Tech companies are increasingly finding that accessibility isn’t a widget you plug into an otherwise final product, but something that’s integrated from the very beginning of development — but that takes resources few possess. Fable hopes to make disability-inclusive design easier by providing testing and development assistance from disabled folks on-demand and has raised a $1.5M seed round to do it.

“The person who experiences this problem is usually the best one to solve it,” Alwar Pillai, co-founder of Fable, told TechCrunch. But that’s rarely how it works with accessibility features.

More often than not, she said, the people developing them are able and under 40. “It’s under-prioritized and incomplete,” Pillai said. “It’s not about, is this product really usable by a blind person? Businesses should be consulting with disabled folks, and Fable is a platform that connects digital teams to them so they can include them in building and testing from the get-go.”

Fable provides on-demand access to people with various disabilities that need to be considered during the design process. Prototypes or mockups can be sent to individuals on call, who then return an evaluation within 48 hours.

“Most companies have huge digital products, but no idea what it’s like for people with disabilities, like that a signup flow takes an hour for a blind person,” said co-founder and CTO Abid Virani. “So we put a couple prototypes in front of, maybe, someone quadriplegic or low-vision who has to zoom in a lot, and observe how they go through that. They’ll give feedback on all kinds of stuff you don’t expect.”

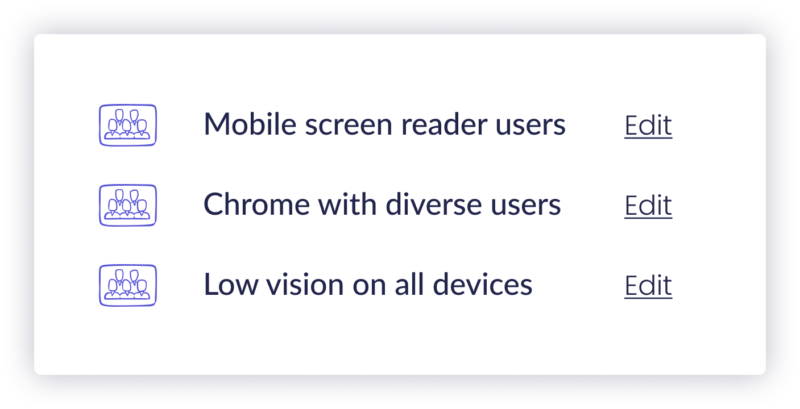

Of course customers can pick and choose which demographics, disabilities and platforms they want to target and test, for example blind users on mobile browsers.

Image Credits: Fable

It’s important, Pillai and Virani emphasized, that this process takes place during development and doesn’t slow it down, otherwise it will be left to the end of development and considered a necessity for ADA compliance rather than actually being about accessibility.

“You can be compliant and still have a bad site,” noted Virani, but companies don’t tend to have the ability to recognize that, since they rarely have disabled testers.

There’s also the consideration that with large products, there are all kinds of integrations, plugins and partners that may or may not be accessible, yet are important parts of the experience. If your ostensibly accessible site hands things over to a payment provider at the last minute that’s difficult to navigate, it’s not really accessible.

That’s throwing away a lot of business, Pillai pointed out. “These are people with billions in disposable income, and they’re untapped,” she said. “It’s a market opportunity.” But only if companies design for accessibility from the start.

Not only that, but with the pandemic creating a shift to working from home, disabilities that were no problem in the office may prove troublesome with remote tools.

In addition to supplying experienced people with disabilities for testing — and providing those people with steady work, which for some can be difficult to come by — Fable is hoping to create and publicize improved testing methodologies and get data out there to improve the status quo.

The company’s $1.5 million round was led by Disruption Ventures in Canada (where the company is based) and Village Global in Silicon Valley. “We wanted people who believed we could do social good and build a billion dollar business,” said Virani.

With the Americans with Disabilities Act having just turned 30 yesterday, it’s clear we’ve come a long way since the ’90s — but not only have we still got a lot of work to do, but it’s ongoing work. Building accessibility and inclusivity into development and testing at a fundamental level should help keep those goals in sight.