The UK parliament has provided another telling glimpse behind the curtain of Facebook’s unregulated ad platform by publishing data on scores of pro-Brexit adverts which it distributed to UK voters during the 2016 referendum on European Union membership. The ads were run on behalf of several vote leave campaigns who paid a third company to use Facebook’s ad targeting tools.

The ads were run prior to Facebook having any disclosure rules for political ads. So there was no way for anyone other than each target recipient to know a particular ad existed or who it was being targeted at.

The targeting of the ads was carried out on Facebook’s platform by AggregateIQ, a Canadian data firm that has been linked to Cambridge Analytica/SCL — aka the political consultancy at the center of a massive Facebook data misuse storm, including by Facebook itself, which earlier this year told the UK parliament it had found billing and administration connections between the two.

Aggregate IQ is now under joint investigation by Canadian data watchdogs. But in 2016 the data firm was paid £3.5M by a number of Brexit supporting campaigns to spend on targeted social media advertising using Facebook as the primary conduit.

Facebook was asked by the UK parliament’s DCMS committee to disclose the Brexit ads — as part of its multi-month enquiry investigating fake news and the impact of online disinformation on democratic processes. The company eventually did so, releasing ads run by AIQ for the official Vote Leave campaign, BeLeave/Brexit Central, and DUP Vote Leave.

Several of the Brexit campaigns whose ads have now been made public were also recently found to have broken UK election law by breaching campaign spending limits. Most notably the Electoral Commission found that the youth-focused campaign, BeLeave, had been joint-working with the official Vote Leave campaign — yet the pair had not jointly declared spending thereby enabling the official campaign to overspend by almost half a million pounds. And that overspend went straight to Aggregate IQ to run targeted Facebook ads.

The committee has now published the Brexit ads that Facebook disclosed to it, more than two years after the referendum vote took place. Facebook also provided it with ad impression ranges and some targeting data which it has also published. The committee’s enquiry remains ongoing.

In a letter to the committee, Facebook says it’s unable to disclose ads run by AIQ for another Brexit campaign, Veterans for Britain, saying that campaign “has not permitted us to disclose that information to you”. So the view of the Brexit political ads we’re finally getting is by no means complete. Facebook’s platform also essentially enables anyone to be an advertiser — so it’s entirely possible other Brexit related messages were distributed using its ad tools.

In the case of the Brexit ads run by AIQ specifically, it’s not clear how many ad impressions they racked up in all. But total impressions look very sizable.

While some of what runs to many thousands of distinctly targeted ads which AIQ distributed via Facebook’s platform are listed as only garnering between 0-999 impressions apiece, according to Facebook’s data, others racked up far more views. Commonly listed ranges include 50,000 to 99,999 and 100,000 to 199,999 — with even higher ranges like 2M-4.9M and 5M-9.9M also listed.

One ad that generated ad impressions of between 2M-4.9M was targeted almost exclusively (99%) at English Facebook users — and included the claim that: “EU protectionism has prevented our generation from benefiting from key global trade deals. It is time we unite to give our country the freedom to be a prosperous and competitive nation!”

A spokesperson for the DCMS committee told us it hadn’t had a chance to compiled the thousands of ad impression ranges into a total ad impression range — but had rather published the data as it had received it from Facebook. We’ve also asked the company to prove an estimate on the total ad impressions and will update this story with any response.

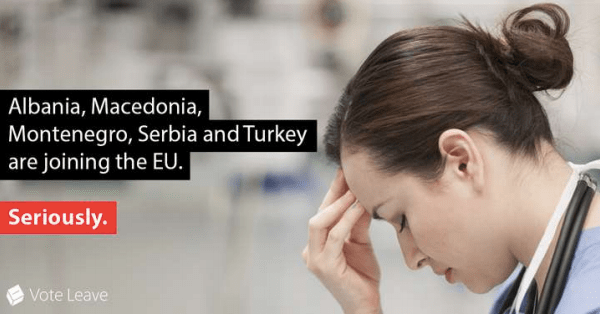

The ad creative used by these campaigns has been published as well and — across all of them — the adverts display a mixture of (roundly debunked) claims about suddenly being able to spend ‘£350M a week on the NHS’, rousing calls to ‘take back control’ (including a bunch of ‘hero’ shots of Boris Johnson), coupled with ample fearmongering about EU regulations ‘holding the UK back’ or posing a risk to UK jobs and wages; plus a lot of out-and-out ‘project fear’ messaging — with the official Vote Leave campaign especially deploying direct dogwhistle racism to stir up fear among voters about foreigners coming to the UK if it can’t control its own border or if the EU expands to add more countries…

