Now that Amazon has said that it’s taking its ball and going home rather than deal with mean, pushy New Yorkers, outside observers are giving off the sense that the city (and its local politicians) are losing out for their recalcitrance.

They’re wrong.

New York City is running at about a 4.3 percent unemployment rate — higher than the national average of 3.9 percent, but a respectable number for jobs. Amazon’s promise of 25,000 jobs (high-paying jobs) may have reduced that number, but there’s no guarantee that those jobs would be filled by New Yorkers or Queens residents more specifically — and every indication that they would have gone to Amazon employees coming from somewhere else.

Remember, Amazon employees were buying real estate in Queens before the deal was even announced.

The response that New Yorkers are idiots for not giving Amazon (one of the most valuable companies in the world) billions in tax incentives to build an office tower in one of its boroughs is another sign of how the country privileges business interests above civic ones.

There are things that New York can do to boost its local economy without giving away the store to Amazon. There are incentives that could go to businesses already in New York to establish offices in Queens.

More importantly, local Queens residents had legitimate concerns about how their neighborhood would be transformed by Amazon’s entrance into the borough.

That’s not to say that local politicians may not have overplayed their hand. New York local politics is no stranger to graft, corruption, shakedowns or funny business (I wasn’t in the room for the negotiations), but it’s safe to say that “mistakes were made” on both sides.

In the long run, Amazon would have been a benefit to the New York economy — and had the company’s executives made a good-faith effort to listen to the concerns of local residents, perhaps it could have come out looking like a winner.

Because there are legitimate reasons to expect Amazon to be a benefit to the New York economy. As Noah Smith wrote in Bloomberg after the deal was announced:

Amazon will pay property tax on its new Long Island City offices. It will pay corporate tax — not just on its profits, but on its capital base. Its employees, especially highly paid ones, will pay the city’s personal income tax. Those taxes, of course, will be somewhat offset by the incentives that the city has promised the company — up to $2 billion, depending on how many people the company hires and how many facilities it builds. Those incentives were a wasteful way to attract corporate investment. But in the long run, the tax revenue New York City gets from HQ2 will probably far exceed the cost.

And that’s not even taking into account Amazon’s effect on surrounding businesses and property values. Other technology companies will want to move to Queens now that Amazon is there. Their employees will spend their money locally, buying everything from lattes to MRIs. Some estimates place HQ2’s local economic boost at $17 billion a year. Even dividing that in half, and even assuming that the estimate is optimistic by a factor of 2 or 3, it seems likely that the economic benefit Queens reaps from HQ2 will quickly exceed the upfront cost — unlike, say, Wisconsin’s ill-advised Foxconn factory.

Those benefits are true, but harder to quantify for a city like New York when taken against the impact those jobs and spending would have on the fabric of the local economy and the housing, transit and government services that new residents would demand.

The livability crisis that’s currently afflicting Seattle and San Francisco is evidence of how cities need to be careful what they wish for when it comes to the explosive growth of technology companies (and the attendant wealth that comes with it) in their metropolises.

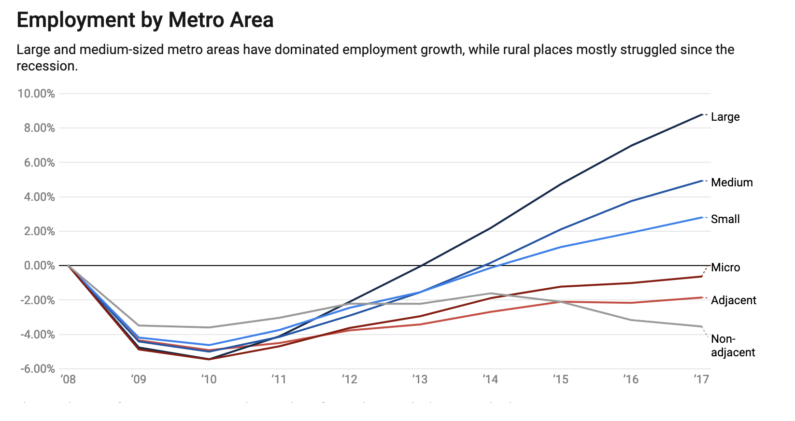

In any event, the urban landscape of the U.S. is being radically reshaped by technology companies — creating cities that are haves and have-nots much as technology has bifurcated the national economy into digital haves and have nots.

As Mark Muro and Robert Maxim of the Brookings Institute noted in this piece for US News and World Report:

Scholars have for years suspected that tech might alter the hierarchy of cities, given its bias toward skilled workers. More than a decade ago, researchers Paul Beaudry, Mark Doms and Ethan G. Lewis showed cities that adopted personal computers earliest and fastest saw their relative wages increase the quickest. Now, there is more evidence – including in our own work – that digital technologies are contributing heavily to the divergence of metro economies and the pull away of superstar cities like Boston and San Francisco from more ordinary ones, with painful impacts.

Recently, Princeton economist Elisa Giannone demonstrated that the divergence of cities’ wages since 1980 – after decades of convergence – reflects a mix of technology’s increased rewards to highly skilled tech workers and tech-driven industry clustering. Likewise, Brookings research has shown that a short list of highly digital, often coastal tech hubs is growing even more digital and pulling farther away from the pack on measures of growth and income. What we call the “digitization of everything” is in this way exacerbating the unevenness of America’s economic landscape.

It’s far easier to make the case that Amazon’s decision to set up regional offices in Nashville will have far more positive outcomes for that city.

But making American cities compete beauty pageant-style and bend over backwards to appease a multi-billion-dollar corporation is pretty gross — and a poor read of national sentiment around the roles that technology companies play in modern American society.

As an example of how to expand in a city without invoking the wrath of the local community, observers need only look at how Google is expanding in New York. The company is planning to add 14,000 jobs in the city and has committed to $1 billion in spending to upgrade its West side campuses.

Ostensibly, Google is expanding its presence in New York to compete for the talent it sees coming from the city (or coming to the city) and because New York is strategically important. Amazon’s decision to forsake New York means that it’s losing access to that talent and creating opportunities for other tech companies to come in and take its place — or for local companies to retain their edge.

Here’s hoping that New York’s local tech community can supply Queens with those 25,000 jobs by building the next Amazon — and working with the community to do it.

These days it seems like Democracy is a religion that’s replaced God with money. The pushback against Amazon shows that New York at least is adding civic responsibility into that equation somewhere.