The world of prosthetics is advancing in two directions: on one hand, if you will, the latest in soft robotics and shrinking sensors enables limbs and digits with ever-increasing levels of sensation and realism. On the other, rapid manufacturing techniques are making it possible to bring sophisticated designs to the underprivileged and geographically isolated. Po is a company in Paraguay pursuing the latter goal, making customized prostheses for people who might otherwise have never gotten anything at all.

Paraguay, as described to TechCrunch by Po co-founder Eric Dijkhuis, is “a country full of amazing people but also a lot of challenges. There is a high number of amputations per day, upper limbs being a high percentage of them, due to a lack of work safety regulations combined with vulnerable working areas, and a lot of motorcycle accidents.”

Widespread low income also means very few people can afford the kind of prosthesis they need — less than 3 percent, Dijkhuis said. Why should that be, Po’s founders thought, in an age when you can print objects into existence and get advanced control systems off the shelf?

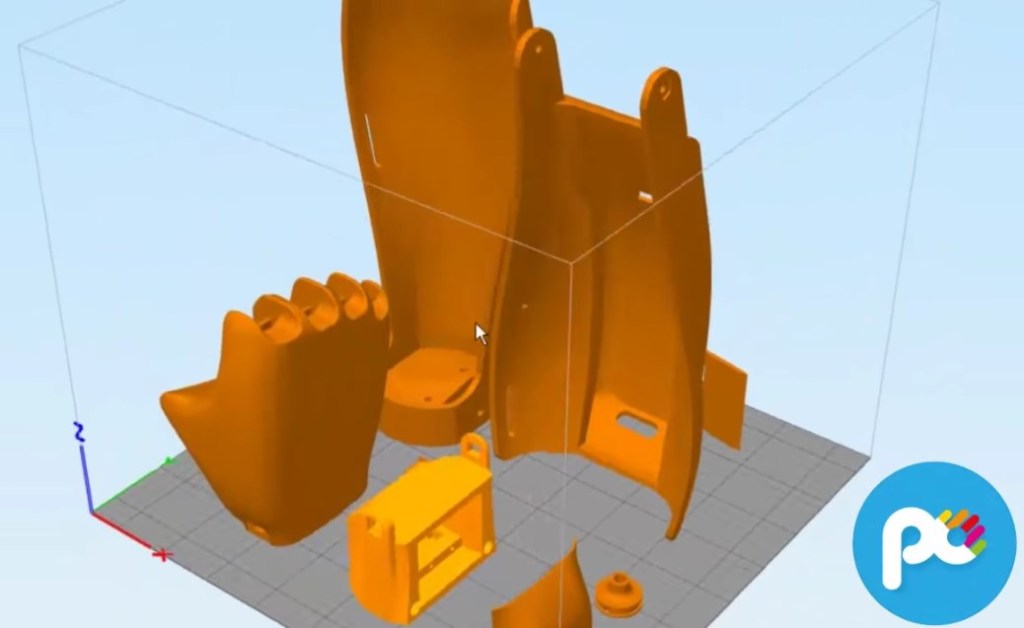

So they got to work designing a durable, printable prosthetic hand and lower arm that can be tweaked and customized in terms of size, color and other basic parameters. There are over 100 Po hands out there being used right now that are controlled mechanically, but the team had a eureka moment when they met with Thalmic Labs about that company’s Myo device.

You may remember Myo: It fits around your arm, monitoring your muscles for bioelectric signals that coincide with various motions and passing that data on wirelessly to other devices. So making a fist or tilting your hand up could, for example, minimize the window on your laptop, or switch applications — or, in the case of a prosthesis, simply mirror that action with the artificial limb.

Now Po has five people testing MyPo, a combination of the original mechanical arm and a Myo control mechanism.

“At a fraction of the cost, MyPo mirrors the traditional functionality of a prosthetic hand,” said Dijkhuis, “including several grips, degrees of freedom, and it can even integrate applications that already exist with the Myo armband.” So in addition to picking up and manipulating objects, gestures can be built into interact with social media, music apps and so on.

This last is a capability being investigated by others, as well: German designers recently created a Myo-powered accessory that fits onto existing prostheses and allows for this kind of interaction.

An advantage of using the Myo as a limb control mechanism is that it can tie the motion of the hand directly to the gestures and muscular activity already learned for that motion. So although the user may not have fingers to make a fist, their motor memory of the way they did it remains, and the Myo can detect it and respond.

“They think, they remember, they do, and the Myo armband guides the whole process amazingly,” said Dijkhuis.

Po isn’t the first or only 3D-printed prosthesis, of course — many have been made already. But it’s not enough to simply make a design. There’s the matter of fitting, configuration and the cost of the components.

“We we help the user pay a figurative amount that they can afford by subsidizing the rest through private donations,” Dijkhuis explained. “We also work with independent professionals, NGO’s, allied businesses and public organizations that support our work. Our model is currently being replicated in North Argentina and South Brazil by Po partners, but our entire workflow is going to be open so anyone can start their own chapter with standardized, ready to go procedures.”

Meanwhile, the whole thing is up on Thingiverse, where you can download it, tweak it, make suggestions or perhaps try one out for yourself.

This isn’t a particularly high-profile application of technology, since the users aren’t tech-savvy urbanites and the companies and services don’t command billion-dollar valuations. But getting a prosthetic hand to a child too poor to afford one is a goal worth shouting about.

“Creating and developing Po, we have seen the power of leveraging new technologies, like 3D printing, the Myo armband, and the power of open source,” said Dijkhuis. “We believe that these technologies applied to social impact are not only disrupting an industry, but are rewriting the rules of the game for the future of prosthetics, and handing the power of innovation to people all around the world.”