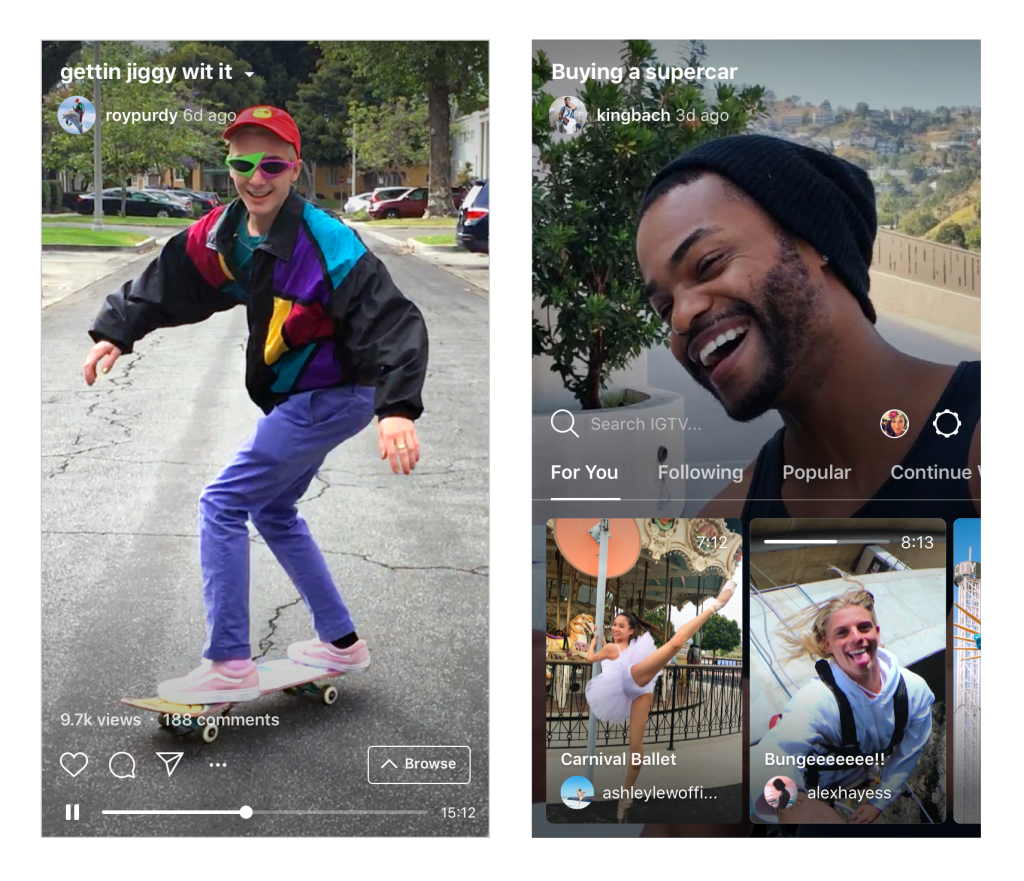

It’s been four months since Facebook launched IGTV, with the goal of creating a destination for longer-form Instagram videos. Is it shaping up to be a high-profile flop, or could this be the company’s next multi-billion-dollar business?

IGTV, which features videos up to 60 minutes versus Instagram’s normal 60-second limit, hasn’t made much of a splash yet. Since there are no ads yet, it hasn’t made a dollar, either. But, it offers Facebook the opportunity to dominate a new category of premium video, and to develop a subscription business that better aligns with high-quality content.

Facebook worked with numerous media brands and celebrities to shoot high-quality, vertical videos for IGTV’s launch on June 20, as both a dedicated app and a section within the main Instagram app. But IGTV has been quiet since. I’ve heard repeatedly in conversations with media executives that almost no one is creating content specifically for IGTV and that the audience on IGTV remains small relative to the distribution of videos on Snapchat or Facebook. Most videos on it are repurposed from a brand’s or influencer’s Snapchat account (at best) or YouTube channel (more common). Digiday heard the same feedback.

Instagram announced IGTV on June 20 as a way for users to post videos up to 1 hour long in a dedicated section of the app (and separate app)

Facebook’s goal should be to make IGTV a major property in its own right, distinct from the Instagram feed. To do that, the company should follow the concept embodied in the “IGTV” name and re-envision what television shows native to the format of an Instagram user would look like.

Its team should leverage the playbook of top TV streaming services like Netflix and Hulu in developing original series with top talent in Hollywood to anchor their own subscription service, but in it a new format of shows produced specifically for the vertically oriented, distraction-filled screen of a smartphone.

