An Illinois law is proving a thorn in Facebook’s side as a class action lawsuit, alleging mishandling of biometric information, moves toward trial. The latest developments in the case have the social network objecting against releasing or even admitting the existence of all manner of data, but the plaintiffs aren’t taking “objection” for an answer.

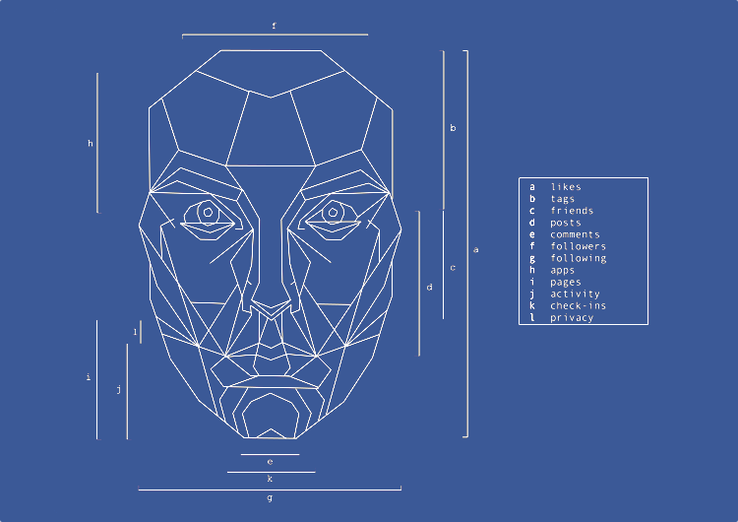

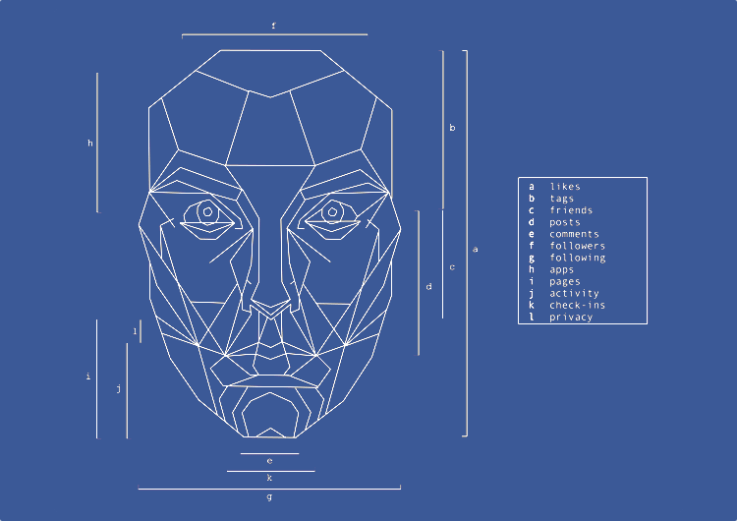

The case revolves around a 2008 state law known as the Biometric Information Privacy Act. BIPA basically makes it illegal to collect or use biometric data, such as a “scan of hand or face geometry,” without rigorous disclosure of methods, intentions and guarantees regarding that data. The class action suit, filed in mid-2015, alleges that Facebook has knowingly failed to perform this disclosure for its many Illinois users.

Separate suits have been filed against Shutterfly, Snapchat and Google. The Shutterfly suit was settled, and Snapchat’s sent to arbitration. The Google case is technically ongoing, but the company argues that analysis of digital photos doesn’t count as biometric data, nor could an Illinois law prevent a California company from performing such analysis outside Illinois. Facebook has likewise fought the suit, aiming for dismissal under similar arguments.

The clear-headed Judge James Donato determined in May that while proceeding under California law was something users had agreed to, it was unenforceable, as it would amount to “a complete negation” of non-California protections such as those found in BIPA. And as for the idea that a “scan” must take place in person, he called that interpretation “cramped” and noted that the law itself is so worded as to potentially include such “emerging” methods as bulk digital analysis. So the case proceeded, and the parties at odds have fallen to squabbling over the details.

Specifically, the plaintiffs say that Facebook must provide documents regarding the lobbying effort against BIPA that suddenly began after the case failed to be dismissed — State Senator Link proposed an amendment (at the urging of such lobbyists, opponents alleged) that would exclude digital images from BIPA provisions. The amendment was never adopted, but we intend to look into it nevertheless, as its changes would have been suspiciously beneficial to the companies under threat from the law as it stands — and who claimed to not be subject to it anyway. Documents from a case in Ireland with some similarities are also requested, as are some related to patents and source code surrounding Facebook’s facial recognition technology.

Facebook, for its part, has objected to just about every word in the dictionary. In a document filed in September, Facebook objects to the definitions of: biometric identifiers, faceprint, face Template, face recognition, face finding, stores, name and location, user, created, uploaded, relevant time period, Facebook, defendant, you, your, and in fact all other “definitions” and “instructions” in the plaintiff’s interrogatories.

Facebook denies the implication that it has created, stored or used any biometric identifiers whatsoever, even though it’s beyond a doubt that it does, by any reasonable definition of the terms. It also claims that it does not maintain records on whether photographs contain people, a claim that seems at odds with basic facts regarding how its tagging and facial recognition processes work.

There are legitimate objections, as well, of course: a request for a printed copy of the source code is indeed “frivolous,” for instance, and although Facebook tracks location, it doesn’t necessarily know the legal residence of a given user, so requests for that (critical for a class action relying on state jurisdiction) are also unable to be fulfilled.

The company also offers some rather thin-sounding excuses, dismantled convincingly by the plaintiffs, as to why it can’t provide information on its lobbying efforts against the law it is accused of violating, as well as documents related to the Ireland case. And, as the plaintiffs point out, what few documents it has provided are often heavily redacted. A public version of one redacted document was found, in fact, and the redacted information was far from confidential — the plaintiffs argue — highly relevant. It doesn’t speak well for the other redactions, they say.

I am not a lawyer, of course, but the court records show Facebook in a poor light: evasive, pedantic and stalling for time. It is understandably wary of exposing the inner workings of its facial recognition systems to an unsympathetic judge in a state with strong protections against practices it is conceivably (some would say assuredly) taking part in. And the repercussions of a company whose services transcend borders being forced to conform to a state law like this could be far-reaching.

I am not a lawyer, of course, but the court records show Facebook in a poor light: evasive, pedantic and stalling for time. It is understandably wary of exposing the inner workings of its facial recognition systems to an unsympathetic judge in a state with strong protections against practices it is conceivably (some would say assuredly) taking part in. And the repercussions of a company whose services transcend borders being forced to conform to a state law like this could be far-reaching.

But time is running out: The deadline for discovery is in early February, and it’s hard to see how Facebook can continue to balk at providing some of the documents in question without provoking the ire of the judge. A call is scheduled for January 5 to resolve some of these disputes, and Facebook’s next court filing may successfully object to the objections to the objections to the objections mentioned above (but we’ll leave that to the judge to decide).

I’ve contacted both Facebook and the law firm representing the plaintiffs — Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd — and will update this post if either offers any comment. We will also be following this case as it develops, as it could prove a landmark one in terms of how biometric data is handled and disclosed by major companies like Facebook.