Mark your Google calendars because from today ‘Don’t be evil’ rides again, via the DeepMind AI division of the Alphabet ad giant, as a Hippocratic assurance to ‘Do no harm’.

It’s no small irony that DeepMind’s new mantra for its healthcare push, voiced by co-founder Mustafa Suleyman at an outreach event today for patients to hear what the Google-owned company wants to build with U.K. National Health Service data, is uncomfortably close to its old one — i.e. the one that embarrassingly fell out of favor.

Suleyman cited the Hippocratic oath when discussing his takeaways from patient feedback on the company’s plans.

“[Do no harm] has to be a mantra we repeat and becomes an inherent part of our process,” he said towards the end of the three hour discussion session which was live streamed on YouTube (with a call for comments via a #DMHpatients Twitter hashtag).

“And [do no harm] should be the first measure of success before any deployment or before we attempt to demonstrate any utility and patient benefit,” he added.

After taking questions and listening to views from the small group of patients, health professionals and members of the public selected by the company to be in the audience, Suleyman flagged other takeaways. One of which was the need to widen access to the patient engagement channel DeepMind has now opened up.

He conceded it was unfortunate the event had been held in Google’s shiny, central London offices.

“As you say this is a fancy, intimidating building and I’m sorry for that, in some ways, it’s a shame that that’s the tone. I really agree with you that we have to find other spaces, community spaces that are more accessible to a more diverse group of people,” he said.

“As we formalize the process [of listening to patients] we want to make sure that there are other people being paid around the table and patients’ contributions should also be paid, and we’ll make sure that that’s the case. Potentially we should be thinking about how to run sessions like these on the weekends or in the evenings, when different stakeholders might have more time to get involved,” he added.

Alphabet’s AI division also said today it is intending to “define” what it dubs a “patient involvement strategy” by 2017.

Although DeepMind kicked off data-sharing collaborations with the NHS last fall — inking a wide-ranging data-sharing agreement with London’s Royal Free NHS Trust in September 2015 — and only publicly revealing the DeepMind Health initiative this February, two months after beginning hospital user tests of one of the apps it’s co-developing with the Royal Free… So it’s hard not to see its attitude towards patient engagement and involvement as something of an afterthought up to now.

Controversy and scrutiny

It also looks like a response to the controversy generated earlier this year by DeepMind’s first publicly announced collaboration with an NHS Trust (the Royal Free) — given that criticism of that project (Streams, an app for identifying acute kidney injury) has focused on how much patient identifiable data the Google-owned company is being given access to power the app, without patient knowledge, let alone consultation or consent. (DeepMind and the Royal Free maintain they do not need patient consent to share the data in that instance as they say the app is for direct patient care — a point the company now reiterates on its website, in a section labeled ‘Information Governance‘.)

The UK’s data protection watchdog, the ICO, is investigating complaints about the Streams app. The National Data Guardian, which is tasked with ensuring citizens’ health data is safeguarded and used properly, is also taking a closer look at how data is being shared. Streams was also not registered as a medical device prior to being tested in hospitals — but should have been, according to the MHRA regulatory body. So DeepMind Health’s modus operandi has already rocked a fair few boats — even as Suleyman was at pains to stress it’s “very early days” for DeepMind Health in his public comments today.

Tellingly the Google-owned company also now has a section of its Health website labeled ‘For Patients‘, where it describes its intention to create “meaningful patient involvement” and claims it is “incorporating patient and public involvement (PPI) at every stage of our projects”. (Although here, again, it notes another future intention: to create a patient advisory group to “contribute more extensively to our projects” — suggesting it could have done much more to involve patients in its first wave of NHS projects and research partnerships.)

“What we’re really doing today is to try and invite people openly to come and help us design the mechanism of interaction,” said Suleyman, summing up DeepMind’s intention for the outreach event. “Many people in this room have much more expertise and experience than we do and we recognize that we have a lot to learn here, and so today I think is an opportunity for us to learn. We’re really grateful for people’s time. We recognize that it’s valuable and we really think this is potentially an opportunity to do this the right way.”

He did not directly reference the Streams app data-sharing controversy, although the entire session was structured to illustrate (as DeepMind views it) the benefits of sharing health data for patients and health outcomes — and thus create a strong narrative to implicitly defend its actions — with much talk of the economic squeeze on the publicly funded NHS and the need to move towards earlier diagnosis of conditions to save resources as well as lives. Tl;dr: DeepMind’s sales pitch to grease the NHS health data funnel is that AI could automate efficiency savings for a chronically cash-strapped NHS. Ergo: you can’t afford not to give us your data!

And while Google’s podium included speakers who do not work directly for Alphabet, all speakers at the event were selected by the company to speak, so unsurprisingly aligned with its views. For example, we heard from Graham Silk of health data sharing advocacy group, Empower: Data4Health, rather than — say — Phil Booth from health data privacy advocacy group MedConfidential, which has been critical of DeepMind’s handling of NHS data.

