There is a secret behind every open office in Silicon Valley — and it isn’t the drain on productivity.

Tech companies have been the vanguards for pushing corporate culture forward toward “radical transparency.” Mark Zuckerberg works in a fully transparent four-walled glass office surrounded by the rest of Facebook. Valve got rid of managers and titles so everyone can be their own boss. Startup founders host weekly town halls, Friday all-hands, and AMAs. Companies go to painstaking lengths to signal that they trust their employees – to show that this is your company.

But while your company might adopt an open floor plan and give out free snacks so you can feel closer to your coworkers, they likely don’t want you knowing how much they make, who is affected by the impending layoffs, or whether executives are making the right decisions.

The open office has never been more closed, and tech companies are no different than old corporate America in their authoritarian approach to controlling how their employees should think about issues that matter in the workplace. In fact, it may even be more insidious because it’s tucked away behind the veneer of a cheerful, open office.

This is what makes social network Blind so fascinating. Raw and unfiltered, Blind is the antithesis to HR’s utopic vision of a manageable and orderly corporate culture. Instead, it operates outside the walled gardens of IT with no rules and no official corporate supervision.

With Blind, users are completely anonymous, but are required to submit a verified work email to join a company channel. Inside, they are able to freely ask, discuss, prod, and complain without fear of retribution or judgment.

In short, it’s HR’s worst nightmare, and it’s wildly successful.

Building a compelling social product

Blind’s engagement numbers are staggering. It has over 2 million users, including 43K at Microsoft, 28K at Amazon, and 10K at Google. In South Korea, half of all employees at companies over 200 people are active monthly. The typical monthly active user logs in three to four times per day and spends 35 minutes using the app. At the height of the Susan Fowler scandal, Uber employees were spending almost 3 hours a day on Blind. All that, and the entire company is 38 people.

At the heart of Blind’s magic is something universal to every person who has ever been employed — the duality between our personal selves and our “work” selves, and the human drive to be both intimate and in control of our relationships. There is no place more difficult to navigate this duality than the workplace, where we want to feel loved and understood, but also respected.

Hierarchy, politics, and negative career impacts burden conversations about difficult topics, and so Blind tears these barriers down one employee at a time, affording a space for uninhibited dialogue. More importantly, Blind succeeds as a resource for questions not only company-related, but also around career, family, and life decisions.

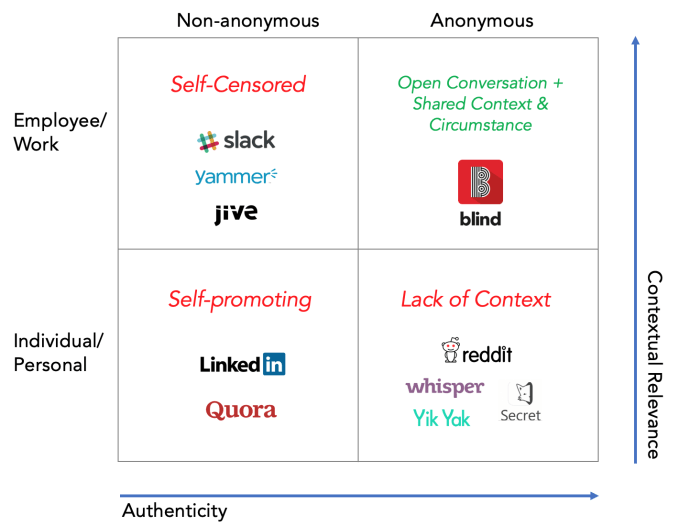

Blind is in many ways an evolution of a long lineage of ideas in social networking. It’s unique achievement is the recombination of these different ideas to create a platform that is both a safe space for free and open conversation (via anonymity), along with a vetted, contextually relevant community (via workplace email authentication).

Let’s walk though each of these categories to understand Blind’s success.

Lack of Context (Anonymous + Individual/Personal) – Companies like Yik Yak, Secret, and Whisper pioneered the anonymous social network on the consumer side. However, they were beleaguered by cyberbullying, and served more as a digital exhaust pipe for teenage angst and trolling. Perhaps the most successful semi-anonymous social network today is Reddit, where legions of loyal community members cover every topic imaginable. However, what all of these anonymous communities lack is the critical element of shared context and circumstance.

Put another way, your fellow community members on Reddit may share your interest in ice fishing, but they likely will not understand who you are. As Blind cofounder Kyum Kim puts it, “it’s hard for someone to complain on Reddit about feeling poor while making $200K a year without fear of backlash, but on Blind, your coworkers are in the same income bracket, and likely similar education levels, neighborhoods, etc. They can empathize with your situation.” On Blind, there is a single community (your workplace) that spans multiple topics, and there’s a baseline, tacit understanding of each other’s life circumstances, allowing for deeper conversations.

