A bible for photographers. That is how Robert Capa described The Decisive Moment by Henri Cartier-Bresson. After almost 70 years it was first published, this book has still a lot to say to photographers and especially to street and documentary photographers.

The book said to be an essential one for any photography collection. But is it? I am going to give you this brief overview of this legendary book.

Henri Cartier-Bresson is said to be a founder of modern photojournalism. I have actually talked about his life and photography in one of my very first videos. He actually came up with this idea of the “decisive moment.” I wouldn’t say he invented it but he definitely gave it a name and introduced it to a wider audience.

Here’s what Cartier-Bresson told the Washington Post in 1957:

Photography is not like painting. There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative, oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.

The book was published in 1952 originally titled Images à la Sauvette (“images on the run”) in the French, published in English with a new title, The Decisive Moment. The words were actually taken from a quote by the 17th century Cardinal de Retz, who said, “There is nothing in this world that does not have a decisive moment.”

You can find the first edition on eBay for $1,000 and more depending on the condition. It was printed in 10,000 copies; 3,000 of the French edition and 7,000 of the American edition. The original price was actually $12.50 in North America.

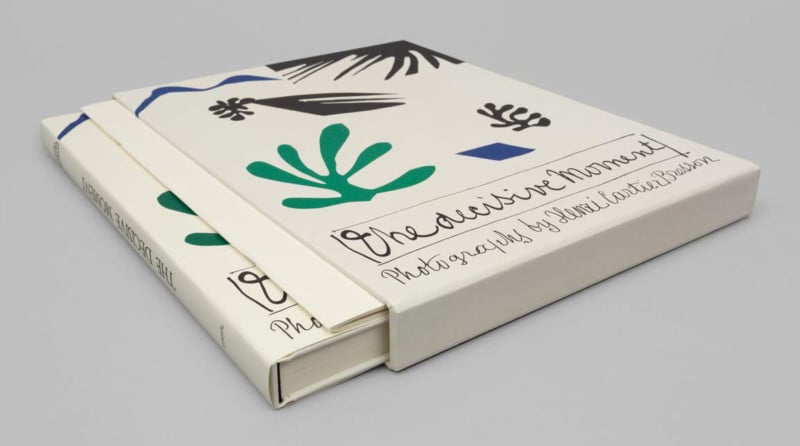

The new print run of the book has a hardback and extra hard case to house the book itself and a pamphlet that I will talk about later.

The artwork on the case and on the book itself is an artwork by Henri Matisse — it’s not a photograph but a signature cut-out of Matisse.

![]()

In the top right, we can see the sun that shines over the Blue Mountains. In the middle is a bird holding a branch. Then there are a few green and black vegetal forms and a stone at the bottom. On the back cover, we can see color sparkles of green and blue. The spirals are supposed to evoke the pace of time.

![]()

What is interesting about this cover is that when you look closely, the name Cartier-Bresson is actually missing the hyphen. I don’t actually know why that is. Maybe Matisse forgot to draw it there and then they just didn’t want to tell him to fix his artwork. The pamphlet suggests that the missing hyphen could be deliberate, as if Matisse wanted to express Cartier-Bresson’s duality and his shifting temperament.

The book is pretty big. Even without the case, it is the biggest book I own. It is 37x27cm so the ratio works for photographs of 24×36 photographic film Cartier-Bresson used. Each page can fit one horizontal photograph or two vertical ones. The pages are stitched in a way that allows proper flat opening. It has 160 pages with 126 photographs and weighs over 5.5lbs/2.5kg.

The pamphlet is a very nice behind-the-scenes book composed of quotes by Henri Cartier-Bresson and some other information about how the book was made. It tells the story of Cartier — Bresson working on the book, the sequencing, work with the publisher, the story of the cover, and so on.

The publisher insisted that the images should be matched with a text in the book. The idea was to provide technical and “how-to” information, but it was something Cartier-Bresson wasn’t fond of too much.

The book starts with an introduction by Henri Cartier-Bresson followed by photographs split into two sections, chronologically and geographically. The first one contains photographs taken in the West from the years 1932 to 1947. The second contains photographs taken in the East from 1947 to 1952. Since the introduction wasn’t technical enough, there is also a technical text by Richard L. Simon at the end of the book, which was only included in the American version.

We can also consider the two sections to be the phases of Cartier-Bresson’s carrier. During his career, Cartier-Bresson oscillated between art and photojournalism. It is obvious from his photographs before he joined Magnum and after that. When selecting the photographs, Cartier-Bresson clearly favored the reportage images he made as a member of Magnum Photos as some of his well-known images like Hyeres, France, 1932 (AKA The Cyclist) from the early 30s are missing.

As The Decisive Moment was published 5 years after he joined Magnum, he left out a lot of his surrealism inspired images and used more of his photojournalism work, especially in the second section which displays only Magnum images. Those photos also have much longer captions as they were mostly shot for press.

The book is evidence of Cartier-Bresson’s shift from art to photojournalism during that time. He would later switch back when he focused on exhibitions and wanted to be perceived more as an artist rather than a photojournalist.

All photographs are in black and white, as Cartier-Bresson didn’t like to shoot colors. He saw color as technically inferior (due to the slow speeds of color films) as well as aesthetically limited.

At the time the book was published, it was immediately clear the book was unique, not only in terms of size but also quality. Even though it was accepted very well by critics, the first sales were not so good: that was the reason there was never the second print (prior to 2015).

“The Decisive Moment” wasn’t actually the only title Cartier-Bresson considered. One of the favorite possible titles was “À pas de loup” (“Tiptoeing”), which expressed the way in which Cartier-Bresson approached those whom he photographed. “The subject must be approached tiptoeing,” he once said.

The second possible title was “Images à la Sauvette” (roughly translated as “images on the run”), which ended up being the name of the French edition, related to small street vendors ready to flee when being asked for their license. It also expressed his concept of photography.

My favorite picture from the book is one from Kashmir showing Muslim women on the slopes of Hari Parbal Hill in Srinagar praying toward the sun rising behind the Himalayas.

The #ICPMuseum is the first venue in the United States to present “Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Decisive Moment.” The exhibition shares the behind-the-scenes story and offers a rare chance to see first edition printing. https://t.co/blKiNC0Wgo 📷 Srinagar, India, 1948 pic.twitter.com/UJY54xTG3P

— ICP (@ICPhotog) July 9, 2018

As you see when you look at Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs, he adapted many styles. When I first saw this photograph, I just thought how timeless it looked. It could easily be taken thousands of years ago if cameras had existed then. Cartier-Bresson shot some very important events but also some casual photos.

I think The Decisive Moment an amazing book even though it is expensive. But the valuable information it provides and the forms makes you really feel like you are holding a piece of history. It would be a great gift for any photographer but especially for someone shooting a street or documentary style.

About the author: Martin Kaninsky is a photographer, reviewer, and YouTuber based in Prague, Czech Republic. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Kaninsky runs the channel All About Street Photography. You can find more of his work on his website, Instagram, and YouTube channel.