In October 2017, online giants Twitter, Facebook and Google announced plans to voluntarily increase transparency for political advertising on their platforms. The three plans to tackle disinformation had roughly the same structure: funder disclaimers on political ads, stricter verification measures to prevent foreign entities from posting such ads, and varying formats of ad archives.

All three announcements came just before representatives from the companies were due to testify before Congress about Russian interference in the 2016 election and reflected fears of forthcoming regulation, as well as concessions to consumer pressure.

Since then, the companies have continued to attempt to address the issue of digital deception occurring on their platforms.

Google recently released a white paper detailing how it would deal with online disinformation campaigns across many of its products. In the run-up to the 2018 midterm elections, Facebook announced it would ban false information about voting. These efforts reflect an awareness that the public is concerned about the use of social media to manipulate their votes and is pushing for tech companies to actively address the issue.

These efforts at self-regulation are a step in the right direction — but they fall far short of providing the true transparency necessary to inform voters about who is trying to influence them. The lack of consistency in disclosure across platforms, indecision over issue ads, and inaction on wider digital deception issues including fake and automated accounts, harmful micro-targeting, and the exposure of user data are major defects of this self-governing model.

For example, individuals looking at Facebook’s ad transparency platform are currently able to see information about who viewed an ad that is not currently available on Google’s platform. However, on Google the same user can see top keywords for advertisements, or search political ads by district, which cannot be done on Facebook.

With this inconsistency in disclosure across platforms, users are not able to get a full picture of who is trying to influence them, which prevents them from being able to cast an informed vote.

