The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 paved the way for decades of incremental changes to the way buildings, businesses and laws accommodate people with a wide variety of disabilities. At 30 years old this week, the law’s effect on tech has been profound, but there’s still a lot of work to do.

The ADA originally applied mainly to things like buildings and government resources, but over the years (and with improvements and amendments) came to be much broader than that. As home computers, the web and eventually apps became popular, they too became subject to ADA requirements — though to what extent is still a matter under debate.

I asked a few prominent companies and advocacy organizations what they think about how tech has improved the everyday lives of people with disabilities, and where it has so far fallen short.

Those who responded had the most to say about how tech has helped, of course, but also offered suggestions (and recriminations) for an industry that has in some ways only recently begun to truly include people with disabilities in its processes — and in many ways has yet to do so.

Claire Stanley, Advocacy and Outreach Specialist at the American Council for the Blind

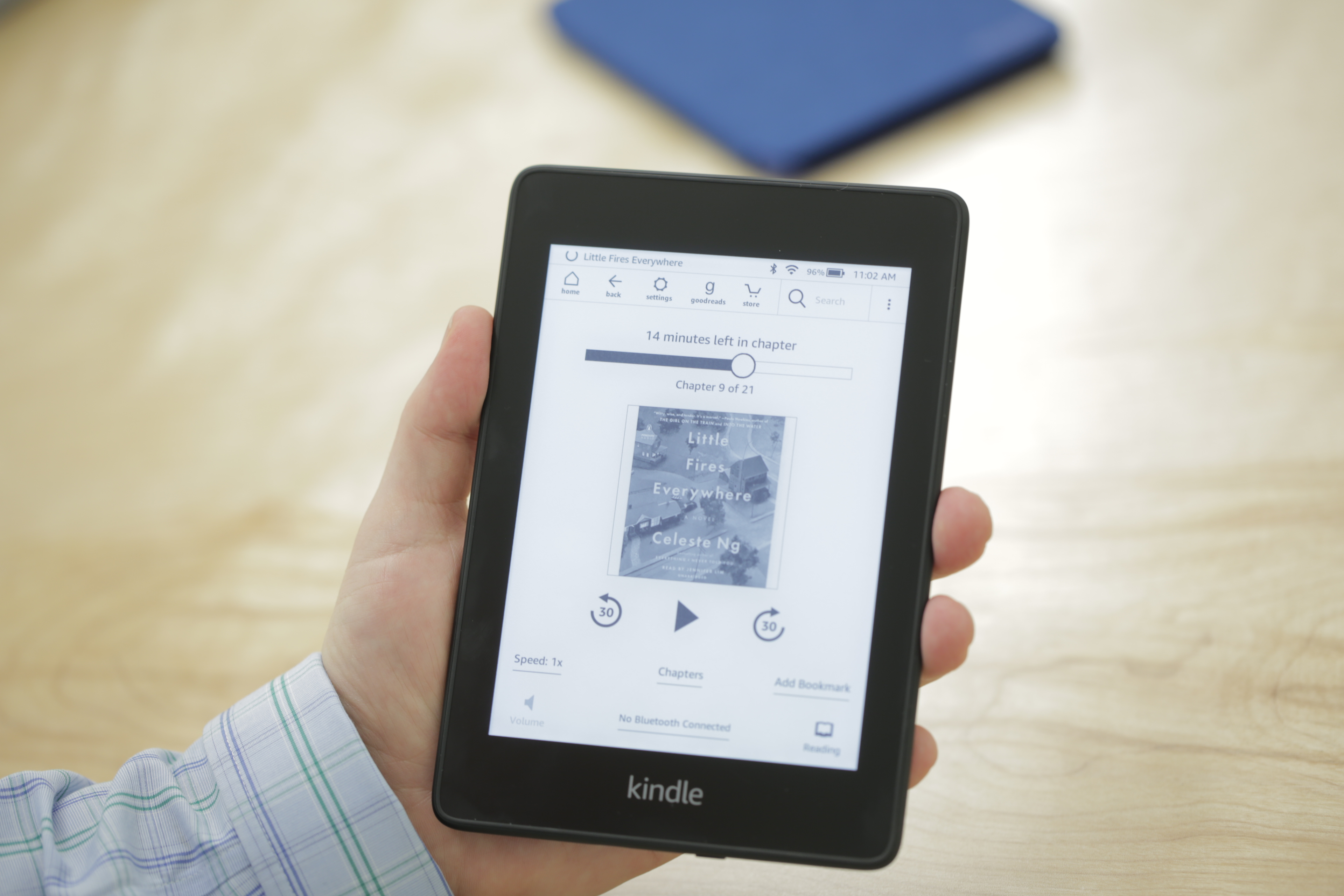

“Tech has opened the door to so many things,” said Stanley. “Books, for instance — 10 years ago to get a book you might have to wait for the Library of Congress to convert it to audio. Now, because of Kindles and e-readers, the day a book comes out I can buy it. Access is a lot faster than it once was.”

“The ability to do certain things in the workplace, too. The caveat is, people don’t always design software to work with accessibility technology. Designing with screen readers in mind can be very helpful, but if they don’t, that opens up whole new problems,” she said.

“Companies just don’t think about accessibility, so they design a product that’s totally inaccessible to screen readers. To my understanding, if you design it right from the get-go it should be easy to make it compatible. There are the WCAG standards — if programmers took even a cursory glance at these, they’d be like, ‘oh I get it!,’ ” said Stanley. “And I’ve heard from a lot of people that when you make something accessible to the blind it makes it better for everybody.”

That’s exactly the problem that Fable intends to alleviate by providing software testers with various disabilities as a service to companies that may not have thought that far ahead in their QA process.

New devices and services are also changing the landscape for blind folks.

“Braille literacy is going down because people are turning to audio synthesizers — but new designs of braille readers are coming out, and they’re getting cheaper. I have mine right next to me,” said Stanley.

Of course for the deaf-blind community braille is still indispensable. One dad hoping to teach his daughter braille recently built his own inexpensive braille education device — not something you were likely to do 20 years ago.

