![]()

In the era of the “selfie”, of the relentless click-and-publish images on social media, of the mega sensors replete with megapixels, we are witnessing an unpredictable resurgence of many ancient photographic devices and techniques.

Wet collodion (tintypes) and many other alternative photo processes are being keenly rediscovered today and there is an ever-growing plethora of workshop available to those who want to learn and practice them.

A primitive photographer myself, a practitioner of what I like to define “slow photography” for most of my professional life, I observe this phenomenon with great interest, wondering about what its deepest rationale might be.

The amazing and light-fast technology that permeates our lives can become overwhelming at times. Images are indeed one of the most widespread and immediate forms of communication nowadays, when an ever-decreasing attention span makes just reading a few paragraphs a daunting task for many.

At the same time, creating digital images is devoid of the tactile, hand-dirtying, artisanal, alchemic qualities typical of the silver process heritage.

Today lenses and cameras are precisely designed and built by computers, there is no more space for the serendipitous human error neither in the photographic machines nor in the images they produce. Everything is simplified and automated, bringing the original Kodak Brownie advertising promise “ you press the button- we do the rest” to an almost dystopian level, thus hampering some peoples’ vision and their enjoyment of the creative process.

That is certainly my case and, given the choice, I’ll always opt for an ancient glass and wood large format view camera versus the latest digital device.

I suppose there are other factors too: In analog photography the creative process doesn’t end downloading your files to a computer or uploading them to social media, lost in a binary void forever, but it continues in the darkroom, where one carefully chosen image undergoes a complex voyage towards becoming a print, a tactile, permanent, often unique expression of the photographer’s vision.

To sum up, it appears that the impermanence of digital is finally starting to feel uncomfortable to some, hence a reversal to think more, click less, dabble with wet techniques from the past to create images that can actually still exist in the future.

Along those lines, I am happy to report the recent re-introduction on the market of a long gone photographic medium: dry glass plates.

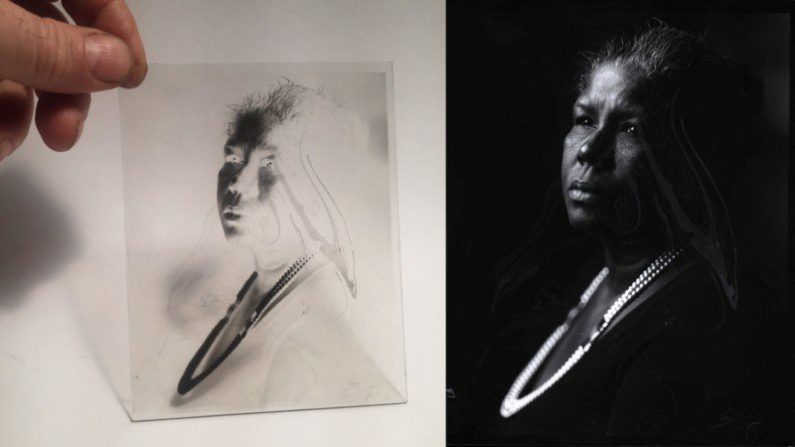

![]()

![]()

Dry glass plates, invented by Dr. Richard L. Maddox in 1871, were a major advancement for photographers who until then were mostly using the wet collodion process. Wet collodion required to be poured just before taking the photograph and developed shortly afterward, something rather difficult and time-consuming outside of a studio environment.

Dry glass plates instead, being pre-coated with a light-sensitive gelatin could be easily transported to external locations and the photos developed at a later time, back in the darkroom, greatly helping photographers to expand their business in outside locations. You can admire a nearly unknown itinerant seed vendor-photographer exquisite dry plates photos taken on the Italian Alps here.

While I am familiar and have practiced in the past wet collodion photography, I too, a century later, find dry plates portability a great advantage over tintypes. With dry plates, I can even fly commercially, without having to worry about the strict Airlines regulations against the poisonous and explosive wet collodion chemistry.

![]()

![]()

Shooting these new old dry plates is not completely devoid of problems, yet, but things are improving rapidly. The first batches had some flaws and coating issues but that, by now, has been completely resolved.

The man that made dry plates photography possible again is Mr. Jason Lane, a brilliant optical engineer based in New Hampshire, who has a deep love and understanding of photographic media and techniques from a bygone era.

![]()

Mr. Lane’s production is still completely artisanal and made in U.S.A.: he painstakingly hand-coats his dry plates, boxes them and ships them.

A one-man operation fuels this unexpected and welcome renaissance inspired by the past but with an eye to the future, giving us the opportunity to experiment with one of the most archival-stable and fascinating photographic technology from the beginning of last century.

![]()

![]()

In a world that is often keen to forget and foolishly dismiss as useless many valuable assets from the heritage of mankind, not only in photography but also in everything else, including oral tradition, popular culture, and art, I find Mr. Lane’s work extremely remarkable and inspiring.

Editor’s note: Jason Lane has been selling his dry plates for several months now. The emulsion has a “normal” sensitivity, so it responds to UV and blue.

“In this way, it shares a lot of characteristics with wet plate, combining them with characteristics of film I really enjoy the look of the handmade plate era, and it seems I’m not the only one,” Lane told PetaPixel back in January.

Lane is selling a few standard formats and is also open to making custom plates of all sizes — he has made and delivered plates as large as 12×20″ and as small as 35mm.

You can find out more about Lane’s plates and purchase you own through his website, Facebook page, and Etsy store.

About the author: Giovanni Savino is a New York-based photographer and cinematographer. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can find more of Savino’s work on his website and Instagram. This article was also published here.

Image credits: Header photos by Giovanni Savino. All other photos by Jason Lane.