Mobile video is going premium

Of the 6+ hours per day that Americans spend on digital media, the majority on that is now on their phone (most of it on social and entertainment activities) and video viewing has grown with it. In addition to the decline in linear television viewing and rise of “over-the-top” streaming services like Netflix and Hulu, we’ve seen the creation of a whole new category of video: mobile native video.

Starting at its most basic iteration with everyday users’ recordings for Snapchat Stories, Instagram Stories and YouTube vlogs, mobile video is a very different viewing environment with a lot more competition for attention. Mobile video is watched as people are going about their day. They might commit a few minutes at a time, but not hour-long blocks, and there are distracting text messages and push notifications overlaid on the screen as they watch.

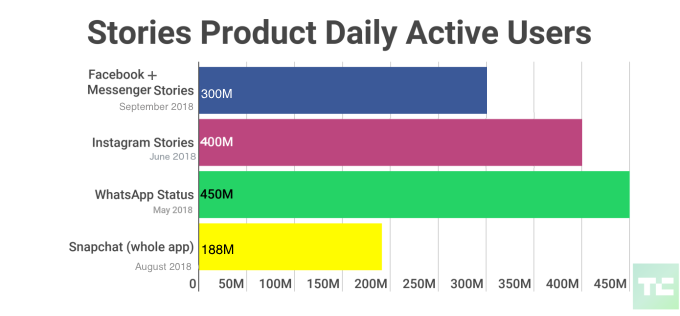

“Stories” on the major social apps have advanced vertically oriented, mobile native videos as their own content format

When I spoke recently with Jesús Chavez, CEO of the mobile-focused production company Vertical Networks in Los Angeles, he emphasized that successful episodic videos on mobile aren’t just normal TV clips with changes to the “packaging” (cropped for vertical, thumbnails selected to get clicks, etc.). The way episodes are written and shot has to be completely different to succeed. Chavez put it in terms of the higher “density” of mobile-native videos: packing more activity into a short time window, with faster dialogue, fewer setup shots, split screens and other tactics.

With the growing amount of time people spend watching videos on their social apps each day — and the flood of subpar videos chasing view counts — it makes sense that they would desire a premium content option. We have seen this scenario before as ad-dependent radio gave rise to subscription satellite radio like Sirius XM and ad-dependent network TV gave rise to pay-TV channels like HBO. What that looks like in this context is a trusted service with the same high bar for riveting storytelling of popular films and TV series — and often featuring famous talent from those — but native to the vertical, smartphone environment.

If IGTV pursues this path, it would compete most directly with Quibi, the new venture that Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman are raising $2 billion to launch (and was temporarily called NewTV until their announcement at Vanity Fair’s New Establishment Summit last Wednesday). They are developing a big library of exclusive shows by iconic directors like Guillermo del Toro and Jason Blum crafted specifically for smartphones through their upcoming subscription-based app.

Quibi’s funding is coming from the world’s largest studios (Disney, Fox, Sony, Lionsgate, MGM, NBCU, Viacom, Alibaba, etc.) whose executives see substantial enough opportunity in such a platform — which they could then produce content for — to write nine-figure checks.

