Not long ago, all of the major innovations came from big research labs in the West. And Silicon Valley not only built the core technologies but also the best applications of these. This is where all the amazing advances happened.

We no longer have a monopoly on disruptive innovation. The cost of building world-changing technologies has dropped exponentially and made it possible for entrepreneurs anywhere to solve the grand challenges of humanity—and disrupt entire industries.

One technology promises to bring quality medical diagnostics to the five billion people in need. I know there are many others.

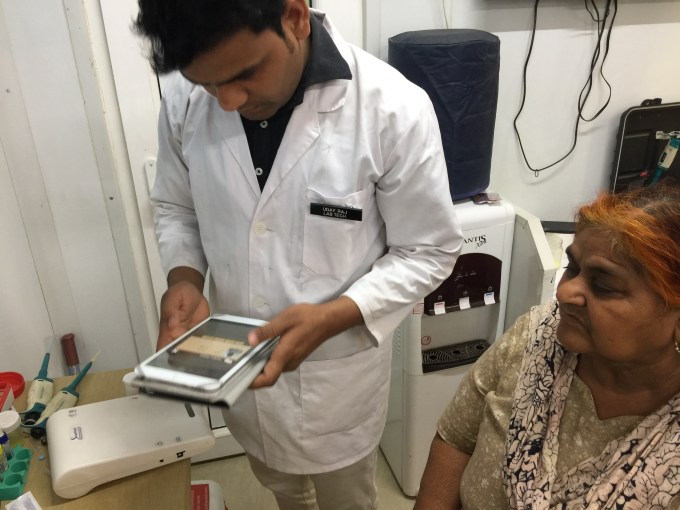

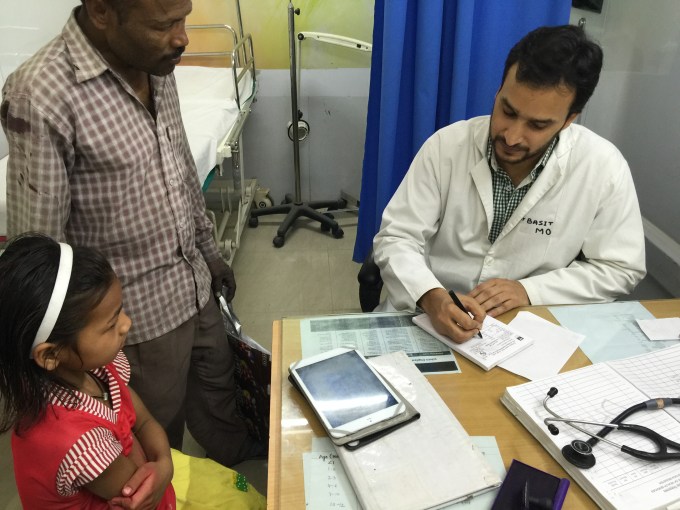

Earlier this month, I went to the Peeragarhi Relief Camp in New Delhi to see Swasthya Slate in action. This is a pilot project for 1000 free medical clinics that Delhi’s chief minister, Arvind Kejriwal, plans to launch.

I was completely blown away with what I saw. The device performed medical tests, including blood and urine, within minutes for 1/100th of what we pay in the U.S. And it integrated into a patient management and AI-based diagnosis system designed for use by minimally-trained front-line health workers. In the one hour that I was there, I witnessed a woman’s life possibly having been saved.

Rupandeep Kaur, 20 weeks pregnant, arrived at the clinic looking fatigued and ready to collapse. After being asked her name and address, she was taken to see a physician who reviewed her medical history, asked several questions, and ordered a series of tests including blood and urine. These tests revealed that her fetus was healthy but Kaur had dangerously low hemoglobin and blood pressure levels. The physician, Alka Choudhry, ordered an ambulance to take her to a nearby hospital.

All of this, including the medical tests, happened in 15 minutes. The entire process was automated — from check-in, to retrieval of medical records, to testing and analysis and ambulance dispatch. The hospital also received Kaur’s medical records electronically. There was no paperwork filled out, no bills sent to the patient or insurance company, no delay of any kind. Yes, it was all free.