“And Aira is an app that has been around for about four years — basically, through video from your phone, a person on the other end can answer questions and identify things. I use it all the time. They’re starting to integrate AI to do some simple things like read signs,” Stanley said.

“We’ve also been working a lot in the autonomous vehicle space. That will open up a lot of doors, and not just for blind people, but people with other disabilities, the elderly, children,” she added. “I know we have a long way to go, but we’ve been fortunate enough to be at the table with companies and Congress when we’re talking about what making an autonomous vehicle accessible looks like.”

Eve Andersson, Director of Accessibility at Google

“To me, one of the most notable tech advances has been changes in captioning technology. About two years after I started at Google, in 2009, we introduced automatic captioning on YouTube using AI. Then eight years later, we introduced the ability to caption sound effects (laughter, music, applause, etc.) to make video content even more accessible,” said Andersson.

She pointed out that although captions were originally made with accessibility for deaf and hard of hearing users, they quickly became helpful for many other users who wanted to be able to watch videos on mute, in other languages and so on.

“Programming computers to be able to understand and display or translate language is allowing for so many more advances that benefit everyone. For example, speech recognition and voice assistants have made it possible to have the speech to text features that we have today, like voice typing in Google Docs or dictation in Chrome OS,” she said.

Live transcribe is another feature that tech has enabled, letting hearing impaired people follow in-person communications live.

“Before the ADA, some parts of the physical world remained inaccessible to people who are blind or low-vision,” Andersson said. “Today, you can find braille under almost all signs in the United States, which paved the way for us to create products like Google BrailleBack and the TalkBack braille keyboard, which both allow braille users to gain the information they need and communicate effectively with the world around them. In addition, the spirit of ADA in making the physical world accessible to people with disabilities is what inspired innovations like Lookout, an app that helps people who are blind or low-vision identify the world around them.”

“One area that we’re thinking about more and more is how to leverage technology to be more helpful for people with cognitive disabilities. This is an incredibly diverse space spanning many different needs, but it remains largely unexplored,” she said. “Action blocks” in Android are an early effort to address it, simplifying multi-step processes into single buttons. But the team is looking into larger scale improvements to help out those who have trouble using a smart device out of the box.

