![]()

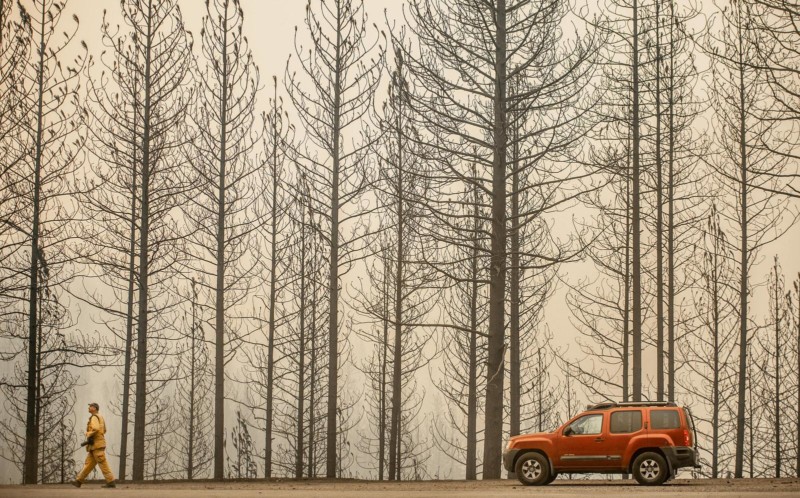

When historic wildfires raged across California last year, thousands of firefighters were deployed to combat them. And alongside those brave men and women were fearless wildfire photographers who raced to the front lines to document the devastation for the world’s eyes.

Warning: This article contains graphic and disturbing descriptions.

Through covering many of California’s biggest wildfires side-by-side over the years, some of these photographers have developed a close-knit camaraderie that provides both support and safety during dangerous assignments.

Take a look at the credit lines of news photos that emerged from fires such as the 2018 Camp Fire (the most deadly and destructive California wildfire ever), and you’ll likely see the names from this group of fire-chasing photographer friends: Noah Berger, Josh Edelson, Stephen Lam, Gabrielle Lurie, Justin Sullivan, and Marcus Yam.

Origins

These photographers met while covering different fires and while shooting for various media outlets and news agencies. Berger “got hooked” on wildfires after covering the Rim Fire of 2013 alongside Sullivan, whom he has known for about two decades now. Berger is a freelancer who often shoots for the Associated Press, SF Chronicle, and NY Times, while Sullivan is a staff photojournalist for Getty Images. Both men started their photojournalism careers in the mid-1990s.

Edelson (then an amateur hobbyist photographer) met Berger while he was covering a small fire on the streets of San Francisco in 2009. After answering some of Edelson’s questions about his job, Berger took Edelson under his wing and became his mentor. Berger would go on to become one of Edelson’s closest friends and a member of his wedding party.

Lurie (an SF Chronicle staff photographer), Lam, Berger, Edelson, and Sullivan are all based in the San Francisco Bay Area, so they’ve known each other from covering news as members of the region’s close-knit community of photojournalists. Yam is an LA Times staff photographer based in Los Angeles who met the group while covering fires.

Bonding as Friends

Over the past several years, the group has spent many hours together, living and working side-by-side at wildfires that dominate national headlines.

“We give each other a lot of s**t,” Edelson says. “Sometimes the humor helps keep things light considering the seriousness of what we see out there.”

The photographers also share everything from food to hotel rooms (when they can get one).

“During the Camp Fire, a bunch of us actually spent a few nights staying at this Airbnb with 14 beds in one giant space,” Lam says.

“We all eat meals together, sleep in close quarters, and share with one another,” Lurie says. “It’s pretty great. They make me feel safe and like we’re part of a family.”

Even outside of work, the photographers occasionally get together for meals, drinks, and even things like community service.

“I think the best memory of camaraderie was when the fire photographers and a group of San Francisco Bay Area journalists who covered the fires in Napa and Sonoma County came together to volunteer at the Redwood Empire Food Bank in Santa Rosa,” Sullivan says. “We all felt the need to give back to the community we covered that suffered so much loss. We packed nearly 5 tons of food that were given out to residents who were directly impacted by the fires.”

“We have all become close and keep up with each other regularly,” Sullivan says. “We have a group fire text chain where we keep up fire activity throughout the state. When a new fire starts, the text chain usually lights up with activity.”

Competition and Camaraderie

Photographers covering the same events and subjects are naturally in competition to capture the best and most newsworthy photos, so it may seem strange to outsiders that this group of wildfire photographers has become the closest of friends. What’s more, they even go out of their way to share information and collaborate on the field.