Point is, if you’re creating the ‘public’ forum, you’re controlling (in large part) the scope and tone of the debate. As indeed Google has attempted to do before on other tech-policy intersections relevant to its business interests — also, incidentally, after being forced to respond to outside events (such as when it marshaled its resources to lobby against the European Court of Justice’s right to be forgotten ruling).

Payment by results

That said, today’s audience was inevitably a little less on point, given the event was at least theoretically open to any member of the public to apply for one of the 120 seats (although we don’t know how DeepMind selected participants). And audience members did at least raise the other big potential benefit of health data sharing: i.e. the financial benefit to Alphabet’s bottom line — by asking how DeepMind intends to monetize any machine learning algorithms it develops using the public data it is being given free access to.

On the business model question, Suleyman suggested a form of payment by results model is where Google’s thinking is at this nascent stage, as it seeks access to more public heath data-sets to feed machine algorithms that it hopes will deliver profit-bearing fruit in time.

“We have to build a sustainable business model on this. We’ve been clear about that from the outset. And what we’ve avoided doing is nailing that down too early — and luckily we have the resources to explore what the most effective business model would be around our interventions so that essentially we get paid when we deliver value. That’s what we would really like to do. The existing providers get paid for their activity — the vast majority, if not all, of their payments are delivered when that piece of software is shipped,” he said.

“What we would like to do is get paid, at least some proportion of what we get paid, to be connected to the actual concrete, clinical outcomes. And I think that’s another area where patients can really play an active role in helping us to identify what the important metrics are to patients — as well as the hospital, in terms of its efficiency and the way that it runs itself. I think that’s going to be a really challenging aspect of the model but we’re super committed to trying to innovate on that as much as we do on the technology.”

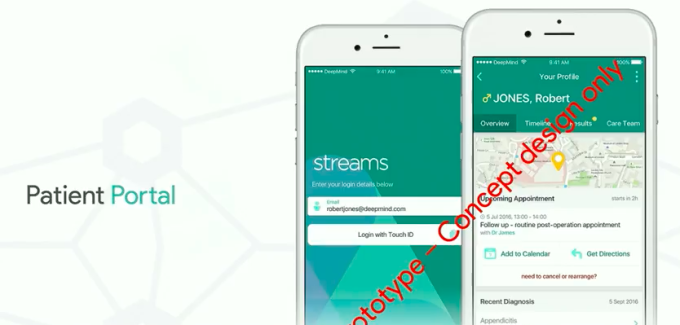

During his talk, Suleyman also spent time presenting a couple of slick-looking concept health apps for patients and doctors, designed to allow them to view and interact with health data on their phones — a prototype concept DeepMind is calling Patient Portal.

“Here we have Robert at home, reading through his data at home from his recent appointment,” he said, introducing one of the apps as if he were pitching an idea at a startup competition. “What he’s been able to do is see that he’s got an upcoming follow up appointment, a routine post-op appointment, where it is, and confirm that he’s able to attend… potentially he can get directions and also add it to his personal calendar.”

However the concept apps are pure vapourware at this point. DeepMind has not started work on Patient Portal app, Suleyman confirmed, going on to underwhelmingly describe the concepts as “the sorts of things that we might like to expect over the coming years”.

Nor is it clear how any such a visions of an app-delivered NHS could be achieved in any near term timeframe, given all the extant NHS systems that it would need to integrate — and, crucially, be comfortable sharing data — with DeepMind in order to realize the promise of real-time health data nestling under the fingertips of patients and doctors in a friendly smartphone format.

So really the concept apps were the most blatant part of DeepMind’s sales pitch today — using the familiarity and popularity of smartphone apps to try to win over the UK public to an alternative vision for the future of NHS healthcare delivery. One which would necessitate all their data being opened to a third party commercial entity to manage and control — and be paid for doing so. ‘If only those pesky information governance processes would step aside we could get on with saving lives and prettifying your blood test results in handy app form’, was the not-so-subtle subtext here.

Not everyone on the #DMHpatients hashtag was convinced with the calls to loosen up information governance, however…

Safe to say, DeepMind trying to recruit the user/general public to apply political pressure on its behalf to achieve — for all Suleyman’s talk of ‘social impact missions’ — commercial, profit-driven ends is a pretty standard playbook for tech firms seeking to workaround business barriers created by regulation. Just in this case it’s not Uber getting on-demand ride hailers to protest at ‘out-of-date city authorities’ getting in the way of their ride home, it’s an ad targeting giant seeking to encourage a far more liberal attitude to the sharing of individuals’ health data (data which has also been taxpayer funded, under the UK’s free-at-the-point-of-use NHS).

Security concerns

The first question from the audience following Suleyman’s presentation of the Patient Portal concept highlights the uphill climb DeepMind faces to convince the UK public to trust a commercial giant with their health data — with the questioner zeroing in on security and privacy concerns, something Suleyman’s presentation had glossed over.

Referring to DeepMind’s concept apps, a patient called Bernie noted: “You did not mention anything about how that information on the phone would be protected”, going on to ask where the data would be kept — on a doctor’s personal phone or a hospital-owned device? — and adding: “Would it not be safer for a mobile phone or something that would stay in the hospital so that that information didn’t actually go out of the hospital?”

