After 20 months in a closed beta under the working title Facebook at Work, (as we predicted it would the other week) today Facebook is finally bringing its enterprise-focused messaging and social networking service to market under a new name, Workplace.

It’s not only armed with a new brand: Workplace is launching with a new kind of pricing model based on Facebook-style monthly active user metrics; and some pretty big ambitions after picking up 1,000 organizations as customers while still in its free, pilot mode (up from 100 a year ago).

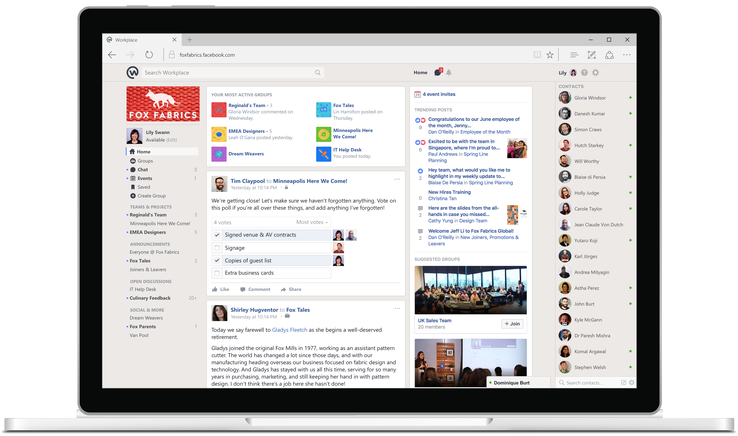

Workplace — which is launching as a desktop and mobile app with News Feed, Groups both for your own company and with others, Chat direct messaging, Live video, Reactions, translation features, and video and audio calling — is now opening up to anyone to use, and the operative word here is “anyone”.

Workplace — which is launching as a desktop and mobile app with News Feed, Groups both for your own company and with others, Chat direct messaging, Live video, Reactions, translation features, and video and audio calling — is now opening up to anyone to use, and the operative word here is “anyone”.

To really gain critical mass for the product and help it stand out from others in the market, Facebook is courting not just companies’ white-collar, desk-dwelling “knowledge workers” who typically buy and use enterprise messaging software.

It also wants to bring on the much wider global wedge of employees who serve customers, maintain machines or otherwise roam as part of their jobs — people who may already be using Facebook in their non-working life, but who have rarely been co-opted into an organization’s wider digital collaboration efforts in the past.

‘We want to build enterprise software the Facebook way’

Workplace is opening for business long after a number of competing services have made their mark and picked up significant traction — popular rival software in the area of enterprise communication and messaging includes the likes of Slack, Yammer (now part of Microsoft), Chatter from Salesforce, Hipchat and Jive, among many others.

There are even a range of lesser-known business messaging apps built specifically for “non-desk” workers, including Zinc (originally called Cotap), Beekeeper and more.

Why the delay? “We had to build this totally separate from Facebook, and we had to test and get all the possible certifications to be a Saas vendor,” Julien Codorniou, director of Workplace, explained in an interview in London, where the development of the product was based. Those developments are still happening. He told me that as of last week Workplace joined the US/EU Privacy Shield.

The other reason has to do with the kinds of companies and non-traditional SaaS buyers it was targeting. “We wanted to see how it would work in very conservative industries and government agencies,” he said. “We had to test the product in every possible geography and industry, especially the most conservative ones. We feel we are ready for primetime now.”

Workplace may not be first to the market, but it’s hoping to woo people with a few twists.

One of these comes in the form of pricing. Enterprise software companies typically follow a few standard business models: they include charging per-seat, based on a certain number of users at your company; in larger tiers based on the same principle of user numbers; based on feature sets; and under a freemium model, where you get a small number of basics for a small group, with the understanding that you soon be ramping up to more features in the paid tiers.

Facebook has thrown most of this out of the window and is opting instead to take a page from its own book of metrics.

It’s going to offer everyone the same features, and charge for Workplace by monthly active users — defined in this case as opening up and using Workplace at least once in the month. Facebook will charge $3 per user per month for the first 1,000 users; $2 for the next 1,001-10,000; and $1 for any MAUs above that.

