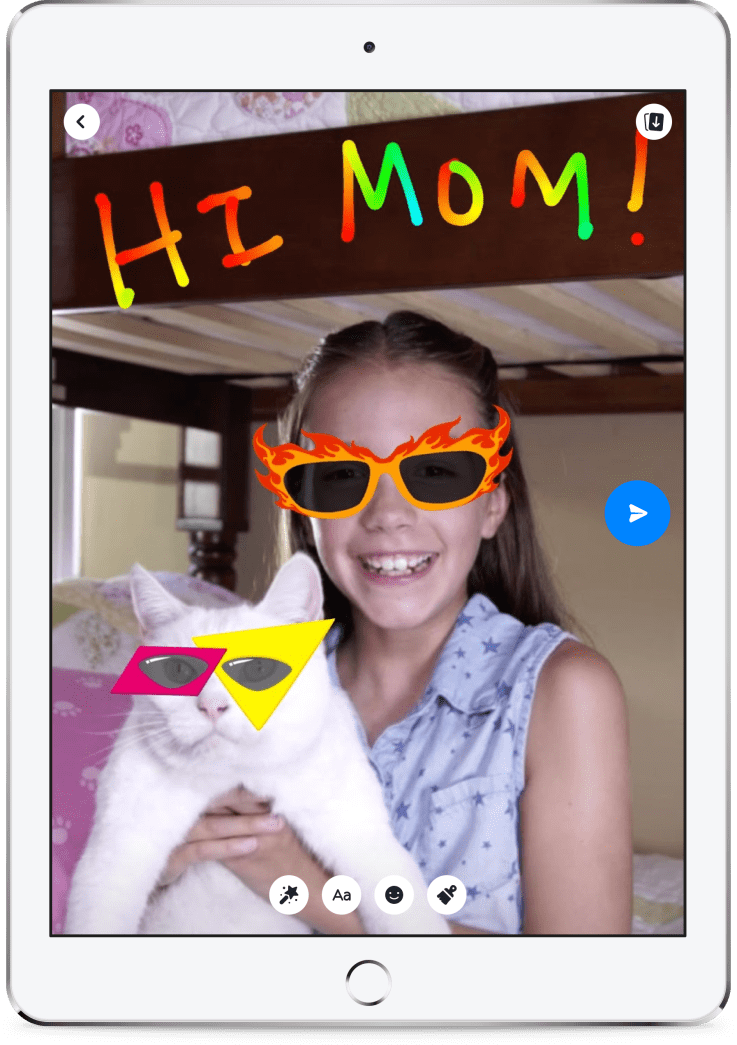

The video chat and messaging app includes a child-friendly selection of augmented reality lenses, emoji, stickers and manually curated GIFs for spicing up family messaging.

At launch Facebook also emphasized there were “no ads” or paid content downloads inside the app, and also claimed: “Your child’s information isn’t used for ads.”

Though that particular message coming from a people-profiling ad giant whose business model entirely depends on encouraging usage of its products in order to harvest user data for ad targeting purposes can only hold so much water. And the company has been accused of trying to use Messenger Kids as, essentially, a ‘gateway drug’ to familiarize preschoolers with its products — to have a better chance of onboarding them into its ad-targeting mainstream product when they become teenagers.

A study conducted by UK media watchdog Ofcom last fall has suggested that use of social media by children younger than 13 is on the rise — despite social networks typically having an age limit of 13-years-old for signups. (In the EU, the incoming GDPR introduces a 13-years age-limit on kids being able to consent to use social media themselves, though Member States can choose to raise the limit to 16 years.)

In practice there’s little to stop kids who have access to a mobile device downloading and signing up for apps and services themselves — unless their parents are actively policing their device use. (Facebook says it closes the accounts of any underage Facebook users when it’s made aware of them.) And concern about the impact of social media pressures on children has been rising.

Earlier this month, for example, the UK government’s Children’s Commissioner for England called for parents to ban their kids from using the Snapchat messaging app — citing concerns over addictive features and cyber bullying.

With Messenger Kids Facebook may well be spying an opportunity to try to outmanoeuvre its teen-focused rival by winning over parents with a dedicated app that bakes in parental controls.

However this strategy of offering a sandboxed environment for kids to message with parentally approved contacts isn’t winning over everyone.

Spearheading a campaign against Facebook Messenger Kids, Boston-based not-for-profit the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood has gathered together a coalition of around 100 child health advocates and groups to sign its open letter. It’s also running a public petition — under the slogan ‘no Facebook for five year olds’.

In the letter the group describes it as “particularly irresponsible” of Facebook to have launched an app targeting preschoolers at a time when they say there is “mounting concern about how social media use affects adolescents’ wellbeing”.

Last week, for example, a study conducted by researchers at San Diego State University found that teens who spent more time on social media, gaming, texting and video-chatting on their phones were not as happy as those who played sports, went outside and interacted with people face to face.

“Younger children are simply not ready to have social media accounts,” the coalition argues in the letter. “They are not old enough to navigate the complexities of online relationships, which often lead to misunderstandings and conflicts even among more mature users. They also do not have a fully developed understanding of privacy, including what’s appropriate to share with others and who has access to their conversations, pictures, and videos.”

