Hardware is hard. Building a hardware startup is even harder. The good news is that the staggering amount of innovation in rapid prototyping, 3D printing and backend-as-a-service platforms has made hardware development move at Internet-development speeds. It’s not easy, but it is faster.

When we started our company four years ago, we decided to bootstrap it until we proved there was an actual market for our product. This meant we had to build our alpha version on our own — two engineers and some free time. The world then was different than it is today, but by using the lean startup method and agile development techniques, we were able to bridge the gap and meet our goals, while staying completely self-funded.

Was it the right move? Only time will tell, but it sure was a lot of fun.

Why lean hardware?

Applying the lean startup method is the best way to avoid expensive mistakes. In hardware startups, this is even more important. As makers, it’s so easy to jump straight into design and implementation, but a mistake in the initial definition can haunt you and be very hard to fix later (much more than in software).

To keep us on the right track, we go through fast iterations of LEARN->BUILD->MEASURE. The goal of each iteration is to identify the minimum effort that maximizes learning. Decide what you are measuring, collect a lot of feedback, digest it and move forward.

STEP 1: Research

The basic notion of the lean startup method is that your technology, in and of itself, isn’t interesting. What is interesting is what people do with your product. This is something that is very hard to grasp for us engineers, but the only thing that matters is answering the following three questions:

- What is your product?

- Who is going to buy it?

- Why will they pay you?

Now ask yourself, what’s the fastest way to answer these questions?

That’s right, go talk to potential users and customers. Before you feel you have the answers to these questions, there is no justification to write even one line of code or build any prototypes. During this stage, you need to move in very quick iterations, interviewing five people at each iteration (or 50, depending on your product and customers), reformulate your idea and start asking again. And stick to the process. By doing so, you will remove a lot of bias and maximize your learning.

STEP 2: Build

Once you have that knowledge in hand, it’s time to get cracking on your first hardware MVP (Minimum Viable Product). But don’t forget, we’re here to maximize learning, not build a final product. So start by asking yourself:

- What is it that you need to learn?

- What is the largest risk that you want to mitigate? This could be a technological risk or a user interaction risk.

- What are you going to measure to validate/disprove your assumptions? What kinds of tests can you do?

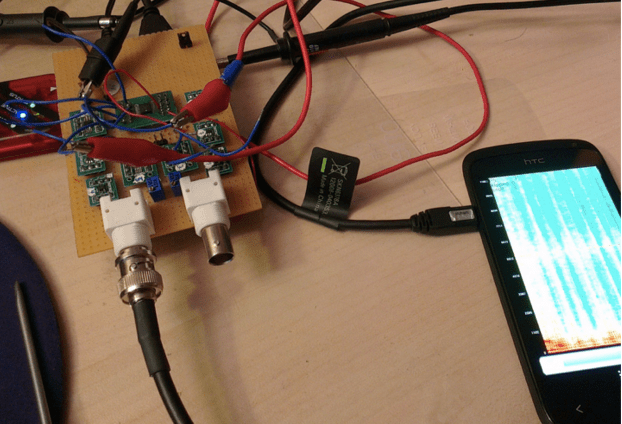

You will probably have a number of iterations in this stage until you get a clear picture of what it is that you’re building and who is going to use it. A rule of thumb here is, if it doesn’t have wires sticking out of it, rubber bands or duct tape, you’ve gone too far. It’s not time to refine the look and feel quite yet, but to get something that works.

STEP 3 : Alpha

Congratulations! You have a working prototype, and you are only somewhat ashamed of the way it looks. Now it’s time to throw it at the market.

Start with smaller test sites. There is a high chance of things not working, having to replace multiple devices and having a harder time demonstrating the immediate value to the users. Use this time to build a relationship with your testers. If you’re really lucky, you’ll build a community that will stay strong and support you when you enter the market.

STEP 4: Beta

After you collect data, both on the product side (usage, engagement, etc.) and on the business side (ROI, price points, user personas), you are ready to move on to your more demanding clients.

