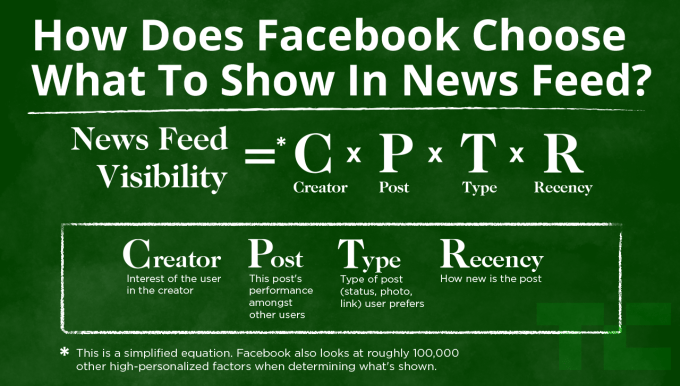

Facebook built two versions of a fix for clickbait this year, and decided to trust algorithmic machine learning detection instead of only user behavior, a Facebook spokesperson tells TechCrunch.

Today Facebook was hit with more allegations its distribution of fake news helped elect Donald Trump. A new Gizmodo report saying Facebook shelved a planned update earlier this year that could have identified fake news because it would disproportionately demote right-wing news outlets.

Facebook directly denies this, telling TechCrunch “The article’s allegation is not true. We did not build and withhold any News Feed changes based on their potential impact on any one political party.”

However, TechCrunch has pulled more details from Facebook about the update Gizmodo discusses.

Back in January 2015, Facebook rolled out an update designed to combat hoax news stories, which demoted links that were heavily flagged as fake by users, and that were often deleted later by users who posted them. That system is still in place.

Back in January 2015, Facebook rolled out an update designed to combat hoax news stories, which demoted links that were heavily flagged as fake by users, and that were often deleted later by users who posted them. That system is still in place.

In August 2016, Facebook released another News Feed update designed to reduce clickbait stories. Facebook trained a machine learning algorithm by having humans identify common phrases in old news headlines of clickbait stories. The machine learning system then would identify and demote future stories that featured those clickbait phrases.

According to Facebook, it developed two different options for how the 2016 clickbait update would work. One was a classifier based off the 2015 hoax detector based on user reports, and another was the machine learning classifier built specifically for detecting clickbait via computer algorithm.

Facebook says it found the specially-made machine learning clickbait detector performed better with fewer false positives and false negatives, so that’s what Facebook released. It’s possible that that the unreleased version is what Gizmodo is referring to as the shelved update. Facebook tells me that unbalanced clickbait demotion of right-wing stories wasn’t why it wasn’t released, but political leaning could still be a concern.

The choice to rely on a machine learning algorithm rather than centering the fix around user reports aligns with Facebook’s recent push to reduce the potential for human bias in its curation, which itself has been problematic.

A Gizmodo report earlier this year alleged that Facebook’s human Trend curators used their editorial freedom to suppress conservative trends. Facebook denied the allegations but fired its curation team, moving to a more algorithmic system without human-written Trend descriptions. Facebook was then criticized for fake stories becoming trends, and the New York Times reports “The Trending Topics episode paralyzed Facebook’s willingness to make any serious changes to its products that might compromise the perception of its objectivity.”

If Facebook had rolled out the unreleased version of its clickbait fix, it might have relied on the subjective opinions of staffers reviewing user reports about hard-to-classify clickbait stories the way it does with more cut-and-dry hoaxes. Meanwhile, political activists or trolls could have abused the reporting feature, mass-flagging accurate stories as false if they conflicted with their views.

This tricky situation is the inevitable result of engagement-ranked social feeds becoming massively popular distribution channels for news in a politically-polarized climate where campaign objectives and ad revenue incentivize misinformation.

Who Is The Arbiter Of Truth?

Facebook as well as other news distributors such as Twitter and Google have a challenge ahead. Clear hoaxes that can be disproven with facts are only part of the problem, and perhaps are easier to address. Exaggerated and heavily-spun stories that might be considered clickbait may prove tougher to fight.

Because Facebook and some other platforms reward engagement, news outlets are incentivized to frame stories as sensationally as possible. While long-running partisan outlets may be held accountable for exaggeration, newer outlets built specifically to take advantage of virality on networks like Facebook don’t face the same repercussions. They can focus on short-term traffic and ad revenue, and if people get fed up with their content, they can simply reboot with a different brand.

Simplifying user flagging of fake or exaggerated stories, appending fact-checking sites to suspicious articles, and withholding distribution from domains that haven’t proven their accuracy but prioritize monetization could be some ways to fight the avalanche of fake news. More clearly needs to be done.

But perhaps its risky to demand networks like Facebook become the truth police. That could force it to make more wide-reaching calls about what to censor that would inevitably invite blame. At least technology platforms that err on the side of ranking by engagement allow users to decide individually if what they read is false or exaggerated. Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg has reiterated this perspective, writing “I believe we must be extremely cautious about becoming arbiters of truth ourselves.”

Right now, Facebook is damned if does allow fake news to spread because it relies on users to think for themselves, but it’s damned if it doesn’t allow fake news to spread because it makes decisions about what to censor that remove the power of choice from its users. The social network will have to choose its next moves carefully.