Cao Xudong turned up on the side of the road in jeans and a black T-shirt printed with the word “Momenta,” the name of his startup.

Before founding the company — which last year topped $1 billion in valuation to become China’s first autonomous driving “unicorn” — he’d already led an enviable life, but he was convinced that autonomous driving would be the real big thing.

Cao isn’t just going for the moonshot of fully autonomous vehicles, which he says could be 20 years away. Instead, he’s taking a two-legged approach of selling semi-automated software while investing in research for next-gen self-driving tech.

Cao, pronounced ‘tsao’, was pursuing his Ph.D. in engineering mechanics when an opportunity came up to work at Microsoft’s fundamental research arm in Asia, putatively the “West Point” for China’s first generation of artificial intelligence experts. He held out there for more than four years before quitting to put his hands on something more practical: a startup.

“Academic research for AI was getting quite mature at the time,” said now 33-year-old Cao in an interview with TechCrunch, reflecting on his decision to quit Microsoft. “But the industry that puts AI into application had just begun. I believed the industrial wave would be even more extensive and intense than the academic wave that lasted from 2012 to 2015.”

In 2015, Cao joined SenseTime, now the world’s highest-valued AI startup, thanks in part to the lucrative face-recognition technology it sells to the government. During his 17-month stint, Cao built the company’s research division from zero staff into a 100-people strong team.

Before long, Cao found himself craving for a new adventure again. The founder said he doesn’t care about the result as much as the chance to “do something.” That tendency was already evident during his time at the prestigious Tsinghua University, where he was a member of the outdoors club. He wasn’t particularly drawn to hiking, he said, but the opportunity to embrace challenges and be with similarly resilient, daring people was enticing enough.

And if making driverless vehicles would allow him to leave a mark in the world, he’s all in for that.

Make the computer, not the car

Cao walked me up to a car outfitted with the cameras and radars you might spot on an autonomous vehicle, with unseen computer codes installed in the trunk. We hopped in. Our driver picked a route from the high-definition map that Momenta had built, and as soon as we approached the highway, the autonomous mode switched on by itself. The sensors then started feeding real-time data about the surroundings into the map, with which the computer could make decisions on the road.

Momenta staff installing sensors to a testing car. / Photo: Momenta

Momenta won’t make cars or hardware, Cao assured. Rather, it gives cars autonomous features by making their brains, or deep-learning capacities. It’s in effect a so-called Tier 2 supplier, akin to Intel’s Mobileye, that sells to Tier 1 suppliers who actually produce the automotive parts. It also sells directly to original equipment manufacturers (OMEs) that design cars, order parts from suppliers and assemble the final product. Under both circumstances, Momenta works with clients to specify the final piece of software.

Momenta believes this asset-light approach would allow it to develop state-of-the-art driving tech. By selling software to car and parts makers, it not only brings in income but also sources mountains of data, including how and when humans intervene, to train its codes at relatively low costs.

The company declined to share who its clients are but said they include top carmakers and Tier 1 suppliers in China and overseas. There won’t be many of them because a “partnership” in the auto sector demands deep, resource-intensive collaboration, so less is believed to be more. What we do know is Momenta counts Daimler AG as a backer. It’s also the first Chinese startup that the Mercedes-Benz parent had ever invested in, though Cao would not disclose whether Daimler is a client.

“Say you operate 10,000 autonomous cars to reap data. That could easily cost you $1 billion a year. 100,000 cars would cost $10 billion, which is a terrifying number for any tech giant,” Cao said. “If you want to acquire seas of data that have a meaningful reach, you have to build a product for the mass market.”

Highway Pilot, the semi-autonomous solution that was controlling our car, is Momenta’s first mass-produced software. More will launch in the coming seasons, including a fully autonomous parking solution and a self-driving robotaxi package for urban use.

In the long run, the startup said it aims to tackle inefficiencies in China’s $44 billion logistics market. People hear about warehousing robots built by Alibaba and JD.com, but overall, China is still on the lower end of logistics efficiency. In 2018, logistics costs accounted for nearly 15 percent of national gross domestic product. In the same year, the World Bank ranked China 26th in its logistics performance index, a global benchmark for efficiency in the industry.

Cao Xudong, co-founder and CEO of Momenta / Photo: Momenta

Cao, an unassuming CEO, raised his voice as explained the company’s two-legged strategy. The twin approach forms a “closed loop,” a term that Cao repeatedly summoned to talk about the company’s competitive edge. Instead of picking between the presence and future, as Waymo does with Level 4 — a designation given to cars that can operate under basic situations without human intervention — and Tesla with half-autonomous driving, Momenta works on both. It uses revenue-generating businesses like Highway Pilot to fund research in robotaxis, and the sensor data collected from real-life scenarios to feed models in the lab. Results from the lab, in turn, could soup up what gets deployed on public roads.

