Apple unveiled a handful of pro-privacy enhancements for its Safari web browser at its annual developer event yesterday, building on an ad tracker blocker it announced at WWDC a year ago.

The feature — which Apple dubbed ‘Intelligent Tracking Prevention’ (IPT) — places restrictions on cookies based on how frequently a user interacts with the website that dropped them. After 30 days of a site not being visited Safari purges the cookies entirely.

Since debuting IPT a major data misuse scandal has engulfed Facebook, and consumer awareness about how social platforms and data brokers track them around the web and erode their privacy by building detailed profiles to target them with ads has likely never been higher.

Apple was ahead of the pack on this issue and is now nicely positioned to surf a rising wave of concern about how web infrastructure watches what users are doing by getting even tougher on trackers.

Cupertino’s business model also of course aligns with privacy, given the company’s main money spinner is device sales. And features intended to help safeguard users’ data remain one of the clearest and most compelling points of differentiation vs rival devices running Google’s Android OS, for example.

“Safari works really hard to protect your privacy and this year it’s working even harder,” said Craig Federighi, Apple’s SVP of software engineering during yesterday’s keynote.

He then took direct aim at social media giant Facebook — highlighting how social plugins such as Like buttons, and comment fields which use a Facebook login, form a core part of the tracking infrastructure that follows people as they browse across the web.

In April US lawmakers also closely questioned Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg about the information the company gleans on users via their offsite web browsing, gathered via its tracking cookies and pixels — receiving only evasive answers in return.

Facebook subsequently announced it will launch a Clear History feature, claiming this will let users purge their browsing history from Facebook. But it’s less clear whether the control will allow people to clear their data off of Facebook’s servers entirely.

The feature requires users to trust that Facebook is doing what it claims to be doing. And plenty of questions remain. So, from a consumer point of view, it’s much better to defeat or dilute tracking in the first place — which is what the clutch of features Apple announced yesterday are intended to do.

“It turns out these [like buttons and comment fields] can be used to track you whether you click on them or not. And so this year we are shutting that down,” said Federighi, drawing sustained applause and appreciative woos from the WWDC audience.

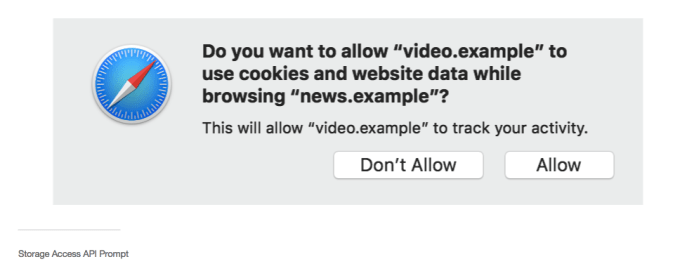

He demoed how Safari will show a pop-up asking users whether or not they want to allow the plugin to track their browsing — letting web browsers “decide to keep your information private”, as he put it.

Safari will also immediately partition cookies for domains that Apple has “determined to have tracking abilities” — removing the 24 window after a website interaction that Apple allowed in the first version of IPT.

It has also engineered a feature designed to detect when a domain is solely used as a “first party bounce tracker” — i.e. meaning it is never used as a third party content provider but tracks the user purely through navigational redirects — with Safari also purging website data in such instances.

Another pro-privacy enhancement detailed by Federighi yesterday is intended to counter browser fingerprinting techniques that are also used to track users from site to site — and which can be a way of doing so even when/if tracking cookies are cleared.

“Data companies are clever and relentless,” he said. “It turns out that when you browse the web your device can be identified by a unique set of characteristics like its configuration, its fonts you have installed, and the plugins you might have installed on a device.

“With Mojave we’re making it much harder for trackers to create a unique fingerprint. We’re presenting websites with only a simplified system configuration. We show them only built-in fonts. And legacy plugins are no longer supported so those can’t contribute to a fingerprint. And as a result your Mac will look more like everyone else’s Mac and will it be dramatically more difficult for data companies to uniquely identify your device and track you.”

In a post detailing IPT 2.0 on its WebKit developer blog, Apple security engineer John Wilander writes that Apple researchers found that cross-site trackers “help each other identify the user”.

“This is basically one tracker telling another tracker that ‘I think it’s user ABC’, at which point the second tracker tells a third tracker ‘Hey, Tracker One thinks it’s user ABC and I think it’s user XYZ’. We call this tracker collusion, and ITP 2.0 detects this behavior through a collusion graph and classifies all involved parties as trackers,” he explains, warning developers they should therefore “avoid making unnecessary redirects to domains that are likely to be classified as having tracking ability” — or else risk being mistaken for a tracker and penalized by having website data purged.

ITP 2.0 will also downgrade the referrer header of a webpage that a tracker can receive to “just the page’s origin for third party requests to domains that the system has classified as possible trackers and which have not received user interaction” (Apple specifies this is not just a visit to a site but must include an interaction such as a tap/click).

Apple gives the example of a user visiting ‘https://store.example/baby-products/strollers/deluxe-navy-blue.html’, and that page loading a resource from a tracker — which prior to ITP 2.0 would have received a request containing the full referrer (which contains details of the exact product being bought and from which lots of personal information can be inferred about the user).

But under ITP 2.0, the referrer will be reduced to just “https://store.example/”. Which is a very clear privacy win.

Another welcome privacy update for Mac users that Apple announced yesterday — albeit, it’s really just playing catch-up with Windows and iOS — is expanded privacy controls in Mojave around the camera and microphone so it’s protected by default for any app you run. The user has to authorize access, much like with iOS.