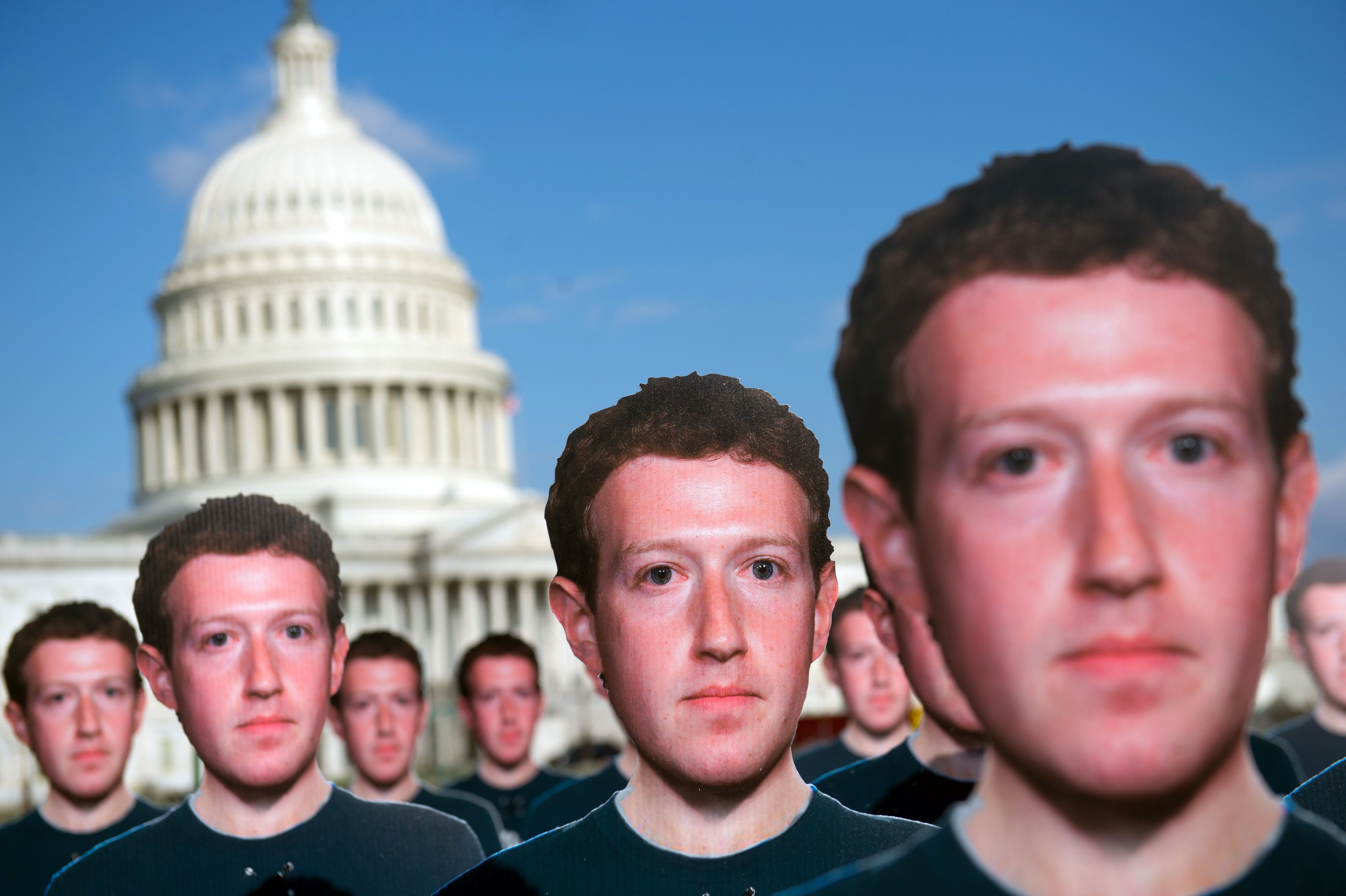

One hundred cardboard cutouts of Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg stand outside the US Capitol in Washington, DC, April 10, 2018. Advocacy group Avaaz is calling attention to what the groups says are hundreds of millions of fake accounts still spreading disinformation on Facebook. (Photo: SAUL LOEB/AFP/Getty Images)

Issue ads pose an additional problem. These are public communications that do not reference particular candidates, focusing instead on hot-button political issues such as gun control or immigration. Issue ads cannot currently be regulated in the same way that political communications that refer to a candidate can due to the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the First Amendment.

Moreover, as Bruce Flack, Twitter’s General Manager for Revenue Product, pointed out in a blog post addressing the platform’s impending transparency efforts, “there is currently no clear industry definition for issue-based ads.”

In the same post, Flack indicated a potential solution, writing, “We will work with our peer companies, other industry leaders, policy makers and ad partners to clearly define [issue ads] quickly and integrate them into the new approach mentioned above.” This post was written 18 months ago, but no definition has been established—possibly because tech companies are not collaborating to systemically confront digital deception.

This lack of collaboration damages the public’s right to be politically informed. If representatives from the platforms where digital deception occurs most often — Facebook, Twitter, and Google — were to form an independent advisory group that met regularly and worked with regulators and civil society to discuss solutions to digital deception, transparency and disclosure across the platforms would be more complete.

The platforms could look to the example set by the nuclear power industry, where national and international nonprofit advisory bodies facilitate cooperation among utilities to ensure nuclear safety. The World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO) connects all 115 nuclear power plant operators in 34 countries in order to facilitate the exchange of experience and expertise. The Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO) in the U.S. functions in a similar fashion but is able to institute tighter sanctions since it operates at the national level.

Similar to WANO and INPO, an independent advisory group for the technology sector could develop a consistent set of disclosure guidelines — based on policy regulations put in place by government — that would apply evenly across all social media platforms and search engines.

These guidelines would hopefully include a unified database of ads purchased by political groups as well as clear and uniform disclaimers of the source of each ad, how much it cost, and who it targeted. Beyond paid ads, the industry group could develop guidelines to increase transparency for all communications by organized political entities, address computational propaganda, and determine how best to safeguard users’ data.

Additionally, if the companies were working together, they could set up a consistent definition of what an issue ad is and determine what transparency guidelines should apply. This is particularly relevant given policymakers’ limited authority to regulate issue ads.

Importantly, working together regularly would allow platforms to identify technological advances that might catch policymakers by surprise. Deepfakes — fabricated images, audio, or video that purport to be authentic — represent one area where technology companies will almost certainly be ahead of lawmakers’ expertise. If digital corporations were working together as well as cooperating with government agencies, they could flag new technologies like these in advance and help regulators determine the best way to maintain transparency in the face of a rapidly changing technological landscape.

Would such collaboration ever happen? The extensive aversion to regulation shown by these companies indicates a worrying preference towards appeasing advertisers at the expense of the American public.

However, in August 2018, in advance of the midterm elections, representatives from large tech firms did meet to discuss countering manipulation on their platforms. This followed a meeting in May with U.S. intelligence officials, also to discuss the midterm elections. Additionally, Facebook, Microsoft, Twitter, and YouTube formed the Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism to disrupt terrorists’ ability to promote extremist viewpoints on those platforms. This shows that when they are motivated, technology companies can work together.

It’s time for Facebook, Twitter, and Google to put their obligation to the public interest first and work together to systematically address the threat to democracy posed by digital deception.