At a glance, the Brexit ad creative is not as ‘out there’ as some of the wilder stuff the Kremlin was pumping onto Facebook’s platform to try to skew the 2016 U.S. election.

But the blatant xenophobia leaves a very bad taste.

In the case of Brexit Central/BeLeave, their ad creative was more subtle in its xenophobia — urging target recipients to back a “fair immigration system” or an “Australian-style points based system” but without making any direct references to any specific non-EU countries.

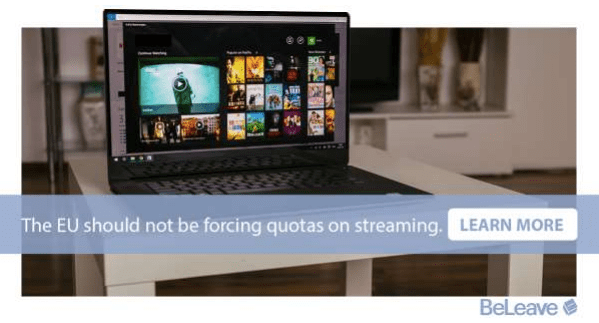

The youth campaign also created a couple of ads (below) which invoked consumer technology as a reason to back Brexit — with one appealing to users of ride-hailing and another to users of video streaming apps to reject the EU by suggesting its regulations might interfere with access to the services they use.

Ironically enough, it was London’s transport authority that withdrew Uber’s license to operate last year — in a regulatory decision that had absolutely nothing to do with the EU. (Uber has since appealed and got a 15-month reprieve.)

Though, also last year, the EU’s top court judged that a spade is a spade — and Uber is a transport company, not a mere technology platform. Though the ruling has not prevented Uber from continuing to operate and even expand ride-hailing services in Europe. Sure, it has to work more closely with city authorities now, but that means meshing with local priorities rather than seeking to override what local people want.

In a further irony, the EU also took steps to liberalize passenger transport services, back in 2007, issuing a directive that makes it harder for cities authorities to place their own controls on ride-hailing services. Albeit, evidently facts didn’t get a starring role in the vote leave Brexit ads.

As for quotas on streaming services, it’s a curious thing to complain about — especially to a youth-focused audience which you’re also targeting with ads claiming they’ll have better job prospects outside the EU.

The EU has merely suggested online streaming services should provide for and subsidize up to a third of their output of films and TV as being made in Europe.

Which seems unlikely to have a deleterious impact on European creative industries, given platforms would be contributing to the development of local audiovisual production. So — in plainer English — it should mean more money to support more creative jobs in Europe which many young people would probably love to have a crack at…

The publication of the Brexit ads is, above all, a reminder that online political advertising has been allowed to be a blackhole — and at times a cesspit — because cash-rich entities have been able to unaccountably exploit the obscurity of Facebook’s systemically dark ad targeting tools for their own ends, leaving no right of public objection let alone reply for the people as a whole whose lives are affected by political outcomes such as referendums.

Facebook has been making some voluntary changes to offer a degree of political ad disclosure, as it seeks to stave off regulatory rule. Whether its changes — which at best offer partial visibility — will go far enough remains to be seen. And of course they come too late to change the conversation around Brexit.

Which is why, earlier this month, the UK’s data watchdog calling for an ethical pause of political ad ops — saying there’s a risk of democracy being digitally undermined.

“It is important that there is greater and genuine transparency about the use of such techniques to ensure that people have control over their own data and that the law is upheld,” it wrote. “Without a high level of transparency – and therefore trust amongst citizens that their data is being used appropriately – we are at risk of developing a system of voter surveillance by default.”