They also argue that Facebook’s Messenger Kids app is likely to result in young kids spending more time using digital devices.

“Already, adolescents report difficulty moderating their own social media use,” they write. “Messenger Kids will exacerbate this problem, as the anticipation of friends’ responses will be a powerful incentive for children to check – and stay on – a phone or tablet.

“Encouraging kids to move their friendships online will interfere with and displace the face-to-face interactions and play that are crucial for building healthy developmental skills, including the ability to read human emotion, delay gratification, and engage with the physical world.”

The group goes on to rebut Facebook’s claims that Messenger Kids helps brings remote families closer — by pointing out that a dedicated Facebook app is not necessary for children to keep in touch with long distance relatives, and citing the plethora of alternative options that can be used for that (such as using a parents’ Facebook or Skype account or Apple’s FaceTime or just making an old fashioned telephone call) which do not require kids to have their own account on any app.

“[T]he app’s overall impact on families and society is likely to be negative, normalizing social media use among young children and creating peer pressure for kids to sign up for their first account,” they argue, adding: “Raising children in our new digital age is difficult enough. We ask that you do not use Facebook’s enormous reach and influence to make it even harder. Please make a strong statement that Facebook is committed to the wellbeing of children and society by pulling the plug on Messenger Kids.”

Asked for a response to the group’s call to close down Messenger Kids, a Facebook spokesperson sent us the following email statement — reiterating its messaging around the product at the time it launched:

Messenger Kids is a messaging app that helps parents and children to chat in a safer way, with parents always in control of their child’s contacts and interactions. Since we launched in December we’ve heard from parents around the country that Messenger Kids has helped them stay in touch with their children and has enabled their children to stay in touch with family members near and far. For example, we’ve heard stories of parents working night shifts being able read bedtime stories to their children, and mums who travel for work getting daily updates from their kids while they’re away. We worked to create Messenger Kids with an advisory committee of parenting and developmental experts, as well as with families themselves and in partnership with the PTA. We continue to be focused on making Messenger Kids be the best experience it can be for families. We have been very clear that there is no advertising in Messenger Kids.

Discussing what evidence there is to support concerns over the development impact of digital devices on preschool children, John Oates, a senior lecturer in developmental psychology at the Open University who specializes in early childhood, told us: “The difficulty is that we have very high profile anecdotal cases [of social media concern, where the specific risk is tiny vs the total volume of chats being sent]… But, clearly the harm is potentially great — and the real issue is balancing risks and harm.”

“There is very little large scale evidence around actual developmental impacts on children. And I think that’s a problem — and it’s difficult to know quite how one would research that anyway. In, to isolate cause and effect in this area is really, really difficult. Because children differentially access and use these social media because of their differing profiles — let’s call them personality profiles.

“So some children are more likely to be drawn to use social media and then some of those children are more likely to use it in negative ways, and then some of those children are more likely to be then exposed, as a result, to risk. So the cause and effect chain that’s involved is very complex.”

Oates also points out that younger children, in the 6 to 12 years age range which Facebook Messenger Kids targets, are firstly not necessarily aware of the risks and potential harms, and secondly are also “not cognitively well able to analyze, rationally, the risks and make risk-free decisions”.

“So I think there is a difficulty around all social media in terms of children getting access to it when they’re not aware of the risks. Whether they could be educated better or not is a difficult question — because if they’re not cognitively able to make rational, risk-based judgements… it could be argued that no matter what parents do, and no matter what education does… this is still risky for children,” he said.

The other issue he raises as being a point of discussion and concern for child psychologists is the extent to which extensive use of social media might be a problem by taking children away from other activities that may be more valuable.

“There is a concern there, but there again it comes back to what differences in children predisposed them to get very involved in Snapchat and other social media, Facebook, etc,” he told TechCrunch. “And it seems that one of the main motivations for children is a social one, to feel that they are part of a social group that they can identify with.

“We know that children in this age range are very sensitive to peer approval and peer disapproval. So they’re often quite aware of negative messaging on social media — even if they haven’t experienced it, they’ll know about it. Because this is very salient to them. So it’s really the nature of their social nexus that they form that’s probably the formative element and the messaging within that.”

“It is a real challenge to unpick cause and effect in this area,” he added. “That’s why answering these questions… is extremely difficult. But I think what we can do, on the other hand, is we can draw tentative conclusions from what we do know about children’s development [such as the strong influence of peers].”

Oates also raises the potential of apps that enable children to form social networks digitally (vs only being able to do that face to face) as being a positive change — “for children seeing the world from a whole variety of perspectives and seeing bits of the world that they wouldn’t otherwise see; seeing other children’s points of views and so on and so forth”.

“There’s a lot of potential there and I wouldn’t be just simply negative about this. But recognize that with anything that opens up children’s worlds there are risks as well as benefits,” he added.

This article was updated to specify that the Campaign for a Commercial-Free Childhood is a not-for-profit that has been co-ordinating the campaign efforts against Messenger Kids