The hospital treated Kaur for mineral and protein deficiencies and released her the same day. Had she not received timely treatment, she may have had a miscarriage or lost her life.

This was more efficient and advanced than any clinic I have seen in the West. And Kaur wasn’t the only patient, there were at least a dozen other people who received free medical care and prescriptions in the one hour that I spent at Peeragrahi.

The Swasthya Slate costs only $600. It the size of a cake tin and performs 33 common medical tests including blood pressure, blood sugar, heart rate, blood hemoglobin, urine protein and glucose. It also tests for diseases such as malaria, dengue, hepatitis, HIV, and typhoid. Each test only takes a minute or two and the device uploads its data to a cloud-based medical-record management system that can be accessed by the patient.

This was developed by Kanav Kahol, who was a biomedical engineer and researcher at Arizona State University’s department of biomedical informatics until he became frustrated at the lack of interest by the U.S. medical establishment in reducing the cost of diagnostic testing. He worried that billions of people were getting no medical care or substandard care because of the medical industry’s motivation in keeping prices high. In 2011, he returned home to New Delhi to develop a solution.

Kahol had noted that despite the similarities between medical devices in their computer displays and circuits, their packaging made them unduly complex and difficult for anyone but highly skilled practitioners to use. They were also incredibly expensive — usually costing tens of thousands of dollars each.

He believed he could take the same sensors and microfluidics technologies that the expensive medical devices used and integrate them into an open medical platform. And with off-the-shelf computer tablets, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence software, he could simplify the data analysis in a way that minimally-trained front-line workers could understand.

By Jan. 2013, Kahol had built the device and persuaded the state of Jammu and Kashmir, in Northern India, to allow its use in six underserved districts with a population of 2.1 million people.

It is now in use at 498 clinics there. Focusing on reproductive maternal and child health, the system has been used to provide antenatal care to more than 22,000 mothers. Of these, 277 mothers were diagnosed as high risk and provided timely care. Mothers are getting care in their villages now instead of having to travel to clinics in cities.

At my request, a newer version of the Slate, HealthCube, was tested last month by nine teams of physicians and technology, operations, and marketing experts at Peru’s leading hospital, Clinica Internacional. They tested its accuracy against the western equipment that they use, its durability in emergency room and clinical settings, the ability of minimally trained clinicians to use it in rural settings, and its acceptability to patients.

Clinica’s general manager, Alvaro Chavez Tori, told me that the tests were highly successful and “acceptance of the technology was amazingly high.” He sees this technology as a way of helping the millions of people in Peru and Latin America who lack access to quality diagnostics.

The opportunity is bigger than Latin America, however. When it comes to health care, the United States has many of the same problems as the developing world. Despite the Affordable Care Act, 33 million Americans or 10.4 percent of the U.S. population still lacks health insurance.

These people are disproportionately poor, black or Hispanic, and 4.5 million are children. As a result, they receive less preventive care and suffer from more serious illness — which are extremely costly to treat. Emergency rooms of hospitals are overwhelmed by uninsured patients seeking basic medical care. And when they have insurance, families are often bankrupted by medical costs.

We surely need free health clinics like the ones in New Delhi—with instant diagnosis capabilities and free medicines—in East Palo Alto and parts of Oakland and San Jose. It is sad to see the poverty and exclusion there. And we need these in all over America. But the real opportunity to disrupt the U.S. healthcare system itself.

When I go to my cardiologist for cholesterol tests, for example, he takes a large sample of my blood, sends it to the lab, and calls me back 2-3 days later with the results. And he charges my insurance company a couple of hundred dollars. With the Swasthya Slate they did the same test with a single drop of blood in five minutes—and gave me the results immediately. This cost Rs. 12, that is 18 cents.

I would love to have one of these devices at home and be able to visit my doctors via Skype.

Despite what has become possible, the problems that entrepreneurs in the developing world face is that even the people in their own countries don’t believe that they could have Einstein’s in their midst.

The lesson is that world-changing innovations are happening everywhere now. People in the developing world understand the problems of humanity better than we do. Perhaps it is time for Silicon Valley to start looking abroad for innovations that will better the world.

Featured Image: Kenneth Lu/Flickr UNDER A CC BY 2.0 LICENSE