Self-Promoting (Non-Anonymous + Individual/Personal) – LinkedIn and Quora are useful professional platforms, but because individuals and brands are the stars of these platforms, posturing and self-promotion can be quite frequent. When you ask a question on Quora, you are submitting your inquiry to a body of self-proclaimed experts. While many responses can be genuine, the ultimate currency that drives the platform is credibility and brand building, which inhibit authentic and vulnerable conversations from occurring.

Self-Censored (Non-Anonymous + Employee/Work) – On the enterprise side, Yammer, Jive, and recently Slack have attempted to upgrade the creaky company intranet into the enterprise social network. While these tools might make it easier to connect to your coworkers, the conversations happening on these platforms are no different than before – ultimately, these tools are designed to get work done, not for questioning, debating, or reflecting on how work should be. Conversations about sensitive subjects (e.g. how to deal with a bad manager) are unlikely to happen on a non-anonymous, corporate-sanctioned platform where that same bad manager might well be watching.

Finally, we have Blind. The platform strikes a balance between the freedom of anonymity and the context of a shared workplace. The result is a forum for surprisingly rich, relevant, and authentic conversations. While company channels are accessible only to insiders, a look at Blind’s public site (where you still need a verified work email, but you can chat with anyone outside your company) reveals a flavor for the types of conversations that are possible. An engineer at Amazon recently posted about how to deal with a mid-life crisis, with 42 responses of encouragement and advice. Another employee moving from India has a wife suffering from depression and is seeking help navigating the US healthcare system.

It turns out that where we work is a good proxy for who we are, and our coworkers have been an untapped community of wisdom.

Trust and safety

Catalin205 via Getty Images

Blind is by no means perfect. Like all online platforms and particularly anonymous ones, it invites its share of trolls. One look at the “Relationships” section on Blind’s public site and you’ll find questions about how to deal with one-night stands with coworkers and a poll asking guys how many girls they’ve slept with before marriage. While these questions could certainly have come from a genuine place, they are easy fodder for trolls, and the ensuing conversations can be alienating and provide an unnecessary megaphone for toxic bro culture.

Blind acknowledges that these issues exist, but claim that they happen less frequently inside company channels. Because users authenticate with their work emails, cofounders Sunguk and Kim believe that Blind users feel a greater sense of responsibility to each other because they are engaging a real community with shared context and goals.

The vast terrain of cyberspace might suffer from the tragedy of the commons and moral hazard, but within your workplace channel on Blind, your digital community maps onto a physical community – even though you are anonymous. This is evidenced by the successful self-policing on the platform, where 0.5% of all posts have been removed (higher than average for a social media platform), and all of these originated from user-generated flags.

A More Perfect Union

Blind’s success illuminates a reality that is often overlooked: corporations aren’t naturally democratic or transparent. While there are platforms to discuss our roles as individual working professionals (e.g. LinkedIn), there are very few places to gather and organize as employees of companies to collectively bargain for a better workplace.

This is by design. HR, the supposed watchdog of employee wellness, is neither elected nor truly representative, as they must balance the competing goals of being a third party resource for employees while also protecting the company against its employees.

Companies will always be incentivized to maintain an asymmetry of information. Friday all-hands and town halls are heavily scripted by companies. Rarely do we see anyone describing a healthy, transparent culture as a place where employees are freely conversing amongst themselves.

For companies with something to hide, the idea of a public square where conversations happen freely should be alarming. Blind has already been at the center of exposing two major scandals (e.g. the “nut rage” incident by a Korean Air executive and the news that Lyft was spying on its users.)

Blind picks up where labor unions left off and where HR has failed — to serve as a safeguard against corporate overreach, and to provide a protected space for employees to collaborate around solutions to improve the workplace.

A truly open office

For companies, Blind’s rise shouldn’t be seen as bad news. Blind can be a rich source of insight where HR software falls short. While employee engagement surveys have become popular in HR circles (and a crop of well-funded HR tech companies have consequently flooded the market), these practices suffer from the same issues of hosting a town hall. The company decides on the questions asked and interprets the answers given. With Blind, for the first time, HR and executives will have a pulse on employee sentiment that is both real-time and authentic. As Moon puts it, “no company is perfect, and if it was, Blind would not need to exist.”

In short, Blind understands more about your employees than anything in your HR stack.

Where does Blind go from here? Moon and Kyum believe they’re just getting started. Today, Blind is only available in the U.S. and South Korea, and it has been focused on tech companies. Their push into more traditional industries is showing some early signs of success with Johnson & Johnson, Dow Chemical, Barclays, and the US Navy coming online recently. There is still work to do in cleaning up different communities to ensure that conversations are inclusive and not alienating. And of course, Blind has to find a path to becoming a sustainable, revenue-generating company without compromising its integrity with users.

But one can only imagine the potential for Blind if it continues on its path upwards — the anonymous social network that understands who you are, the pulse survey that is authentic and real-time, and the first truly safe and open office made for employees, by employees.