Suleyman responded that streaming data to devices and using secure elements on smartphones are some of the ways DeepMind believes it can secure patient data to enable a Patient Portal style scenario of app-enabled healthcare.

We think that there are methods for ensuring that that data can only be accessed by the right person and at the right time.

“The plan is to stream data so that it’s not actually stored on the local mobile device. The objective is to try to make that data available when a particular clinician or indeed one day a patient needs and wants to access that data. At the moment we already have techniques for streaming that data in a very secure way so when your email is checked, for example, we have the best security infrastructure, the best controls in place to make sure that only you can access that data. And so whether that’s via a passcode on your mobile phone or fingerprint recognition we think that there are methods for ensuring that that data can only be accessed by the right person and at the right time,” he said.

“One approach [for which devices do we stream the data to] is to stream it to Trust owned devices. And we will make that possible as well. So where Trusts have invested in smartphones just like they have done with pagers that’s definitely possible. We also think it’s technically possible to do that to personal mobile devices as well, of the clinicians. And the way that this would work is there would be an encrypted operating shell — or OS — within the mobile phone which won’t touch other data on that phone. And that will be controlled by the Trust. So, for example, the data and the streaming and the application won’t be accessible out of, say, Trust wi-fi. It will be possible to log and record every access or edit or update to the data by that clinician. And so this will product an audit trail of essentially who has looked at which piece of data at which point.”

“There’s precedent at being able to do this very successfully in many other areas so technically this is a very mature set of tools and systems. It hasn’t reached healthcare yet, and so we’ll need to be very, very careful and involve lots of people in the way that we design and deploy that approach but we do believe that it’s technically possible to do it in a very, very secure way,” he added.

A pitch not a promise

At various points during the presentation Suleyman talked about the potential of artificial intelligence, describing AI as DeepMind’s “core expertise”, and adding that it as “very important that we can leverage our core expertise to try and advance the cutting edge of research”. Yet always qualifying the company’s ability to achieve results via AI as only that: a possibility.

He mentioned DeepMind’s research collaboration with Moorfields eye hospital, where it is using machine learning to try to automate analysis of retinal eye scans, and dubbed another research collaboration — with University College London Hospitals, which is looking at ways to use AI to automate radiotherapy treatment targeting — as “early research”. “We think this might be something that we could potentially contribute to,” he added, injecting yet another qualifier.

During the event it was increasing evident that DeepMind’s pitch to transform healthcare outcomes via machine learning algorithms is just that: a pitch, not a promise. The company has gained access to a lot of NHS data already but it does not yet have data to prove the effectiveness of AI for predicting and/or diagnosing disease and improving healthcare outcomes at scale. It needs the data to feed the algorithms to build the models before it can do that. So really it needs access to the large data-sets the NHS holds if it is to build anything of worth.

DeepMind is therefore in the tricky position of having to sell the UK public on providing free access to their most sensitive personal data before it can offer any concrete benefits in return. Without public buy-in it will struggle to access the pipeline of data it needs as its lifeblood. So you really have to wonder why it’s taken the company the best part of a year to realize how critically it needs to fully involve and engage patients with what DeepMind Health is doing.

Concluding its debut patient outreach event, Suleyman made a direct appeal for public involvement in what he dubbed “our process” — saying DeepMind is seeking help to determine what to prioritize as it builds clinical apps in collaboration with NHS Trusts willing to share data with the Google division.

And, again, a public personally bought into specific future healthcare apps and outcomes is likely to be far more supportive, and far less suspicious, of a commercial entity asking for its health data. (And, as many Silicon Valley tech giants could tell you, winning public support is the go-to strategy to sway regulatory rigidity these days.) So it’s not hard to see what DeepMind is doing here — and it boils down to burnishing its PR credentials. Yet holding what was supposed to be a ‘patient-centric’ event in swanky London offices underscores just how far removed their thinking still is from the patients they hope to serve.

We don’t expect this to be an opportunity for free feedback on our products. That’s not what we’re here to do; we’re here to invite criticism.

“We really want to put patients, families, carers and members of the public at the heart of our work. We’ve tried from the start I think to put the voice of clinicians and to some extent patients at the centre of what we do. And we see this as really very early days. And so we invite you to participate directly in our process,” he said.

“Importantly we have the choice of lots of different priorities for our clinical apps. there are lots of different directions we could go in and we recognize it’s important to involve lots of different stakeholders in settings those priorities. So far we’ve done our best to involve a bunch of diverse stakeholders but now we think it’s time to sort of formalize that process and have that as an inherent part of what we do, going forward.”

“We also think that it’s an opportunity for people to play a role as critical friends to help us to get this right. So we don’t expect this to be an opportunity for free feedback on our products. That’s not what we’re here to do; we’re here to invite criticism and essentially pay people to be part of a rigorous process, and not pay people where that’s appropriate too,” he added.