“We each want to have the best coverage every day, but we strive for that while still sharing info and helping each other to a degree that wouldn’t happen among most groups of photographers,” Berger says. “For example, at the Valley fire, one of us (I believe it was Stephen Lam) found a dead horse lying beside a road. Most photographers would just keep this to themselves, but he told us so we could all shoot it. It’s really done out of a spirit of friendship and camaraderie.”

“We talk about logistics a lot,” Edelson says. “For example, there was a scene where rescue workers were about to carry a body bag up a hill. Noah, Justin, and I were there. We quickly discussed how to shoot it so none of us ruined the others’ shot by getting in the frame.”

Shooting alongside each other also pushes each member of the group in their work.

“Each of us photographs things differently, with various approaches, focal lengths and so forth, so it’s not as if the competition to capture a storytelling image just disappears,” Lam says. “In fact, it inspires me to be a better photographer.”

“I love that we all have our own vision and shooting style that allows us to shoot the same scene with different results,” Sullivan says. “Knowing that 2 to 3 extremely talented photographers are shooting the same scene as I inspires me to really think about what I am shooting and to think outside of the box at how I will approach my coverage.

“When someone in the group gets a great photo or lands a front page of a national newspaper, we make sure congratulate that person and are genuinely proud of their achievement. There are never hard feelings or jealousy.”

“This is not common in most markets, but that’s how we do it up here,” Edelson adds.

Safety in Numbers

In addition to sharing information, resources, and inspiration, one of the biggest benefits to working collaboratively as a close-knit group of friends is safety. Even though the group rushes toward fires that the general public is trying to flee from, none of the photographers have gotten any serious injuries over the years, and that has a lot to do with the ways they watch out for each other.

“Being with a group that is well trained and understands how to navigate these dangerous fires is so important to me,” Sullivan says. “Being in a car with someone when you’re driving down roads that have fire on both sides with trees and power lines falling all around is so much better than trying to navigate it on your own.

“Having two or three people in a car when trying to get through these areas allows the driver to keep his eyes on the road while others in the car can keep an eye on hanging wires and other threats. Regardless of the situation, I feel one hundred percent safe when traveling with the group. We all have each other’s backs and I think knowing that allows me to produce the best work that I can.”

Berger recalls one incident during the 2015 Valley Fire that shows how traveling as a group in more than one car helps ensure safety:

“Josh was at a burning house and let us know. Stephen and I were trying to get there in two cars caravanning. At one point, there were a lot of rocks/small boulders in the road and there was fire on both sides of us. This was at night in an area with no firefighters around. Stephen got a flat driving over one of the rocks and his tire was losing air fast.

“We made it to the burning house in time to shoot it, but to get out we had to stop every couple minutes to pump air into Stephen’s tire. I stayed behind him, ready to throw him and his gear in my SUV if it because impossible for him to make it out in his.”

While in the midst of a wildfire, the group pools their eyes and minds together to spot dangers and weigh risks.

“We’ll point out power lines on the ground, motioning towards enclosing flames about to cut off our positions, calling attention to smoldering trees or power poles so we don’t stand under them,” Edelson says. “All these little seemingly benign comments aggregate into the bigger picture that keeps us all safe.”

“I don’t think any of us would leave the other in peril… even if it meant risking our lives,” Berger says.

Always Be Prepared

Wildfire photographers are well prepared in both their equipment and their training before going to a major fire. In the area of gear, the photographers generally wear what firefighters wear: helmet, respirator masks, gloves, goggles, fire suits, and boots.

But even more important than these safety items is knowing when to be where.

“You want to get in the ‘black’, land that has already burned, even if it’s still flaming, rather than being in the ‘green’, land that hasn’t burned,” Berger says. “There are still shots of big flames behind the leading edge, but the wind and fire are not as intense.

“One other strategy that we’ve learned from training and firefighters is to make note of safety zones. If you have a big enough clearing (asphalt, dirt, rock) with no vegetation, you can shelter in/by your car as the fire front burns over you. I think I’ve only used this when firefighters were in that safety zone — it would be scary to ride that out without them around.”

“We always leave our engines on and pointed outward in the direction we may need to go in case of escape,” Edelson says. “We also pay attention to the direction of the wind and ensure that we have at least two escape routes.

“Never stand or park under power lines or a tree. Even after the fire passes, trees and power poles continue to smolder, weakening them enough to fall at random. […] We also always assume power lines are energized even if we’re told they are not. Sometimes there can be surges of power coursing through downed lines. Better to not take a chance.”