Human or machine

During the 40-minute ride in midday traffic, our car was able to change lanes, merge into traffic, create distance from reckless drivers by itself except for one brief moment. Toward the end of the trip, our driver pushed the lever to trigger a lane change as we approached a car dangerously parked in the middle of the exit ramp. Momenta names this an “interactive lane change,” which it claims is designed to be part of its automated system and by its strict definition is not a human “intervention”.

“Human-car interaction will continue to dominate for a long time, perhaps for another 20 years,” Cao noted, adding the setup brings safety to the next level because the car knows exactly what the driver is doing through its inner-cabin cameras.

“For example, if the driver is looking down at their cellphone, the [Momenta] system will alert them to pay attention,” he said.

I wasn’t allowed to film during the ride, so here’s some footage from Momenta to give a sneak peek of its highway solution.

Human beings are already further along the autonomous spectrum than many of us think. Cao, like a lot of other AI scientists, believes robots will eventually take over the wheel. Alphabet-owned Waymo has been running robotaxis in Arizona for several months now, and smaller startups like Drive.ai are also offering a similar service in Texas.

Despite all the hype and boom in the industry, there remains thorny questions around passenger safety, regulatory schema and a host of other issues for the fast-moving tech. Uber’s fatal self-driving crash last year delayed the company’s future projects and prompted a public backlash. As a Shanghai-based venture capitalist recently suggested to me: “I don’t think humanity is ready for self-driving.”

The biggest problem of the industry, he argued, is not tech-related but social. “Self-driving poses challenges to society’s legal system, culture, ethics and justice.”

Cao is well aware of the contention. He acknowledged that as a company with the power to steer future cars, Momenta has to “bear a lot of responsibility for safety.” As such, he required all executives in the company to ride a certain number of autonomous miles so if there’s any loophole in the system, the managers will likely stumble across it before the customers do.

“With this policy in place, the management will pay serious attention to system safety,” Cao asserted.

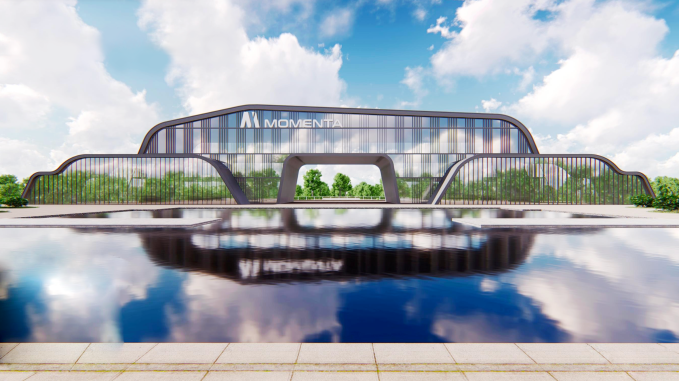

Momenta’s new headquarters in Suzhou, China / Photo: Momenta

In terms of actually designing the software to be reliable and to trace accountability, Momenta appoints an “architect of system research and development,” who essentially is in charge of analyzing the black box of autonomous driving algorithms. A deep learning model has to be “explainable,” said Cao, which is key to finding out what went wrong: Is it the sensor, the computer, or the navigation app that’s not working?

Going forward, Cao said the company is in no rush to make a profit as it is still spending heavily on R&D, but he assured that margins of the software it sells “are high.” The startup is also blessed with sizable fundings, which Cao’s resume certainly helped attract, and so did his other co-founders Ren Shaoqing and Xia Yan, who were also alumni of Microsoft Research Asia.

As of last October, Momenta had raised at least $200 million from big-name investors including Daimler, Cathy Capital, GGV Capital, Kai-Fu Lee’s Sinovation Ventures, Lei Jun’s Shunwei Capital, Bluelake Capital, electric vehicle maker NIO’s investment arm, WeChat operator Tencent and the government of Suzhou, which will house Momenta’s new 4,000 sq-meter headquarters right next to the city’s high-speed trail station.

When a bullet train speeds past Suzhou, passengers are able to see from their windows Momenta’s recognizable M-shape building, which, in the years to come, might become a new landmark of the historic city in eastern China.

Update (June 14, 2019): The article was updated to correct investors’ names and clarify that the driver made a turn by pushing the lever, not steering the wheel.