“As an industry, we need to work to ensure that people with disabilities — from employees to consultants to users — are always included in the process of developing a product, research area or initiative from the very beginning,” she said. “People with disabilities or who have family members with disabilities on my team bring their experiences to the table and we make better products as a result.”

Sarah Herrlinger, Director of Global Accessibility Policy at Apple

“It’s fundamentally about culture,” said Herrlinger. “From the beginning Apple has always believed accessibility is a human right and this core value is still evident in everything we design today.”

Though somewhat general of a statement, Apple has the history to back it up. The company has famously been ahead of others on the accessibility curve for decades. TechCrunch columnist Steve Aquino has documented these efforts over the years, summing many up in this feature.

Image Credits: Apple

The iPhone, being Apple’s flagship product since its introduction, has also been its main platform for accessibility.

“The historical impact of iPhone as a mainstream consumer product is well documented. What is less understood though is how life changing iPhone and our other products have been for disability communities,” said Herrlinger. “Over time iPhone has become the most powerful and popular assistive device ever. It broke the mold of previous thinking because it showed accessibility could in fact be seamlessly built into a device that all people can use universally.”

The feature that has been helpful to the most people is likely VoiceOver, which intelligently reads off the contents of the screen in a way that allows blind users to navigate the OS easily. One such user posted her experience recently, racking up millions of views:

As for where the tech industry has room to grow, Herrlinger said: “Representation and inclusion are critical. We believe in the mantra of many within disability communities: ‘Nothing about us without us.’ We started a dedicated accessibility team in 1985, but like all things on inclusion — accessibility should be everyone’s job at Apple.”

Melissa Malzkuhn, Founder & Creative Director, Motion Light Lab at Gallaudet University

“If not for the laws in place to safeguard our access, no one would implement them,” Malzkuhn said frankly. “The ADA really helped push greater access, but we also saw a lot of change in how people think, and what is considered socially responsible. More and more people now see that their use of social media comes with a sense of social responsibility to make their posts accessible. We would like to see that social accountability with all individuals, and with all companies, big and small.”

Gallaudet is a university that aims to be “barrier-free for deaf and hard of hearing students,” providing a huge amount of resources and instruction for that community. Many of the technologies its staff has used for years have seen major improvements as mainstream users have flocked to virtual meetings and the like and found them wanting.

Image Credits: Microsoft

“We have more video meeting options than ever, and they continue to improve. We also have seen a constant improvement in our experience with video relay services,” Malzkuhn said. She also cited voice-to-text as having improved a lot and provided serious utility; Gallaudet’s Technology Access Program has worked with Google’s Live Transcribe.

“Language-mapping processing, and the early pioneering work on gesture and sign recognition is exciting,” she added, though the latter is still a ways from practical use. She was unsparing in her criticism of the many attempts at smart gloves, however: “Enough with the sign language gloves. It reinforces a bigger ideology: Give deaf people something to wear and our communication issues will go away. It is not about putting the burden of communication on one group of people.”

“I would say that the Apple iPad has revolutionized how we look at the experience of reading for deaf children. In the Motion Light Lab here at Gallaudet University, we have created bilingual storybook apps, intersecting both ASL videos and written text on the same interface,” she said. “But technology will never replace the humanity in all of us. All it takes are attitudes and the willingness to communicate, regardless of technology. Learning a bit of sign language goes a long way.”

Malzkuhn emphasized the value of inclusion and chastised companies that fail to take even elementary steps in hiring and process.

“Companies that hire deaf people have it right. Companies that focus on inclusive design and accessibility as an important and ‘non-negotiable’ aspect in product design also have it right. Their products are invariably superior to inaccessible products,” she said, while those who do not are guilty of “a serious omission. Many companies strive to create products to ‘help’ our lives, but if we are not in the room in the first place, and if we do not have a seat at the table, that is not helpful. Inclusive design starts with an inclusive team.”

Investors need to look at startups focused on accessibility and deafness as well. Like any growing community, they need funding and mentorship.

