![]()

If the number of obituaries written about someone is any measure of their impact on society, Janet Malcolm was a heavy hitter. Google lists more than 40,000.

Before passing in 2021, Malcolm was a staff writer at the venerable New Yorker magazine for almost 60 years; she became the consummate journalist and E. B. White’s literary heir.

She had a signature detail-driven style and an analytical curiosity about everything. As the magazine’s first Photography Editor she would, in time, join Walter Benjamin, John Berger, Susan Sontag, and Roland Barthes as elite photography critics. How she came to encourage photographers to follow their own creative instincts is the kernel of this book.

Her photography essays were, on the surface, reviews of photo exhibitions and books that investigated “how and why a person aiming a camera a certain way at a certain segment of visual reality will occasionally, mysteriously make a work of art.” They shaped Malcolm’s thoughts on photography. The modest explanation was “I began to get hold of the subject midway through the essays and by the ninth one, “Two Roads”, I could untangle some of the knottier issues.” Not one to only swim in one lane, she also wrote about literature, psychoanalysis, crime, and biography.

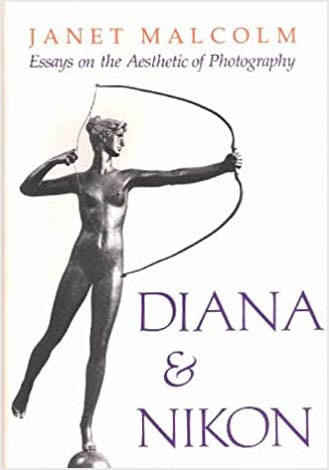

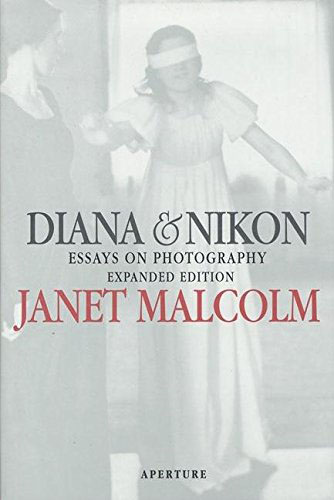

Malcolm’s first of 15 books was published in 1980. It collected 11 chronologically ordered essays and was titled Diana & Nikon: Essays on the Aesthetic of Photography. Publisher David Godine chose the name to provide separation from Sontag’s On Photography, although Malcolm didn’t like the title and “found [Sontag’s] interests remote from mine.” In either case, it wasn’t named for who you might think.

In 1997, Aperture released an expanded edition. They added a new preface, five essays, and more supporting images to the original material. It was titled Diana & Nikon: Essays on Photography and from now on I’ll just refer to this edition. The book was out of print when my interest in art criticism wagged its tail so I adopted a used copy from Better World Books and tried to give it as good a home as its first in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts Library.

For Malcolm, “the camera is simply not the supple and powerful instrument of description that the pen is.” But, unlike other photo criticism at the time, Diana & Nikon was liberally illustrated with 106 monochrome images, mostly photos, and a supportive bibliography. The original of one painting, Manet’s “The Execution of the Emperor Maximilian”, can be seen at BMFA. Tiny hand printing in my copy identified it as BM 30.444.

Malcolm’s essays opened with a statement, “that would propel the piece forward,” about a photographer or painter or writer’s work and would then segue to compare and contrast it with others always completing the circle back to photography. She discussed sainted masters and contemporary talent. Edward Steichen, Edward Weston, and Walker Evans are examples of the former, and Nancy Rexroth, Emmet Gowin, and Chauncey Hare of the latter. In all, she gave over 100 shout-outs to creatives. Half were new to me.

Malcolm’s essays hopscotched across 100 years of photography and dissected many of its key turning points.

- Stieglitz’s gifts and daring

- Weston’s dazzling abstracts

- Penn’s surprising portraits

- Avedon’s uncanny feel for the zeitgeist

- Szarkowski’s embrace of the snapshot

- Alexander and Hilsher’s clash of images

- Eggleston’s color

- Avedon’s journey to become the most celebrated fashion photographer

- Frank’s vision

- Stieglitz’s erotic O’Keeffe portraits

- Evans’ populism and Frank’s despair

- Galassi’s Before Photography exhibition

- Arbus’s not so identical sisters

- Bush’s home voyeurism

- Mann’s audacity and authority

- James and Bellocq’s delicately ironic exercises

“Two Roads” focused on iconoclast Robert Frank. He parlayed two Guggenheim grants into 27,000 exposures; cut down to 83 photos (0.3% if you’re counting) for The Americans, first published in France and later in the US. His images avoided pictorial values like “design, composition, tonal balance, lucidity, and print quality” and replaced them with “accidents, messiness, randomness, disorderliness, arbitrariness, blurriness and graininess.”

The book clearly revealed mid-century “America at its most depressing and pathetic.” Malcolm observed that “no one had ever made pictures like that before” and pointed to Arbus, Sonneman, and Callahan for support. Subsequently, there were just two polarized photography factions left; fine art and “action snapshots” with Frank becoming the Manet of the new genre. Modern critic Geoff Dyer, John Berger’s student, said “Photography would never be the same again.”

Written in two different periods and published without re-editing, Malcolm’s views evolved but still ring true. First delighted by pictorialism, only three years later almost accidental snapshots with surrealistic vitality were the thing. In another dozen years, valuing artists’ originality was the stand to take. Then, she constructed a sensitive and generous appraisal of where photography stood in relation to other arts. That alone encouraged photographers to do their thing, whatever it is. It’s also much more photographer-friendly than academic critics had been.

After 1997, Malcolm continued to occasionally muse about photography in the New Yorker and included five new essays in the 2013 collection Forty-One False Starts.

Malcolm spent months researching and writing each finely nuanced essay. Helen Garner said “she will not be read lazily” Active Reading helped sustain my effort to internalize this densely packed book and it might be a useful tool for you too.

This is my first go-around at reading photography criticism. I have little formal background but started with Barthes and Sontag anyway. The results were miserable. I couldn’t understand either. Benjamin was more accessible but dated. Last year, I learned that Janet Malcolm had ties to the New Yorker. I’m a big fan of E.B. White, so that resonated. They overlapped for about 10 years at the magazine and stylistically to a great extent. This book was a worthwhile challenge because of the high quality of her writing. This one is highly recommended — I think you’ll be delighted.

About the author: Jim Wilson is retired in Coastal Southern California. He enjoys wildlife photography and catching up on reading.