Aiming for the stars and not quite making it, the ambitious App.net has finally officially shut down. Its timely rise and fall comes as highly symbolic as its once rival, Twitter, continues to struggle, years later, with monetization, content management and harassment.

Today’s announcement of its closure isn’t hugely surprisingly since App.net had been in “maintenance mode” since May 2014. CEO Dalton Caldwell and his co-founder Bryan Berg put the social network on autopilot after it failed to generate the revenue necessary to support a full-time staff. Caldwell subsequently took on a new role as a partner at Y Combinator.

Dalton Caldwell, co-founder and CEO of App.net

To the team’s credit, App.net grew organically out of a successful crowdfunding campaign that surpassed $750,000 in pledges. A strong community bought into the promise of an ad-free, subscription-based, Twitter clone that would remain friendly to developers and users, no matter how big it got.

Unfortunately for everyone, the network just didn’t make money. By the time App.net got off the ground in 2012, Twitter already had six years of momentum and user growth.

By 2013, App.net needed institutional capital to make the fight competitive. Andreessen Horowitz bankrolled a $2.5 million venture round for the company on its own.

App.net sought to distance itself from Twitter by focusing in on building just the bare bones of a social platform that developers could build on top of. Caldwell and Berg toyed around with a number of different monetization models from slightly free to even less free.

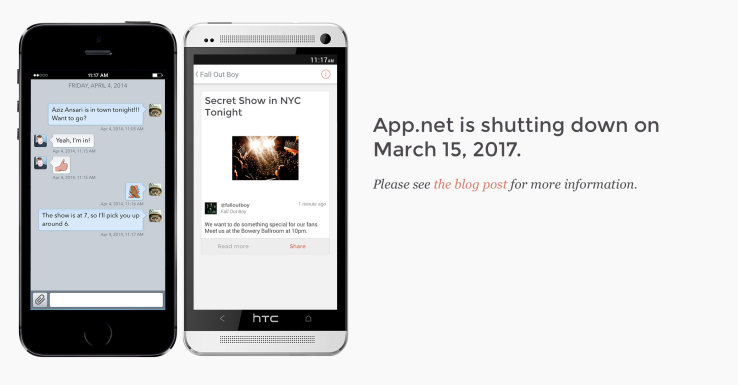

The company will finally be laid to rest on March 14th, 2017, when the ability to signup and renew subscriptions will end. Caldwell did note in a blog post that the code for App.net will be open-sourced. After the 14th, all user data will cease to exist.

Caldwell gave the following reflection on the App.net blog:

Ultimately, we failed to overcome the chicken-and-egg issue between application developers and user adoption of those applications. We envisioned a pool of differentiated, fast-growing third-party applications would sustain the numbers needed to make the business work. Our initial developer adoption exceeded expectations, but that initial excitement didn’t ultimately translate into a big enough pool of customers for those developers. This was a foreseeable risk, but one we felt was worth taking.

To onlookers in 2017, the project brings memories of simpler times — before the infamy of fake news, before Snapchat selling hardware was cool and before the platformization of social networks become commonplace. Today, there is still energy in the notion of improving the quality of our social networks. People still want greater privacy and control, but few are willing to pay for it.

App.net might have had a better run if it more fully differentiated itself from Twitter. With so much in common, Twitter suffocated it, leaving almost no room for user acquisition or market cannibalization. With more creative models, Snapchat and Instagram steamed ahead, while App.net didn’t.

As content monetization continues to grow in importance for Twitter and others alike, there’s perhaps no better time to reflect on the lessons of App.net. Now isn’t the time to further divide our social networks into paid and unpaid communities, it isn’t the time for some folks to have access to vetted content and others to be unknowingly left behind. It’s the time for Twitter and the rest of the socialsphere to make good on what the App.net community wanted from the beginning — user-first social networks. There’s no reason to think that won’t bring everyone more revenue in the process.