Amazon has responded to a letter of inquiry it received from U.S. Senator Chris Coons (D-DE) that asks the company to detail what happens to customers’ Alexa voice records and data after they speak to their virtual assistant. The Senator’s letter was prompted by a CNET investigation in May, which found that Amazon keeps voice records unless users manually delete them — and that it may keep text transcripts of those voice recordings indefinitely.

In Amazon’s response, published today on Senator Coons’ website, the company confirmed CNET’s findings, explaining that it does, in fact, store users’ voice recordings up until the point they choose to manually delete them.

In other words, the recordings are not automatically deleted at any point.

However, the original CNET report claimed text transcripts of the voice records were still maintained on Amazon’s servers even after users deleted their recordings, with “no option for you to delete them.” As CNET explained, Amazon would delete the text log from Alexa’s “main system,” but not remaining subsystems.

In Amazon’s response to the Senator’s inquiry, the company detailed what exactly it stores and what it does not.

It clarified that transcripts themselves are deleted when a customer chooses to delete a voice recording using the Alexa Privacy Hub dashboard. But, like CNET had claimed, the transcripts are deleted from Alexa’s “primary storage systems.” Amazon isn’t clear about where else they may still reside, saying only that there’s “an ongoing effort” to ensure the transcripts aren’t saved in any other Alexa storage systems.

It clarified that transcripts themselves are deleted when a customer chooses to delete a voice recording using the Alexa Privacy Hub dashboard. But, like CNET had claimed, the transcripts are deleted from Alexa’s “primary storage systems.” Amazon isn’t clear about where else they may still reside, saying only that there’s “an ongoing effort” to ensure the transcripts aren’t saved in any other Alexa storage systems.

Other data may also be retained after voice recordings are deleted, but it’s of less concern.

“We do not store the audio of Alexa’s response,” Amazon also noted. “However, we may still retain other records of the customers’ Alexa interactions, including records of actions Alexa took in response to the customer’s request,” the company said.

These records of actions may be retained by either Amazon or a third-party developer when an Alexa skill (voice app) is involved.

“For example, for many types of Alexa requests — such as when a customer subscribes to Amazon Music Unlimited, places an Amazon Fresh order, requests a car from Uber or Lyft, orders a pizza from Domino’s, or makes an in-skill purchase of premium digital content — Amazon and/or the applicable skill developer obviously need to keep a record of the transaction.”

This seems practical. After all, if you order an Uber or a pizza, or started a subscription, you’d expect there to be a record of that with the company where the order was placed. And no one really asks their pizza place to wipe their pizza ordering history.

Amazon also said that for other types of requests — like setting a recurring alarm, asking Alexa to remind you of something, putting a meeting on your calendar or messaging a friend — customers would not expect deletion of the voice recording or the data, nor would they want that, as it could prevent Alexa from performing the task.

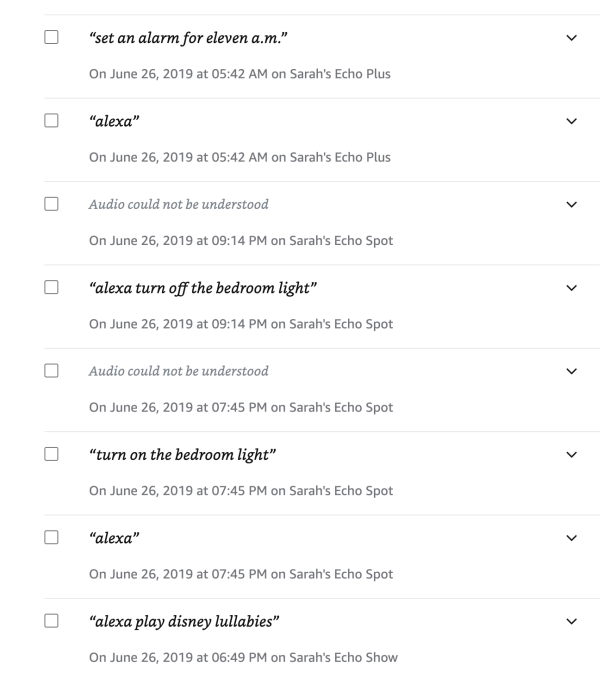

The company explained why it uses transcripts, saying that it helps to train and improve Alexa’s machine learning systems, and to provide a log to customers directly of what they said, what Alexa heard and how the virtual assistant responded.

Additionally, Amazon confirmed the system stops recording as soon as the customer stops speaking — as indicated by the blue light on the Echo device or, optionally, a tone that can be set to play.

The company then goes into more technical detail about the short buffer on the device, which is continuously overwritten, and says that Alexa is designed to record and process as little audio from customers as possible as processing audio not intended for Alexa would be costly and of no value to Amazon.

The original inquiry from the Senator gave Amazon a June 30 deadline, and the response letter was dated June 28.

Coons today applauded the timeliness of the response, but said there were still questions.

“I appreciate that Amazon responded promptly to my concerns, and I’m encouraged that their answers demonstrate an understanding of the importance of and a commitment to protecting users’ personal information,” he said, in a statement published to his website.

“However, Amazon’s response leaves open the possibility that transcripts of user voice interactions with Alexa are not deleted from all of Amazon’s servers, even after a user has deleted a recording of his or her voice. What’s more, the extent to which this data is shared with third parties, and how those third parties use and control that information, is still unclear. The American people deserve to understand how their personal data is being used by tech companies, and I will continue to work with both consumers and companies to identify how to best protect Americans’ personal information,” he added.

While many companies retain user data indefinitely, the increased focus on consumer privacy as regulators investigate big tech is starting to drive change. For example, last week Google rolled out a new feature that lets consumers configure their account settings to automatically delete location history on iOS and Android. But this is after years of hoovering up user data, and still requires manual action.

Still, many would argue that voice assistants should at least offer a similar setting: a way to set voice data to auto-delete, instead of having to remember to do so manually.

It’s worth pointing out that Amazon is not alone in hoarding user voice data.

Google also saves voice and audio clips to users’ accounts with an option to review and delete recordings. While saving data is its default, it does allow users to turn voice and audio activity off, if they prefer. Apple, meanwhile, saves Siri voice recordings for six months, then saves a copy of the data in a more anonymized fashion for up to two years longer.

But more broadly, there are concerns around Amazon’s review process itself and its lack of attention to user privacy.

As Bloomberg recently found, Amazon workers and contractors during the review process had access to the recordings, as well as an account number, the user’s first name and the device’s serial number. And they were also found to have been sharing audio clips in internal company chat rooms — either to get help with transcribing or to have a laugh at a funny recording.

In other words, there’s not a culture of privacy at Amazon when it comes to how a company should respect consumer’s private data. That’s different from Apple’s stance these days, where it aims to balance its need for some data retention with consumers’ desire for increased privacy.

In light of most big tech companies’ inability to properly self-police, there will ultimately be regulations put into place, as these companies insert themselves ever further into our lives. Now, they’re no longer just collecting data as we type into a keyboard or as we move around the world with a phone; they’re in our homes, listening to us and our children as we talk to their systems directly.

Amazon was asked for further comment regarding Coons’ statement.