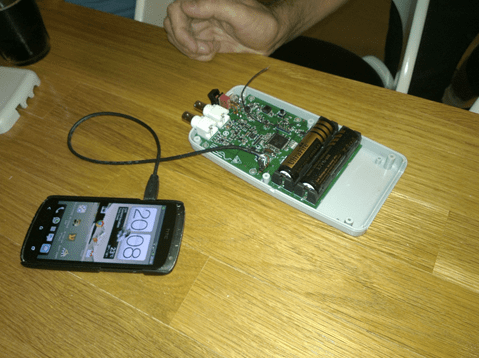

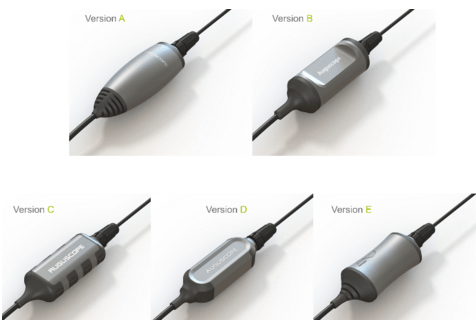

Now’s the time to start the industrial design process. Use prototypes to do real-life testing with potential users, and be sure to involve your existing customers, move fast and iterate. You can use rapid prototyping technologies to experiment with radical designs and do A/B testing — just like you would with software.

Once you have the design down, and you’ve built the electronics to support it, you’re ready for your beta. By this stage you should have nailed down your target market and customers. Make sure your beta users are the same as your target customers — this will maximize your learning. If you can, try to charge for the participation, as this will be a great signal for problem/solution fit. If they’re willing to pay to participate, they’ll likely pay for your product, too.

STEP 5: React. Fix. Improve.

Your product is live, with real-life customers. It may feel like you’ve made it, but the truth is the hard part has just begun. Real users bring real problems: new demands, new use cases and new ways to break your beautiful, fragile product. (“Wait, why would you want to throw it in a puddle?”)

Problems will happen. Leverage the existing relationships you’ve built in order to increase your learning and improve your design. We use what we call react, fix, improve:

- React. React as fast as you can, try to understand what happened and take full blame for it. (Even if the user did something crazy, it’s your fault for not thinking of it.)

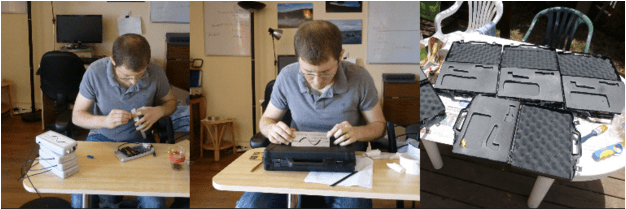

- Fix. Find the quickest way to solve this specific problem for all existing customers. (On multiple occasions, we had a full recall of all of the deployed devices.)

- Improve. Improve your design to make sure this doesn’t happen again and, more importantly, improve your process to make sure you catch problems like this before they happen.

In the end, you’re only as good as your relationship with your customers, so this is your time to shine and prove you’re all about customer support.

During this process you will go through multiple iterations, repeatedly replace old versions and end up with boxes upon boxes of old equipment. At a glance, this may seem wasteful, but this is not waste — this is what progress looks like! Waste would have been designing your final product, manufacturing thousands of it, only to find out nobody cares enough to use it.

STEP 6: Go big

You’ve validated the design, your customers and your users — now it’s time to make a product. Here’s where you put the final touches on the design and start moving from small-scale to large-scale manufacturing.

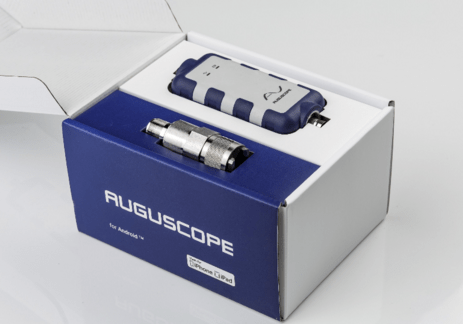

Focus on the small details, like designing a user manual and packaging. Be sure to iterate and user test at this stage, as well — the unboxing experience is a very important part in the users’ life cycle and for brand building. The onboarding material could be crucial to increasing users’ engagement.

Essentially, now’s the time to focus on all those little details you may have glossed over to get a product that works and fits. Make sure all that work won’t go unnoticed and really focus on the user experience.

Summary

Building hardware is hard, but applying lean and agile methodologies could help you avoid catastrophic mistakes and gain early access to your customers. Once you embrace the possibility of failure, you will find out that not all is lost — building a strong relationship with your customers will help you overcome any pitfalls as they arise (and they will).

Like anything in life, you need to plan two steps ahead, focus on the next step and be prepared to move one step back at all times. Happy building!

Featured Image: iurii/Shutterstock