Update: Twitter’s response has been added to the end of this post.

A new study by Amnesty International and Element AI attempts to put numbers to a problem many women already know about: that Twitter is a cesspool of harassment and abuse. Conducted with the help of 6,500 volunteers, the study, billed by Amnesty International as “the largest ever” into online abuse against women, used machine-learning software from Element AI to analyze tweets sent to a sample of 778 women politicians and journalists during 2017. It found that 7.1%, or 1.1 million, of those tweets were either “problematic” or “abusive,” which Amnesty International said amounts to one abusive tweet sent every 30 seconds.

On an interactive website breaking down the study’s methodology and results, the human rights advocacy group said many women either censor what they post, limit their interactions on Twitter, or just quit the platform altogether: “At a watershed moment when women around the world are using their collective power to amplify their voices through social media platforms, Twitter’s failure to consistently and transparently enforce its own community standards to tackle violence and abuse means that women are being pushed backwards towards a culture of silence.”

Amnesty International, which has been researching abuse against women on Twitter for the past two years, signed up 6,500 volunteers for what it refers to as the “Troll Patrol” after releasing a report earlier this year that described Twitter as a “toxic” place for women.

In total, the volunteers analyzed 288,000 tweets sent between January to December 2017 to the 778 women studied, who included politicians and journalists across the political spectrum from the United Kingdom and United States. Politicians included members of the U.K. Parliament and the U.S. Congress, while journalists represented a diverse group of publications including The Daily Mail, The New York Times, Guardian, The Sun, gal-dem, Pink News, and Breitbart.

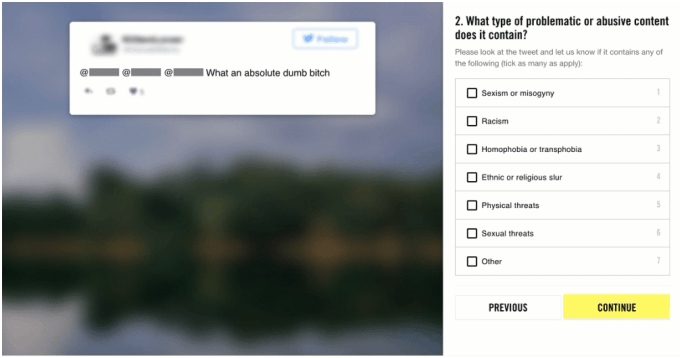

The Troll Patrol’s volunteers, who come from 150 countries and range in age from 18 to 70 years old, received training about constitutes a problematic or abusive tweet. Then they were shown anonymized tweets mentioning one of the 778 women and asked if the tweets were problematic or abusive. Each tweet was shown to several volunteers. In addition, Amnesty International said “three experts on violence and abuse against women” also categorized a sample of 1,000 tweets to “ensure we were able to assess the quality of the tweets labelled by our digital volunteers.”

The study defined “problematic” as tweets “that contain hurtful or hostile content, especially if repeated to an individual on multiple occasions, but do not necessarily meet the threshold of abuse,” while “abusive” meant tweets “that violate Twitter’s own rules and include content that promote violence against or threats of people based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, religious affiliation, age, disability, or serious disease.”

Then a subset of the labelled tweets was processed using Element AI’s machine-learning software to extrapolate the analysis to the total 14.5 million tweets that mentioned the 778 women during 2017. (Since tweets weren’t collected for the study until March 2018, Amnesty International notes that the scale of abuse was likely even higher because some abusive tweets may have been deleted or made by accounts that were suspended or disabled). Element AI’s extrapolation produced the finding that 7.1% of tweets sent to the women were problematic or abusive, amounting to 1.1 million tweets in 2017.

Black, Asian, Latinx, and mixed race women were 34% more likely to be mentioned in problematic or abusive tweets than white women. Black women in particular were especially vulnerable: they were 84% more likely than white women to be mentioned in problematic or abusive tweets. One in 10 tweets mentioning black women in the study sample was problematic or abusive, compared to one in 15 for white women.

“We found that, although abuse is targeted at women across the political spectrum, women of color were much more likely to be impacted, and black women are disproportionately targeted. Twitter’s failure to crack down on this problem means it is contributing to the silencing of already marginalized voices,” said Milena Marin, Amnesty International’s senior advisor for tactical research, in the statement.