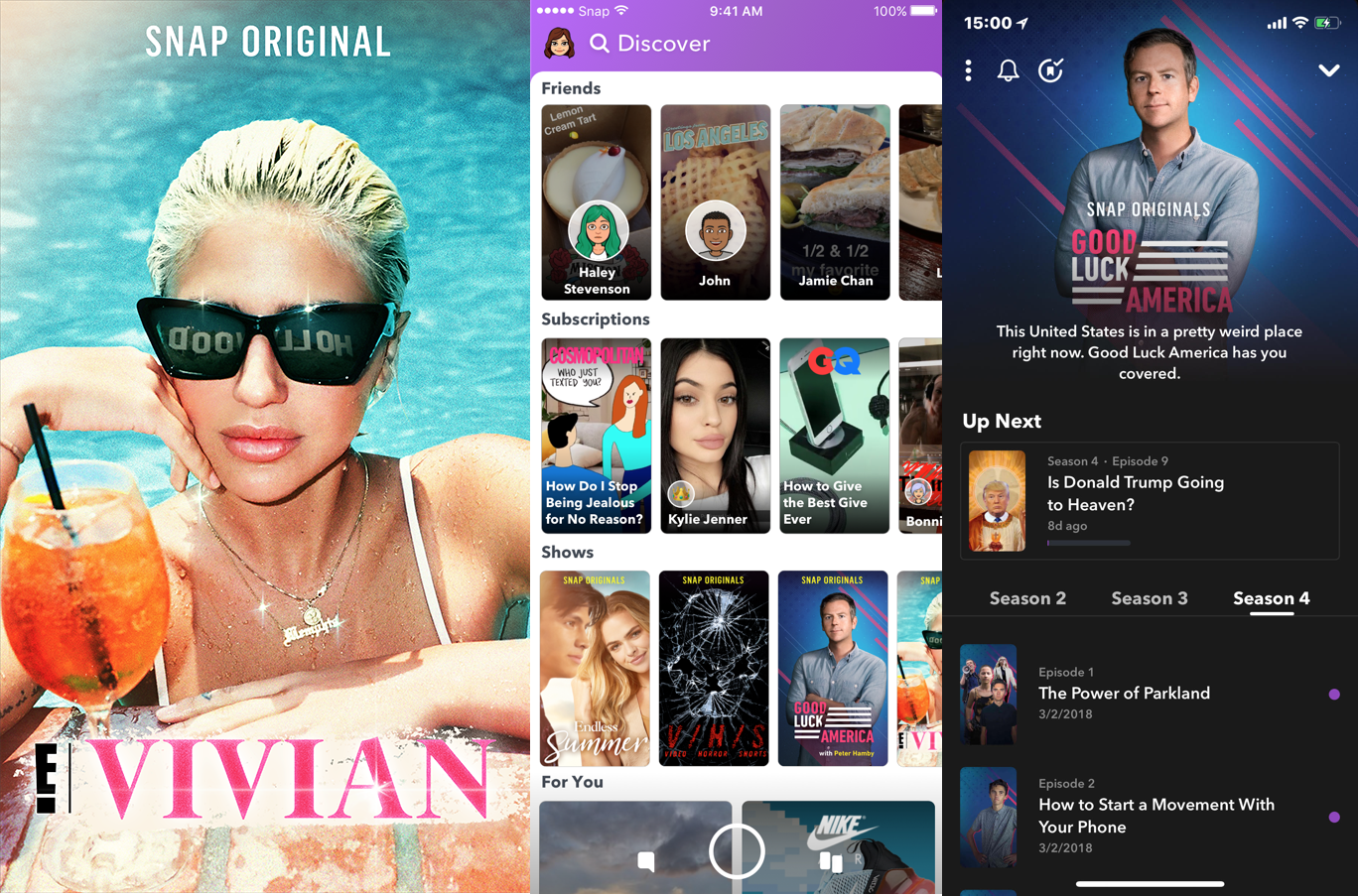

TechCrunch’s Josh Constine argued last year Snapchat should go in a similar “HBO of mobile” direction as well, albeit ad-supported rather than a subscription model. The company indeed seems to be stepping further in this direction with last week’s announcement of Snapchat Originals, although it has announced and then canceled original content plans before.

Snapchat announced its Snap Originals last week

Facebook is the best positioned to win

Facebook is the best positioned to seize this opportunity, and IGTV is the vehicle for doing so. Without even considering integrations with the Facebook, Messenger or WhatsApp apps, Facebook is starting with a base of more than 1 billion monthly active users on Instagram alone. That’s an enormous audience to expose these original shows to, and an audience who don’t need to create or sign into a separate account to explore what’s playing on IGTV. Broader distribution is also a selling point for creative talent: They want their shows to be seen by large audiences.

The user data that makes Facebook rivaled only by Google in targeted advertising would give IGTV’s recommendation algorithms a distinct advantage in pushing users to the IGTV shows most relevant to their interests and most popular among their friends.

The social nature of Instagram is an advantage in driving awareness and engagement around IGTV shows: Instagram users could see when someone they follow watches or “likes” a show (pending their privacy settings). An obvious feature would be to allow users to discuss or review a show by sharing it to their main Instagram feed with a comment; their followers would see a clip or trailer, then be able to click-through to the full show in IGTV with one tap.

Developing and acquiring a library of must-see, high-quality original productions is massively capital-intensive — just ask Netflix about the $13 billion it’s spending this year. Targeting premium-quality mobile video will be no different. That’s why Katzenberg and Whitman are raising a $2 billion war chest for Quibi and budgeting production costs of $100,000-150,000 per minute on par with top TV shows. Facebook has $42 billion in cash and equivalents on its balance sheet. It can easily outspend Quibi and Snap in financing and marketing original shows by a mix of newcomers and Hollywood icons.