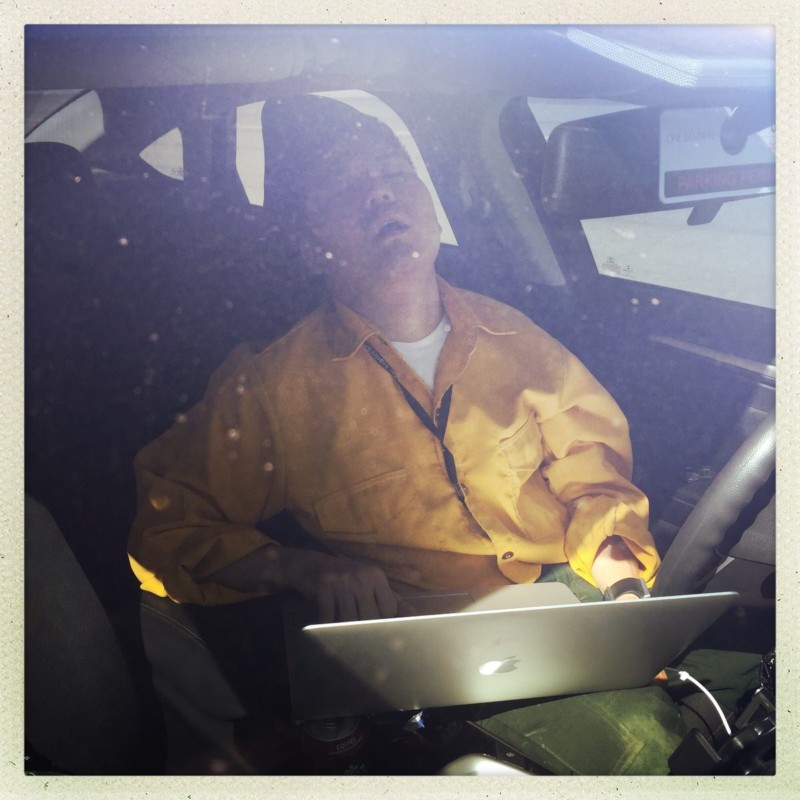

With years of wildfire experience under his belt, Berger is a seasoned vet of the group that some of the others often look to for advice and direction.

“To be honest I’m not an adrenaline junkie,” Lurie says. “So I’m very cautious and I tell the guys when I’m nervous and we talk through things. They’re very cool about it all and we all make sure we’re comfortable.

“Noah is our barometer. If he goes up to shoot a fire, we follow behind. Noah is someone who wants to get the shot and push himself but he’s safe. Recently we talked about going down a road where we thought structures were burning but the wind seemed too strong and he said, ‘Nah, I don’t think we should do it,’ and I really respect that. He wants the shot more than anyone but he knows when to back down.”

Emotional Support

The power of the group’s friendship goes well beyond the time and place of each wildfire, as witnessing and photographing death and destruction can leave a mental and emotional burden that can be difficult to bear.

“I was particularly hit hard [by the Camp Fire], as I gained unprecedented access to follow in the search for bodies and I came to see a gruesome scene that I couldn’t even file to my editors,” Edelson says. “I arrived at a burned residence where rescue workers had found a body. It was laying under a tin roof that had collapsed during the burn. When they lifted it, I’ll never forget the look on her face.

“I think it was a woman, but not really sure. She was completely charred and stiff. I remember seeing her face. It looked like the expression of fear she felt when she realized she was about to die was frozen on her face and stayed that way. She was gritting her teeth and her eyelids were gone. It was horrific.”

“The destruction of everyone’s property is pretty disturbing and hearing their stories is so sad,” Lurie says. “People have worked tirelessly their whole lives to create a home and then in a matter of hours, it’s all gone.

“After [the Santa Rosa fires of 2017] I was stoic for three weeks. Then one day I drove up there and just started sobbing for like ten minutes. I collected myself and kept going.”

In the aftermath of fires, the photographers continue to check up on each other to make sure everyone is coping well.

“The fire group is very supportive and have been checking in on each other on a regular basis,” Sullivan says. “We have had several open conversations about the importance of being willing to talk through some of the horrific things that are seeing.”

“[W]e sometimes have a hard time getting re-acclimated to normal life after being in the fire zone for so long,” Edelson says. “Sometimes I’ll see a tree or a house just doing something normal like going to the store, and I find myself imagining what it would look like burning.

“It leaves a mark on you. On your mind. […] It’s nice to talk to people who have been through it. No one else really understands.”

Image credits: Header photos by Noah Berger (left) and Stephen Lam (right). Featured thumbnail/photo by Stephen Lam.