Malzkuhn also wanted to make sure that companies are thinking about the deaf and hard of hearing not just as consumers of an end product, but full-fledged users.

“That is a driving force in my work — we need to always give tools so anyone can design technology. We need to ensure that we have the responsibility of training, teaching and making those accessible so we develop and cultivate the next generation of young deaf people who design and construct, who are architects of systems, who can program systems, as well as being end users of technology.”

Jenny Lay-Flurrie, Chief Accessibility Officer at Microsoft

“On a personal level, the ADA drove a new bar of awareness and provision of captioning, interpreting which are both invaluable to me in the workplace, home and navigating crucial life needs like medical care,” said Lay-Flurrie. “Technology can unlock solutions that can help empower people with disabilities in the spirit of the ADA and lead to greater innovations for everyone. To enable transformative change accessibility needs to be a priority.”

Like Google’s Eve Andersson, Lay-Flurrie highlighted captioning as a major recent advance.

“Captioning, like many other aspects of accessibility, is increasingly woven into the fabric of what we do,” she said. “Captioning has evolved so much in the last 30 years, and accelerated as a result of AI and ML in the last five. Teams now has AI captioning integrated and we have seen the impact of that during COVID with Teams Captioning usage up 30x from a few months prior.”

“Accessibility has also diversified — with technologies like Seeing AI, Learning Tool, and the Xbox Adaptive Controller as Microsoft focuses on inclusive design, building with and for people with disabilities in these instances, creating breakthrough technologies for blind/low vision, dyslexia and mobility,” she said.

The Adaptive Controller was one of the best hardware surprises of recent years — a device for playing games and interacting with computers and consoles that’s hyper-compatible and clearly the result of immense effort and expenditure.

It’s an example of one of the “doors that remain closed and need to be opened, vehemently and with speed,” as Lay-Flurrie put it. “Seeing AI is a great lens on what is possible here, and I get excited to think about what AI/ML, as well as ARm can do across the spectrum of disability. Additionally, we believe that AI can help unlock solutions to some of the biggest challenges people with disabilities face, which is why the AI for Accessibility program plays a crucial role in how Microsoft is working to drive inclusive innovation.”

Lay-Flurrie had a good deal to say on how to integrate inclusivity into a company’s processes — and with good reason, seeing as Microsoft has been a leader on these issues for years.

“Accessibility isn’t optional. It must be part of your business, ecosystem and managed/measured,” she said. “It starts with people and we have really focused on how we build an inclusive culture, pipeline of talent. Though we are still continuing to grow and learn, we have also taken steps to share our learnings with other organizations through resources like the Autism Hiring Playbook, Accessibility at a Glance training resources, the Supported Employment Program Toolkit and the Inclusive Design Toolkit.”

“We realize that each organization has its own pace and starting point. The first step is to recognize the need to design for accessibility,” she continued. “It’s particularly important to evaluate the maturity of a product development life cycle through the lens of accessibility and look to build in assistive features from the start, not bolted on later in the process. But there is more to do here. Until then, my mantra stands — if you don’t know it’s accessible, it’s not.”

Mike Shebanek, Head of Accessibility at Facebook

“The portability, ease of use, affordability and built-in accessibility of smartphones has allowed people with disabilities to be more connected, more mobile and more independent than anyone thought possible 30 years ago,” said Shebanek. “The rise of voice technologies like speech synthesis, speech recognition and voice control of devices has also radically improved the lives of people with disabilities.”

“Facebook created React Native, and made it open source, so that developers can create accessible mobile apps. We’ve also helped set global digital standards for web accessibility that enable everyone to enjoy a more accessible internet,” he continued.

Like the others, he suggests that tech companies need to consider accessibility needs and methods early on, and increase the numbers of people with disabilities in the development and testing process.

Machine learning is helping address some major obstacles in a more automated way: “We’re using it at Facebook to power automatic video captioning and create automatic Alt-Text to provide spoken descriptions of photographs to people who are blind,” said Shebanek. “But these are only recent innovations and the industry has barely begun to scratch the service of what’s possible in the next 30 years as we begin to thoughtfully address the needs of people with disabilities.”