2What’s in a name?

More than two years ago, Fast Company published a story with the headline “Two Ex-Googlers Want To Make Bodegas And Mom-And-Pop Corner Stores Obsolete.” The focus of the story was a nascent startup by the name of Bodega .

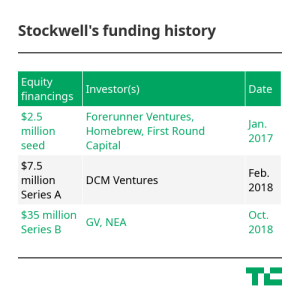

The company had raised $2.5 million in funding from First Round Capital’s Josh Kopelman, Forerunner Ventures’ Kirsten Green and Homebrew’s Hunter Walk. To announce their funding and vision to create the unmanned store of the future, Bodega briefed a number of journalists on its big idea. Given the simplicity of its product — a tech-enabled vending machine, in essence — the team was blindsided by the uproarious response that followed. September 13, 2017 was supposed to be the most exciting day in the startup’s history, at least until that point; instead, it was a nightmarish lesson in poor branding and messaging.

The press storm and public lambasting catapulted Bodega into the limelight — for all the wrong reasons. Overnight, the company went from just another early-stage commerce business to the symbol of everything that is wrong with Silicon Valley. Many wondered if it would fall victim to criticism and crumble like Juicero, a well-financed startup that sold a $400 juicer — that is, until a Bloomberg story proved its juice packets could be squeezed by hand, no machine necessary. Or would it take the public condemnation in stride, hearing out the critics and amending its brand as necessary?

Two years after its ill-fated launch, the latter seems to be true. Today, the three-year-old Oakland-based company — now known as Stockwell — is said to be growing quickly thanks to more than $45 million in venture capital funding from a number of deep-pocketed investors, the company has confirmed to TechCrunch.

Bodega’s original branding included a cat logo. Cats are often features of small neighborhood stores, known as bodegas.

Public outcry

“Bodega is either the worst named startup of the year, or the most devious,” wrote The Verge in the fall of 2017. “Tech firm markets glorified vending machines where users can buy groceries,” said The Guardian. The Washington Post dubbed the company “America’s most hated start-up.” CityLab, which writes about issues impacting cities, bluntly reported “Bodega, a Startup for Disrupting Bodegas, Is Terrible,” followed by 30 reasons why the startup sucks: “Maybe a Bodega can stock Soylent to appeal to people who also think that eating delicious food is a grim burden,” CityLab wrote. “Why do tech wizards keep thinking of new and more horrible ways to avoid dealing with people? How come they hate being human?”

It’s safe to say Bodega endured one of the most catastrophic company launches in the history of tech startups. But the press cycle surrounding Bodega was more than an attack on the startup alone. It represented a greater frustration with Silicon Valley culture and its reputation for funding “disruptive” products devoid of impact. Time and time again, VCs had proven their willingness to inject millions into standard concepts lacking originality. A juicer had raised more than $100 million, after all, scooters were beginning to attract private capital and Soylent, which sells a meal replacement drink fit for techies, was hot off the heels of a $50 million round.

A mini-fridge equipped with computer vision technology boasting a culturally insensitive name wasn’t going to change the world. Questioning why it had the support of VCs was only fair.

An innocent misunderstanding?

Behind the upsetting name was a business developing hundreds of five-foot-wide pantry boxes to be housed in luxury apartment lobbies, offices, college campuses, gyms and more. Similar to Amazon Go, the “smart stores” recognize what customers remove from the cases using computer vision and automatically charge the credit card associated with the account.

When you’re not in the room, the name of your company is what gets passed between people. -James Currier, NFX .

Bodega was founded by a pair of Google veterans, Paul McDonald and Ashwath Rajan. It had all the ingredients for a successful startup stew. Founders with years of experience in big tech: McDonald spent more than a decade at Google; Rajan had just finished up the search engine’s competitive associate product manager program. Both attended top universities: University of California -Berkeley and Columbia University, respectively. Still, neither of the two men nor their investors seemed to have predicted the controversy afoot.