(As a pricing point of comparison, Slack charges $8 and $15 per active user per month for two bands of features, with the price going down if you pay annually, and it has yet to launch its enterprise tier for extra-large organizations.)

The reason for the pricing by MAUs, and at these competitive prices, was made for a couple of reasons. For starters, it means that what is being bought becomes more transparent to the customer.

But also: Facebook then holds itself more accountable for the service. You pay only for what you are actually using, and Facebook essentially only gets paid for how engaging it’s managed to make the service, much like ads that run on the platform.

“We wanted to build enterprise software the Facebook way,” said Codorniou.

Another interesting aspect of the pricing concerns the tiers of numbers Facebook is throwing around. The company would not give us a total number of MAUs for Workplace as of today. But it is clear that the aim is to target very large companies and other organizations with this product.

Some of the early customers that Facebook has signed up have included 36,000 employees at the carrier Telenor, and 100,000 employees at the Royal Bank of Scotland, and today Facebook’s announcing more such as Danone (100,000 employees), Starbucks (238,000 employees) and Booking.com (13,000).

It also has organizations like the Royal National Institute for the Blind, Oxfam, and the Government Technology Agency of Singapore.

While Facebook is charging for Workplace, making tons of money from it doesn’t appear to be its actual goal — not at first, at least. The goal, Codorniou said, is to gain some critical mass for the product.

“We’re going to grow workplace like Instagram and Messenger,” he said. “Before you even think about monetization, we want to spend the first years growing it. We are obsessed with growth.”

Another way that Facebook might just succeed with at least getting people to try out Workplace, if not switch over to using it permanently, is based on the fact that works just like Facebook itself.

With the main consumer service now pushing past 1.7 billion monthly active users, it’s likely that a good portion of a company’s employees will either already know the service, if not already use it.

This will mean people will be instantly familiar with how the product looks and works, which in the closed beta has translated into a very high amount of engagement with the product. Among the 1,000 companies and other organizations that have been using Workplace in its closed beta, there have been no fewer than 100,000 user groups already created.

‘Usage is more important than a Workday integration’

As we have written about Facebook at Work in the past, much of Workplace will essentially look just like the Facebook you already know and probably use today.

There is a News Feed. There are Groups that you can build within your own company and with colleagues at other organizations that you work with regularly. There is a Messenger equivalent that Facebook refers to as “Chat”.

There is a News Feed. There are Groups that you can build within your own company and with colleagues at other organizations that you work with regularly. There is a Messenger equivalent that Facebook refers to as “Chat”.

There is Live video as well as group video and audio calling. You can comment on posts with multi-emotional Reactions and there are automatic translation features.

There are also some partnerships from day one that speak to the aim of working with big enterprises that may already be using other services. They include the likes of Okta, OneLogin and Ping for log-ins and identity services, Box for storage, and integrators like Deloitte and Sada Systems.

But generally speaking, there isn’t a long list of integrations that will work with Workplace from the start, a la Slack, which lets you bring in work and data from hundreds of other apps with short-cut slash-commands.

Codorniou said that this was intentional.

“We wanted to talk about an easy to use product and democratic pricing with customers,” he said. “When I talked to the CEO of Danone, whose 100,000 employees include many people without computers and desks, usage and engagement were more important than whether Workplace integrated with Workday or Quip.”

(Interesting sidenote to this: for now, Cordorniou told me that Facebook requires all potential sales partners and integrators to actually sign up for Workplace and use it before they are allowed to work on it. “I don’t see how you can sell it without using it first,” he said.)

From what I understand, it’s likely that Slack-style integrations, along with other bells and whistles like bots and the multitude of other features that have invaded Messenger, are likely to come down the line very soon, with the first of them making an appearance at Facebook’s F8 conference this coming spring.

For now, the message to the market may be big enough: Facebook has become a de facto platform for billions of consumers globally to communicate with each other in the digital world, and now it is aggressively moving to be the same in the working world.