Droughts, climate change and deforestation are putting forests at risk worldwide, so studying these ecosystems closely is more important than ever — but it’s a hell of a lot of work to climb every tree in the Sierra Nevada. Drones and advanced imaging, however, present an increasingly practical alternative to that, as this UC Berkeley project shows.

Todd Dawson, an ecologist at the university, spends a lot of time up in trees, measuring limbs, checking growth and so on. As you can imagine, it’s slow, dangerous and demanding work — which is why a collaboration with drone maker Parrot and imaging tech company Pix4D was appealing.

“Before, a team of five to seven people would climb and spend a week or more in one tree mapping it all around. With a drone, we could do that with a two-minute flight. We can map the leaf area by circling the tree, then do some camera work inside the canopy, and we have the whole tree in a day,” Dawson said in a Berkeley news release.

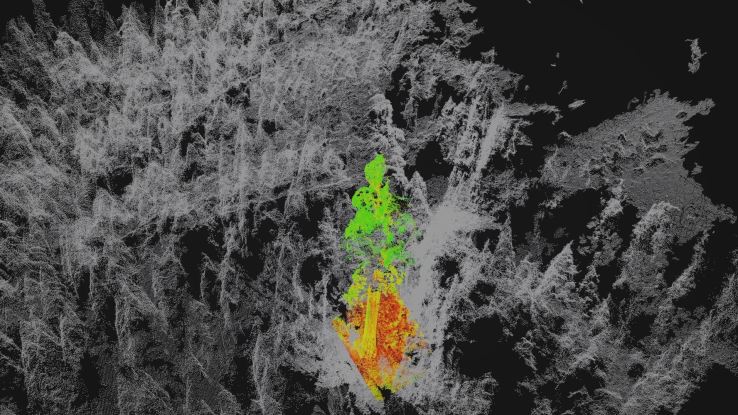

Drones are, of course, commonly used in forestry and agriculture, but this particular setup is very focused on quickly and repeatedly profiling individual trees. Pix4D’s “Sequoia” camera collects light in a variety of complementary wavelengths — a useful technique called multispectral imaging — while also building a detailed 3D point cloud using LIDAR. Between the two, the resulting data can show overall health and growth; it can also be collected repeatedly over weeks or months, creating a time-lapse view.

Processing and storing the data is becoming less troublesome as well; Pix4D created software to quickly turn around the data and make it accessible for this particular purpose. All that data can feed into prediction models for other things: overall leaf area can help predict carbon exchange, and growth or health patterns can be mapped to climatic or anthropological ones.

Dawson’s project was a pilot; Parrot and Pix4D are also launching a “Climate innovation grant” through which researchers can get access to drones and imaging hardware — any topic “from archaeology to zoology,” as long as it will “foster innovation in understanding and mitigating the impacts of climate change.”