Facebook picked election evening in the U.S. to release a major report on its role in Myanmar, where it is widely accused of failing to prevent its social network from being used to incite genocide.

The situation is arguably more severe than alleged Russia-backed attempts to meddle with the 2016 U.S. election — people have died in Myanmar as Facebook has for years been used to spread hate speech against its minority Muslim population. Yet, Facebook pushed out this independent investigation — available in full here — just hours before the midterms, timing that could see its findings buried as the U.S. political news cycle takes over.

It shouldn’t. There are some serious issues here that need exploring, and not just in the context of Myanmar.

A UN Fact-Finding Mission previously concluded that social media has played a “determining role” in the crisis, with Facebook the chief actor, but there are concerns to answer for in other emerging markets where, like Myanmar, it has happily siphoned advertising money and basked in user growth without taking full responsibility for its position as the dominant internet platform.

In Myanmar’s case, Facebook admitted its failings in a blog post that announced the results of the BSR report into “a human rights impact assessment” of Facebook’s presence in Myanmar, where it is used by nearly 20 million people.

“The report concludes that, prior to this year, we weren’t doing enough to help prevent our platform from being used to foment division and incite offline violence. We agree that we can and should do more,” Facebook wrote.

That’s a positive if not obvious start, but Facebook has been criticized for failing to fully invest in change in Myanmar.

Young men browse their Facebook wall on their smartphones as they sit in a street in Yangon on August 20, 2015. Facebook remains the dominant social network for U.S. Internet users, while Twitter has failed to keep apace with rivals like Instagram and Pinterest, a study showed. AFP PHOTO / Nicolas ASFOURI (Photo credit should read NICOLAS ASFOURI/AFP/Getty Images)

Still no local office

The company confirmed to TechCrunch it doesn’t plan to open a local office, an obvious step that would show it is treating Myanmar seriously.

It believes a local presence would put its staff at risk. The BSR report itself concludes that there would be “both advantages and disadvantages” to a Facebook presence in Myanmar since “the existence of local Facebook staff may increase government leverage over content restrictions and data requests by allowing them to threaten seizure of Facebook’s IT equipment or data or place Facebook staff at safety risk.”

Facebook has been OK taking that risk in a market like Thailand — where it has sat back and watched users routinely jailed for Facebook activity — while its service has been weaponized by controversial Philippines’ President Duterte, and it has come under pressure in Indonesia to censor content and pay taxes, to name but three examples.

“How many companies have 20 million users in one country but don’t have a single employee, it’s absurd,” Jes Petersen — CEO of accelerator firm Phandeeyar, which is part of a civic advisory group to Facebook in Myanmar — told TechCrunch. “An office would go a long way to building relationships with stakeholders.”

Instead, Facebook is building a remote team for Myanmar — with five open vacancies on its careers page.

“Earlier this year, we established a dedicated team across product, engineering, and policy to work on issues specific to Myanmar, and said that we plan to grow our team of native Myanmar language speakers reviewing content to at least 100 by the end of 2018,” it said in its blog post.

However, that push has yet to kick in, according to the report, which pulled two notable quotes from Myanmar-based “stakeholders” interviewed as part of the research. One noted that Facebook’s Myanmar-focused content checkers “need to live and breathe Myanmar and build relationships with a wide range of organizations across Myanmar, not just the usual suspects.”

While another remarked that “at times it feels as if Facebook has outsourced the job to us, but we simply don’t have the resources to do it. We have a strong desire to be collaborative, but not to be relied upon.”

With both complaints, it is hard to see how a remote staff base can adequately address those concerns.

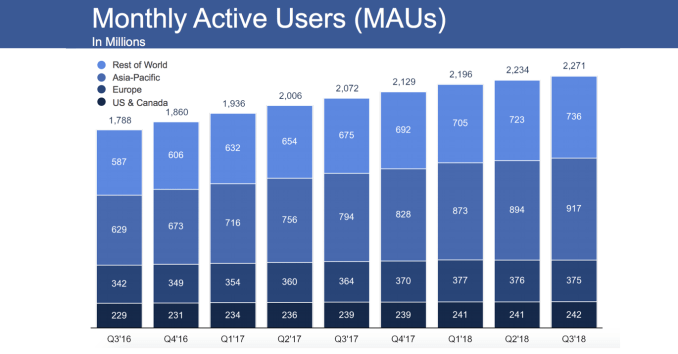

Asia Pacific has become a key growth market for Facebook as user numbers have stalled in the U.S. and Europe

Taking action

Without committing to an office, Facebook has taken significant steps to set an example. It banned 20 individuals and organizations — including armed forces chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and military-owned TV network Myawady — in August after finding evidence that they “committed or enabled serious human rights abuses in the country. Then in October, it booted 13 Pages and 10 accounts — with a cumulative following of more than one million — after a New York Times investigation found they had pedaled government propaganda.