“Bodega doesn’t want to disrupt the bodega,” Hunter Walk, a Bodega investor and co-founder of the seed fund Homebrew, wrote in a 2017 blog post. “Some instances of today’s press coverage suggested that element, a sound bite which, exacerbated by Bodega’s naming, pissed people off as another example of tech startups being at best tone-deaf, and at worst, predatory … It didn’t occur to me that some people would see the word and associate its use in this context with whitewashing or cultural appropriation.”

The company, too, quickly authored a blog post outlining their thought process behind the name: “Rather than disrespect to traditional corner stores — or worse yet, a threat — we intended only admiration,” McDonald wrote.

After penning blog posts, the founders continued working on the company under the provocative and upsetting name. Meanwhile, investors seemed unfazed by the negative press, evidenced by the company’s ability to continue raising venture capital funding. After all, many of the best businesses endure the wrath of bloggers, competing founders and the general public. As for VCs, high-risk bets are just part of the ball game.

DCM Ventures, a U.S.-based venture capital fund with offices in Beijing, Tokyo and Silicon Valley, was the first to agree to invest in Bodega following the PR disaster. The firm, an investor in Lime, Hims and SoFi, led a $7.5 million Series A financing in the business in early 2018, the company confirmed. DCM co-founder and general partner David Chao joined the company’s board following the deal. DCM vice president David Cheng is also actively involved with the company, according to his bio.

Finally, after pocketing nearly $10 million in total funding, Bodega announced a name change: “Did you buy something today from a Bodega?” Bodega’s McDonald wrote. “You may have noticed that we’ve changed our name to Stockwell . Our new name is one of the changes we’re making as we expand our offerings and open more stores around the country.”

Stockwell, fka Bodega, founders Paul McDonald (left) and Ashwath Rajan (Courtesy of Stockwell).

A new era

With a new logo and a toned-down, somewhat bland identity, Stockwell had a fresh start and, soon, more attention from top VCs. In late 2018, the company raised a $35 million round of funding co-led by Uber and Slack-backer GV, formerly known as Google Ventures, and NEA, an investor known for bets in Coursera, MasterClass and OpenDoor, Stockwell has confirmed. NEA’s Amit Mukherjee and GV’s John Lyman joined Stockwell’s board as part of the deal, which is said to have valued the business at north of $100 million. Stockwell, however, declined to confirm the figure.

Instead of announcing the news via TechCrunch, Venture Beat, Forbes or another tech publication, as is the norm for fast-growing consumer-facing startups, Stockwell remained mum on financing events and scaling plans, assumedly burned by the press and the public’s scorn a year prior.

Rather than subject itself to continued scrutiny as it attempted to rewrite its narrative, Stockwell was heads down, iterating, expanding and quietly raising millions. Bad press can break a startup, and given the sheer number of negative reports on Stockwell so early on, the company had already defied the odds. Keeping a low profile was undoubtedly the best strategy moving forward, and it seems to have paid off.

“It was a difficult time and transition and we learned a lot from it,” a spokesperson for Stockwell said in an email to TechCrunch. “As a company, we put our heads down and focused on building our business. We kept a low profile and concentrated on our core product, the mission, and the people who work for us. We’re excited for the progress we’ve made but won’t forget the path that got us here.”

Today the company counts 1,000 “stores” in the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Houston and Chicago. Stockwell has used its latest infusion of funding to explore shared ownership models, i.e. the opportunity for anyone to run their own Stockwell store. The company tells TechCrunch they are also working on building out their “unique curation model,” which allows customers to help determine what items are stocked in their local “store,” as well as their support for emerging brands, whose products they can stock in their next-generation vending machines.

Stockwell’s five-foot wide next-generation vending machine.

So what’s in a name?

Human beings make snap judgments, evaluate products quickly and can develop distaste for brands in a matter of seconds. A company’s moniker is their first opportunity to impress customers.

“When you’re not in the room, the name of your company is what gets passed between people,” writes NFX co-founder James Currier. “It speaks for you when you’re not there … It sets expectations of your company in the blink of an eye. And first impressions are hard to change. Both positive and negative.”

Most cases of poor startup naming are easily fixed. Most founders aren’t forced to bear the brunt of the internet’s fury. The case of Bodega is much more extreme and, as such, serves as the ultimate lesson for founders searching for the best way to tell their story. At the end of the day, avoiding a complete and total train-wreck is easy if you include a diverse group of people in the naming process and remember there’s a lot in a name — if that weren’t the case, Bodega would still be Bodega.