The Jetsons presented a highly entertaining vision of what homes of the future would look like. The animated television show anticipated a world where humans would be able to do everything with just the push of a button.

In many ways, the show turned out to be prophetic; today we have printable food, video chats, smartwatches and robots that help with housework — and flying cars may even be on the way. The challenge for companies is to integrate digital technologies in meaningful ways that enhance people’s homes and improve their lives.

Many of the innovations to emerge over the past few years have been geared toward this kind of “push-button living.” Thanks to the rise of smartphones and the proliferation of cheap sensors, it is possible to make just about any household appliance “smart” and “connected.” By 2019, companies are expected to ship 1.9 billion connected home devices, bringing in about $490 billion in revenue. However, we are already seeing that many of these connected home devices are limited in their utility and scope.

Take the example of a connected coffee maker. Pushing a button on your phone to turn on the coffee maker from bed may seem convenient, but coffee makers with built-in timers have existed for years, and making coffee once you are already up is just not that much of a pain point. Are consumers really going to buy a new coffee maker and download a new app for such a minor “improvement?” The same is true for lighting. Flipping a light switch is less cumbersome than what is involved in turning on lights via an app.

Simply attaching a sensor and adding connectivity doesn’t automatically make a device smarter or more useful.

Moreover, consumers certainly are not going to make that kind of effort and download an app for every appliance in their home. That would be arduous to manage, creating more work, rather than less. Rather than an assemblage of devices that can be controlled from smartphones, the homes of the future will integrate technology more seamlessly in ways that actually impart value. There will be less of the smartphone in the smart home.

Limiting the reliance on smartphones, and enabling the technology to recede into the background, requires three things. First, the sensors must be integrated, rather than controllable through a separate device. In the case of lighting, adding a motion sensor makes control via the light switch and via an app obsolete. The light turns on when someone walks into a room, and turns off when no one is there. The light bulb becomes an actor.

Second, it will require new interfaces. There are certain capabilities that smartphones provide, like security, that the homes of the future will have to replace. For example, right now people either access their homes using a key or, as of recently, via smart locks that are controlled from an app. In 2030, biometrical technology will enable people to get in. The surface of the door will recognize members of your family through their retina or skin structure. Residents will be able to communicate directly with the digitized “thing” without any intermediaries.

Third, the homes of the future will be smarter than they are today through learning algorithms. The things/devices will learn the residents’ preferences and use those to predict behaviors. It will not be necessary to program a light timer or a thermostat because the light already knows the residents’ movements and behaviors.

Knowledge of the preferred setting enables the device to simulate your presence when you are out and automatically regulate it to your liking when you are in. Devices that adapt to users’ habits over time will create a very intimate way of individualizing one’s home.

The other major trend that will shape the connected home over the next few decades is sustainability. Smart materials will make homes leaner and more energy efficient. One example is smart window glass, enabled by digitized shades, that will automatically darken when there is too much sun, meaning shutters are no longer necessary.

In addition, homes will become sustainable through the addition of a digital layer. Multifunctional devices will serve as platforms that make single-function devices obsolete. For instance, enhancing a light bulb with sensors turns it into a security system, because the bulb can alert the security service when it senses an unexpected presence, thereby making regular alarms obsolete.

People search for ways to uncomplicate their lives, or at least their homes, rather than the opposite. Technology is supposed to help us do that — but simply attaching a sensor and adding connectivity doesn’t automatically make a device smarter or more useful. A deep integration of connectivity and sensors applied to clear use cases will finally distinguish a smart home device and service from just digitized ones.

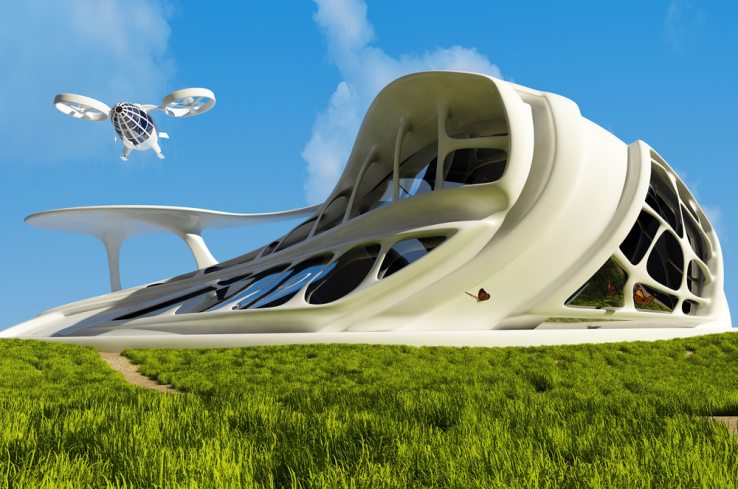

Featured Image: iurii/Shutterstock