The social network also claims that it is seeing positive change with its efforts to root out content. During Q2, it said it “proactively identified” 63 percent of content that was removed for hate speech in Myanmar, up from 52 percent and 13 percent in the previous quarters.

Petersen, however, suggested that Facebook has been selective with the information it has shared. He said the Myanmar-based group is still waiting on a request for further clarification on a wider selection figures, while Facebook has been less communicative with the group in recent months.

Facebook credits both its hiring of staff and investment in technology for the progress on content, however, it remains unclear how those two factors break down. For one thing, the company has been guilty of over-emphasizing the role its AI-based tech plays in Myanmar.

A previous claim from CEO Mark Zuckerberg that its “systems” prevent hate speech from being sent was roundly rejected by the Phandeeyar-backed group, which helped Facebook identify hate speech on Facebook and Messenger. In response to a public apology from Zuckerberg, the group expressed its frustration that Facebook does “nowhere near enough to ensure that Myanmar users are provided with the same standards of care as users in the U.S. or Europe.”

One area of tech where Facebook is hoping to make a tangible impact is the adoption of Unicode, which is yet to happen widely in the country. More than 90 percent of phones in Myanmar use Zawgyi, but Facebook is dropping support for the standard with the goal of making its safety, reporting and other resources readable — and therefore usable — to all users. It is also improving font converters for those stuck on Zawgyi, it said.

In addition, Facebook said it is working on a digital literacy pilot with Myanmar Book Aid Preservation Foundation and it has partnered with “independent publishers in Myanmar to help build capacity and resources in their online newsrooms.”

Myanmar’s next election is scheduled for 2020, so the company really does need to get its house in order. Petersen, the Phandeeyar CEO, is concerned at to what may happen if progress isn’t made.

“The report does include some good recommendations but this is what everyone told them three years ago. Also, it doesn’t touch on the fact that there’s been a systematic failure on the part of Facebook to address those issues, and that hasn’t changed,” he said. “It establishes an assumption that they’ve engaged with Myanmar strongly before, but they haven’t. Only in the most cursory way.

“There’s an absence of real action from Facebook so far and a risk they’ll continue to not really care at all — and what will happen if they continue to not care?”

A Rohingya ethnic minority man looking at Facebook on his cell phone at a temporary makeshift camp after crossing over from Myanmar into the Bangladesh side of the border, near Cox’s Bazar’s Palangkhali, Friday, Sept. 8, 2017. Tens of thousands more people have crossed by boat and on foot into Bangladesh in the last two weeks as they flee violence in western Myanmar. (Photo by Ahmed Salahuddin/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Great responsibility

In particular, Petersen and the members of the Myanmar-based civic group want the company to look at more localized development features for Facebook products. In the same way that every part of the social network is optimized for engagement and user interaction, so they hope it could tweak its service with the ultimate goal of improving the way it is used in Myanmar.

While Petersen’s ask is likely to fall on deaf ears, the fact remains that Facebook’s failure to be locally aware — both in terms of a team presence and localized product tweaks — are weaknesses that have caused it issues across a number of emerging markets.

Whether that be deaths following fake news on WhatsApp in India, hate speech in Sri Lanka or the issues in Myanmar, it is high time that Facebook take responsibility and develop a truly local strategy rather than generic policies designed in Menlo Park for global usage.

Zuckerberg said earlier this year that “it would be near-sighted to focus on short-term revenue over people.” Even in a “poor” last quarter, Facebook recorded a $5 billion profit, and a logical extension of Zuckerberg’s “people-first” thesis would be a genuine investment in markets where its presence is controversial.

Until we see that happen, Facebook isn’t fully committed to living up to its responsibility.