Snap can’t afford (financially) to compete head-on and doesn’t have the same scale of distribution. It is at 188 million daily active users and no longer growing rapidly (up 8 percent over the last year, but DAUs actually shrunk by 3 million last quarter). Snapchat is also a much more private interface: it doesn’t enable users to see each others’ activity like Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, YouTube, Spotify and others do to encourage content discovery. Snap is more likely to create a hub for ad-supported mobile-first shows for teens and early-twentysomethings rather than rival Quibi or IGTV in creating a more broadly popular Netflix or Hulu of mobile-native shows.

It’s time to go freemium

Investing substantial capital upfront is especially necessary for a company launching a subscription tier: consumers must see enough compelling content behind the paywall from the start, and enough new content regularly added, to find an ongoing subscription worthwhile.

There is currently no monetization of IGTV. It is sitting in experimentation mode as Facebook watches how people use it. If any company can drive enough ad revenue solely from short commercials to still profit on high-cost, high-quality episodic shows on mobile, it’s Facebook. But a freemium subscription model makes more sense for IGTV. From a financial standpoint, building IGTV into its own profitable P&L while making substantial content investments likely demands more revenue than ads alone will generate.

Of equal importance is incentive alignment. Subscriptions are defined by “time well spent” rather time spent and clicks made: quality over quantity. This is the environment in which premium content of other formats has thrived too; Sirius XM as the breakout on radio, HBO on linear TV, Netflix in OTT originals. The type of content IGTV will incentivize, and the creative talent they’ll attract, will be much higher quality when the incentives are to create must-see shows that drive new subscribers than when the incentives are to create videos that optimize for views.

Could there be a “Netflix for mobile native video” with shows shot in vertical format specifically for viewing on smartphone?

The optimization for views (to drive ad revenue) have been the model that media companies creating content for Facebook have operated on for the last decade. The toxicity of this has been a top news story over the last year with Facebook acknowledging many of the issues with clickbait and sensationalism and vowing changes.

Over the years, Facebook has dragged media companies up and down with changes to its newsfeed algorithm that forced them to make dramatic changes to their content strategies (often with layoffs and restructuring). It has burned bridges with media companies in the process; especially after last January, how to reduce dependence on Facebook platforms has become a common discussion point among digital content executives. If Facebook wants to get top producers, directors and production companies investing their time and resources in developing a new format of high-quality video series for IGTV, it needs an incentives-aligned business model they can trust to stay consistent.

Imagine a free, ad-supported tier for videos by influencers and media partners (plus select “IGTV Originals”) to draw in Instagram users, then a $3-8/month subscription tier for access to all IGTV Originals and an ad-free viewing experience. (By comparison, Quibi plans to charge a $5/month subscription with ads with the option of $8/month for its ad-free tier.)

Looking at the growth of Netflix in traditional TV streaming, a subscription-based business should be a welcome addition to Facebook’s portfolio of leading content-sharing platforms. This wouldn’t be its first expansion beyond ad revenue: the newest major division of Facebook, Oculus, generates revenue from hardware sales and a 30 percent cut of the revenue to VR apps in the Oculus app store (similar to Apple’s cut of iOS app revenue). Facebook is also testing a dating app which — based on the freemium business model Tinder, Bumble, Hinge, and other leading dating apps have proven to work — would be natural to add a subscription tier to.

Facebook is facing more public scrutiny (and government regulation) on data privacy and its ad targeting than ever before. Incorporating subscriptions and transaction fees as revenue streams benefits the company financially, creates a healthier alignment of incentives with users and eases the public criticism of how Facebook is using people’s data. Facebook is already testing subscriptions to Facebook Groups and has even explored offering a subscription alternative to advertising across its core social platforms. It is quite unlikely to do the latter, but developing revenue streams beyond ads is clearly something the company’s leadership is contemplating.

The path forward

IGTV needs to make product changes if it heads in this direction. Right now videos can’t link together to form a series (i.e. one show with multiple episodes) and discoverability is very weak. Beyond seeing recent videos by those you follow, videos that are trending and a selection of recommendations, you can only search for channels to follow (based on name). There’s no way to search for specific videos or shows, no way to browse channels or videos by topic and no way to see what people you follow are watching.

It would be a missed opportunity not to vie for this. The upside is enormous — owning the Netflix of a new content category — while the downside is fairly minimal for a company with such a large balance sheet.