Breaking down the results by profession, the study found that 7% of tweets that mentioned the 454 journalists in the study were either problematic or abusive. The 324 politicians surveyed were targeted at a similar rate, with 7.12% of tweets that mentioned them problematic or abusive.

Of course, findings from a sample of 778 journalists and politicians in the U.K. and U.S. is difficult to extrapolate to other professions, countries, or the general population. The study’s findings are important, however, because many politicians and journalists need to use social media in order to do their jobs effectively. Women, and especially women of color, are underrepresented in both professions, and many stay on Twitter simply to make a statement about visibility, even though it means dealing with constant harassment and abuse. Furthermore, Twitter’s API changes means many third-party anti-bullying tools no longer work, as technology journalist Sarah Jeong noted on her own Twitter profile, and the platform has yet to come up with tools that replicate their functionality.

For a long time I used blocktogether to automatically block accounts younger than 7 days and accounts with fewer than 15 followers. After Twitter’s API changes, that option is no longer available to me.

— sarah jeong (@sarahjeong) December 18, 2018

A friend coded up a way for me to automatically mute people who tweeted certain trigger words for me. (Like, say, “gook.”) This is also no longer available to me because of API changes.

— sarah jeong (@sarahjeong) December 18, 2018

Amnesty International’s other research about abusive behavior towards women on Twitter includes a 2017 online poll of women in 8 countries, and an analysis of abuse faced by female members of Parliament before the UK’s 2017 snap election. The organization said the Troll Patrol isn’t about “policing Twitter or forcing it to remove content.” Instead, the organization wants the platform to be more transparent, especially about how the machine-learning algorithms it uses to detect abuse.

Because the largest social media platforms now rely on machine learning to scale their anti-abuse monitoring, Element AI also used the study’s data to develop a machine-learning model that automatically detects abusive tweets. For the next three weeks, the model will be available to test on Amnesty International’s website in order to “demonstrate the potential and current limitations of AI technology.” These limitations mean social media platforms need to fine-tune their algorithms very carefully in order to detect abusive content without also flagging legitimate speech.

“These trade-offs are value-based judgements with serious implications for freedom of expression and other human rights online,” the organization said, adding that “as it stands, automation may have a useful role to play in assessing trends or flagging content for human review, but it should, at best, be used to assist trained moderators, and certainly should not replace them.”

TechCrunch has contacted Twitter for comment. Twitter replied with several quotes from a formal response issued to Amnesty International on December 12, Vijaya Gadde, Twitter’s legal, policy, and trust and safety global lead.

“Twitter has publicly committed to improving the collective health, openness, and civility of public conversation on our service. Twitter’s health is measured by how we help encourage more healthy debate, conversations, and critical thinking. Conversely, abuse, malicious automation, and manipulation detract from the health of Twitter. We are committed to holding ourselves publicly accountable towards progress in this regard. ”

“Twitter uses a combination of machine learning and human review to adjudicate abuse reports and whether they violate our rules. Context matters when evaluating abusive behavior and determining appropriate enforcement actions. Factors we may take into consideration include, but are not limited to whether: the behavior is targeted at an individual or group of people; the report has been filed by the target of the abuse or a bystander; and the behavior is newsworthy and in the legitimate public interest. Twitter subsequently provides follow-up notifications to the individual that reports the abuse. We also provide recommendations for additional actions that the individual can take to improve his or her Twitter experience, for example using the block or mute feature. ”

“With regard to your forthcoming report, I would note that the concept of “problematic” content for the purposes of classifying content is one that warrants further discussion. It is unclear how you have defined or categorised such content, or if you are suggesting it should be removed from Twitter. We work hard to build globally enforceable rules and have begun consulting the public as part of the process – a new approach within the industry. ”

“As numerous civil society groups have highlighted, it is important for companies to carefully define the scope of their policies for purposes of users being clear what content is and is not permitted. We would welcome further discussion about how you have defined “problematic” as part of this research in accordance with the need to protect free expression and ensure policies are clearly and narrowly drafted.”