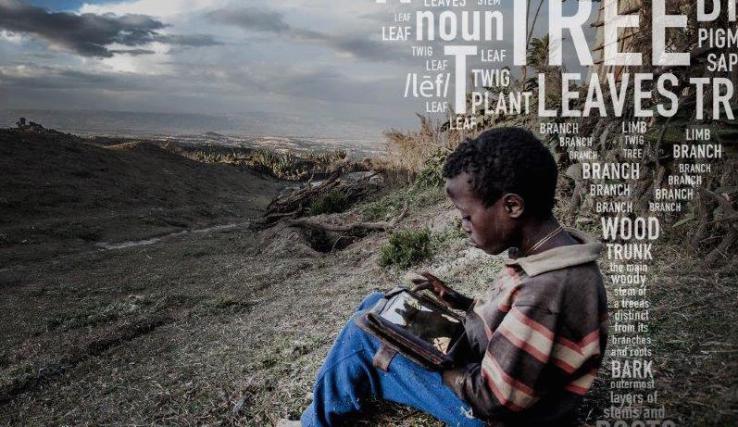

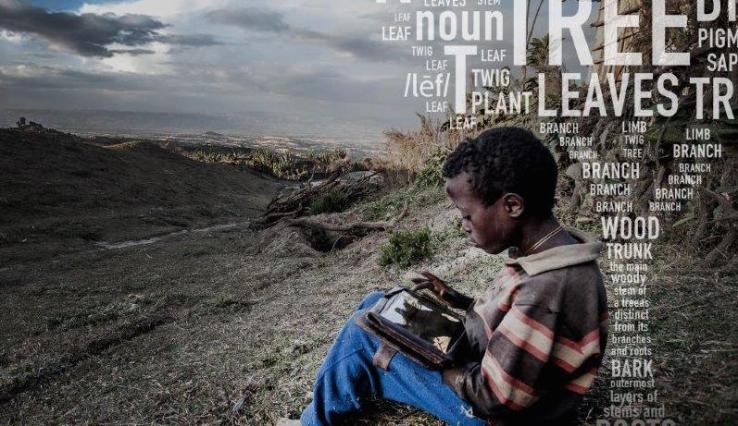

Hundreds of millions of kids around the world lack access to, among other things, basic education — much less organized school systems with adequate teaching resources. XPRIZE is hoping that tech can help where humanitarian efforts have yet to make a dent — and putting $15 million on the line to that end, with the help of Google and the United Nations.

Hundreds of millions of kids around the world lack access to, among other things, basic education — much less organized school systems with adequate teaching resources. XPRIZE is hoping that tech can help where humanitarian efforts have yet to make a dent — and putting $15 million on the line to that end, with the help of Google and the United Nations.

The goal is to create a software and hardware platform that will allow kids anywhere — but in Tanzania, to start — to pursue their own literacy education without the need for any top-down organization whatsoever.

“It’s not a technological problem, but it could have a technological solution,” Matt Keller, lead for the Global Learning XPRIZE, told TechCrunch. “If you can prove children are that intrinsically able to teach themselves and others the fundamentals, it’s part of the answer to an unsolved problem in education.”

It’s still early days for the program: 136 teams from around the world are currently working on submissions for the prize, though ultimately there will be only 5 finalists, each of which will receive $1 million. Submissions are due in November; judging will be finished by next July.

Partners arrive

Today brings new news: Google is getting involved, and will donate 8,000 tablets for the program’s use. And not surplus budget devices, either — they’re Pixel C’s, the current flagship tablet the company designed itself. (I contacted Google for more info on what exactly is being provided, if other software will be included, and so on, but haven’t heard back.)

![]()

The UN is another partner, UNESCO and the World Food Programme, specifically. While aspirants to the prize work on their submissions, these organizations are laying the groundwork for the testing that will come later.

“It’s a lot of legwork,” said Keller, who was in Tanzania himself during the interview. “We need to find villages to work with, brief tribal leaders and elders.”

Joyce Ndalichako, Tanzania’s Minister of Education, Science and Technology, will officially announce the effort in the country.

As other programs have found out, there are problems with dropping millions of dollars worth of cutting-edge electronics into an impoverished and remote area, and I’m not talking about tech support. If people aren’t invested in the program, the tablets will be stolen and sold, along with the infrastructure.

The solar chargers being installed to keep the tablets topped up, for example, organizers had to switch from being specific to the device to being universal and free for anyone to use. By making the tech community property, Keller said, they can mitigate against bad outcomes. Parents, it turns out, become protective of the devices as long as the benefits are clear.

Actual testing will begin in 2017, and will last for 18 months; the team whose app produces the best outcomes will receive the $10 million grand prize.

Promising parallel efforts

This isn’t the first attempt to apply tech to a problem that has its roots in poverty, isolation, and poor living conditions. And while programs like OLPC have had very mixed success, research from the Curious Learning program, a multi-university collaboration, suggests that, with the proper caveats, this approach has the potential to be very beneficial — though it’s far from a complete solution.

The initial results of the program were presented at a conference this week. Tablets loaded with literacy apps were provided to three locations: rural Ethiopia, where no schools or even written language were to be found; suburban South Africa, where a 60:1 student-teacher ratio makes hands-on education difficult; and a rural U.S. school with low-income students — an average Western schooling situation for contrast.

The results are promising: kids as young as 4 who had access to tablets knew more letters and words, second-graders in South Africa likewise had improved vocabulary and reading skills, and the kids in Ethiopia — who had little or exposure to any written language, let alone English — were able to recognize roman characters and identify words by sight.

Small steps, yes, but even the slightest foot in the door is a huge advantage when it comes to early childhood education and literacy. Further testing is now underway in Uganda, Bangladesh, India, and elsewhere in the States.

Soon the group’s findings will be augmented by XPRIZE’s own.

“Human-based schools can’t scale to reach the children you have to reach,” said Keller. “The question is, can technology be used in a way that speaks to the child?”

“The dream,” he said, “is you hand the kid a tablet and you walk away, and they get a world class education.”

Definitely a dream for now, but one that might be inching towards reality. Check back in a few years.