In 2012, we launched Thought Catalog Books. With Thought Catalog the website, we mastered producing short-form writing for the web and we wanted a new challenge. We hoped to build a counterweight to Thought Catalog’s trendy digital brand with a more contemplative spin-off brand as a book publisher.

There were two questions driving the identity of our book startup: In the age of algorithms and social media, can we create an enclave where creative and intellectual sophistication still matter? Can we build a publishing model where readers instead of advertisers are the main stakeholders?

It’s critical to understand Thought Catalog Books in the context of the website because when ThoughtCatalog.com went live in 2010, it wasn’t a viral publisher. The non-buzzworthy “Thought Catalog” name reveals a total lack of foresight into the viral publisher trend. Thought Catalog was supposed to be an “experimental cultural magazine.”

The problem was, the experiment with journalistic writing had a conclusive and dire result. Long-form writing like profiles of musicians, book reviews and cultural analysis would bankrupt us, and we pivoted. Audience insights from Facebook data become our publisher, Google data our editor in chief, and Twitter signals our managing editor. Thought Catalog was one of the first magazines built by data from social media and that made us, along with BuzzFeed and a few others, part of the first gold rush of digital publishing.

Money wasn’t the only goal, though. Money is a lifeblood for any company, but we still had higher ideals. We wanted readers, not just visitors; artistic appreciation, not just social likes. This desire to elevate the conversation is what separates a content company from a media company, and we consider ourselves the latter. Well-funded media companies deal with this by commissioning what is deemed the “important stuff” as a loss leader. As a bootstrapped startup, we never had the ability to have loss leaders. So a book imprint seemed like the way to go for two reasons:

-

The book business model is kinder to long-reads. A 5,000-word piece commissioned at $1.00 a word requires about one million reads for the publisher to break even on an optimized ad setup. Often even viral lists won’t get one million visitors, let alone long-form investigative journalism or in-depth creative work. With book publishing, you would only need about 2,000 people to buy the e-book at $4.99 to recoup your investment.

-

Books allowed us to commission expensive visual art projects. Web publishing didn’t just cut costs for writers, it also decimated the need for complex visual art to accompany pieces. In the visual world, a meme generated on a phone would often generate more readers and profit than a brilliant illustration from a premier artist. The economics of the web made doing this impossible, but when it came to book covers and packaging, we could justify the budget for amazing visual commissions because, despite the old cliché, people do judge books by their covers.

Books were the perfect platform: simple economics, a chance to impact visual and written creation and a market fit. What have we learned? It’s been five years, and these are the big-picture lessons.

The medium is indeed the message

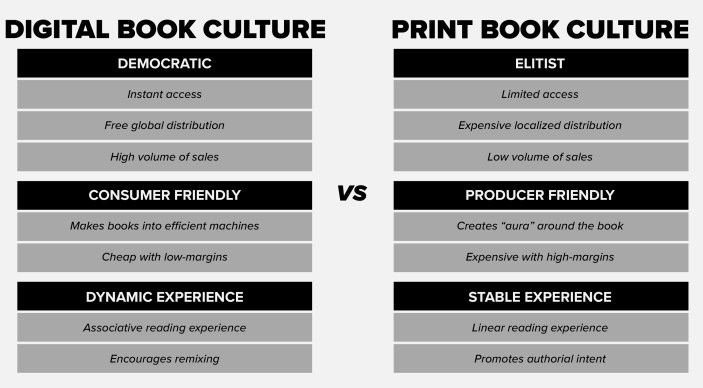

We were surprised to learn that print books and digital books were almost two distinct businesses with totally different operating models. While a print book and an e-book share identical content, they reflect diametrically opposed media formats. Print books are luxury goods and e-books are utility, and this has real implications in the strategy and workflow behind the marketing and production of each.

Here is how we think about the difference between the two formats.

This technical distinction is also present in consumer behavior. E-books — with their instant access and cheap prices — sell generally 6x more quantities than print books for us. That said, a print book will generally generate 7x more revenue than an e-book. It’s hard to generate revenue on an e-book because the whole premise of the platform is: I want this quickly and at the cheapest price possible. The premise of a print book in the digital age is driven by luxury: I read better on paper… or… I like the feeling of turning a page.

You can’t create much markup on utility, whereas you can create a great deal of markup on luxury. This has been perhaps one of the most important insights driving Thought Catalog Books’ growth. The print books department needs to be run like a luxury goods company, while the e-book department needs to be run like a technology company. The content is the same, but the medium dictates an entirely different business model.

There are surprising economic benefits to book publishing

It turned out that thoughtful advertisers love books and Thought Catalog Books has become a critical tool for the Thought Catalog sales team. Online native content is effective for short-form stories, but if a brand wants to cut deeper and build an in-depth story, the print book is the perfect medium. Native and sponsored content is short-form content that readers only engage with for a few minutes. With sponsored books, advertisers tap into an in-depth branding opportunity using the most time-tested storytelling technology out there — a printed book, where readers often spend hours if not days with their content and keep it perhaps forever on their bookshelf.

Aside from selling sponsored books to our clients, we’re excited to see significant revenue opportunities from audiobooks, an industry that is currently exploding. We also saw ample opportunity with good old-fashioned movie adaptations of our books.

Expensive commissions are still loss leaders, even in book publishing

The debate between commercial viability and artistic integrity is filled with thorns. The best words — from Homer to Shakespeare to Virginia Woolf to Jonathan Franzen — “sell” well right away. Classics are often classics instantly, particularly in the realm of fiction.

Nevertheless, there is important work to be done in philosophy, journalism, biography and other genres that may never be bestsellers but are just as important to society. Such stories are like elegant math problems that, while not applicable to a wide audience, are still useful to those who know how to approach them.

Supporting this kind of writing — such as Elizabeth Wurtzel’s media-theory tour de force Creatocracy, Simon Critchley’s heartbreaking critical survey of Suicide and Sabine Heinlein’s The Orphan Zoo, an invitation into the notorious Creedmoor Psychiatric Center in Queens — is priceless even if it exists outside of popular culture and market norms. With book publishing, we’ve found a way to better support this kind of work, allow writers to get paid and, while perhaps not make a profit, ensure the works reach the right people and are preserved in the respectful medium of the book.

Don’t fear Amazon

Amazon touches every aspect of the business so powerfully that it feels like a monopoly. Its power, however, is limited in three important ways.

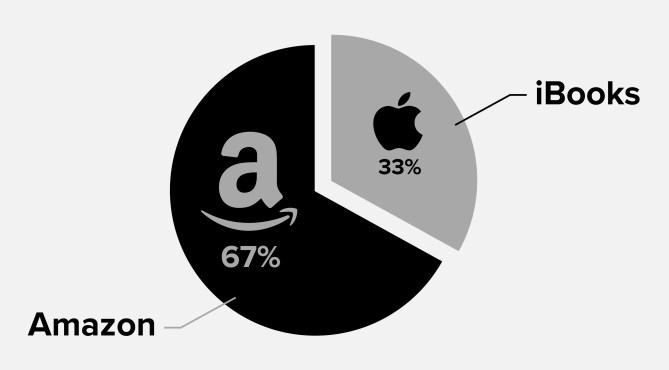

iBooks represents real competition with Amazon in the e-book market. A 2014 study by Publishing Technology reported that iBooks controlled 31 percent of the e-book market. This correlates with our 2016 data, where iBooks drove 33 percent of our e-book sales. Moreover, iBooks is likely to grow as people abandon traditional e-readers and use their phones or desktops — where Apple has an inherent advantage over Amazon — to read books.

The Big Four publishers are indispensable. Amazon has always had the dream of removing the “gatekeepers” and creating a direct relationship between authors and readers. However, ask any person what their favorite books are, and the odds of them being self-published are about as likely as their favorite TV show being a YouTube web series. The reality is that the creative and financial intermediary roles that major book publishers play are critical to the book industry, just as those roles are in the film or TV industries. The publisher’s role is here to stay.

As e-books become increasingly popular, selling physical books on Amazon might make less sense. At Thought Catalog Books, Amazon is a dream partner for digital distribution and certain kinds of print distribution. Amazon doesn’t make sense, though, for selling our premium print books. For us, there is more personality in ordering the book through a more custom e-commerce experience or through an independent brick-and-mortar retailer. If books are truly luxury items, then just as a high-end clothing brand doesn’t want to sell on Amazon, we, as a specialty book publisher, don’t want our products there either. This might eventually be the case with other, larger publishers at some point which, at the very least, may begin limiting their print distribution on Amazon.

The future of books is bright

“The lack of video, the lack of audio,” writes Richard Nash in What is the Business of Literature?, “is a feature of literature, not a bug.” This is exactly how we look at the book business at Thought Catalog. Books aren’t an antiquated technology. Books are cutting-edge technology. In fact, books are the greatest virtual reality machines on the market. While virtual reality gear like Oculus engulfs the brain to present a different reality, books engage the brain and present a different reality through a more creative exchange between medium and self.

This should be reassuring for publishers, and, while a book publishing company will never grow at the exponential speeds of Facebook or a traditional technology company, that’s their charm. It’s an industry about deep engagement, not quick growth.

Featured Image: Sue Clark/Flickr UNDER A CC BY 2.0 LICENSE