Game development is a risky business — in the literal sense, that is. Hoping a title becomes a million-seller and justifies its staff and years of gestation often leads to the ruin of game studios and publishers. And that’s if the game ever even releases. But Good Shepherd has found that careful curation, help with pain points like localization, and other avenues of stewardship can make games as reliable an investment as a mutual fund, but considerably more profitable.

The company, founded in 2011 as Gambitious but eventually (and I’d say wisely) rebranding under the current name, basically finds promising games and makes sure they get the best chance at success possible. And it works: they’ve helped usher 15 games into the world, 12 of which have been out for at least a year and 9 of which are already profitable. The portfolio as a whole is turning a 30 percent profit.

More easily said than done. Independent game developers aren’t exactly widget makers; even promising titles can and do end up in development hell as the narrative is reworked, scope is adjusted, art styles are redone, and so on. A good publisher or backer will make sure these don’t torpedo the whole project.

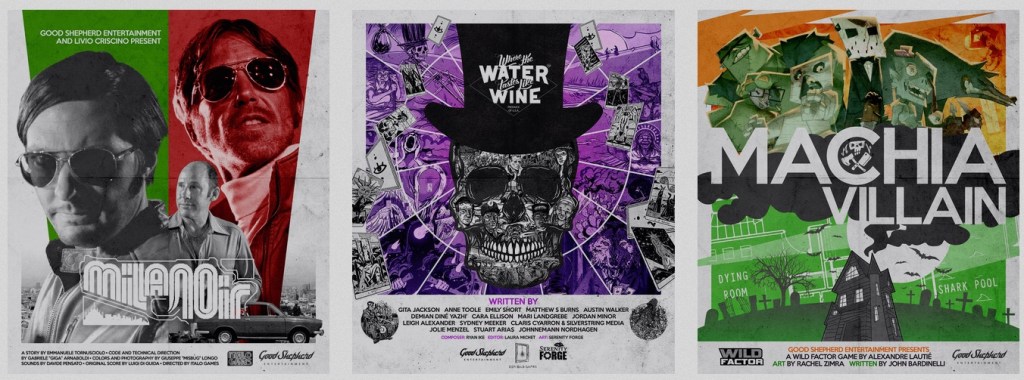

Three games currently on the roster at Good Shepherd.

The idea isn’t particularly original — it’s the kind of work that many venture funds and incubators do with young, inexperienced companies — but it hasn’t really been applied to games. Part of that is the perception that games are either hits or whiffs, making it a risky area for investment — although the same could, of course, be said of startups.

But the strategy of a huge release hopefully recouping all costs in a month or two is peculiar to AAA development; the latest Call of Duty costs a hundred million to make, so needs to sell 2 million copies before mainstream gamers move on to the next big franchise release.

An indie game doesn’t have the benefit of an Activision-size marketing team or simultaneous release in 36 countries and languages. But its budget is smaller, and people will continue buying it for years — because often the point of indie games is that they are original creations not bound to any particular console or sales cycle. Cave Story, for instance, is just as awesome today as it was in 2004 — and it still sells.

Understanding these debit and credit columns for a class of asset is critical to making a smart investment, and that’s what Good Shepherd has focused on. I talked with Mike Wilson, founder of Devolver and co-founder of Good Shepherd, while he was in town for PAX West. He said that the company is intensely focused on the writing, music, and other truly original parts of games — the kind of things people talk about for years.

“The magic of what we’ve done is to remove the ‘hit’ requirement for making investing in indie games a reasonable thing to do,” Wilson told me. “We are very sensitive to giving these people a great first experience that isn’t reliant on hitting the lottery with a project breaking into the mainstream.”

The company works with creators to fill in the gaps in their expertise, much as Devolver has done: sometimes a team needs to be connected with a good level designer, or maybe kept to deadlines, or given a hand with marketing or localization. All of a sudden a half-formed game planned for release in one country and store becomes a fully-formed one in 6 countries and multiple stores and sales. For small teams and small budgets, that could be the difference between sinking like a rock and becoming millionaires overnight — something that definitely happens now and then.

On the other side of the business, Good Shepherd is meant to be a reliable, transparent investment vehicle for people who want to back games but don’t have any idea how to go directly to creators. Acting as intermediary to investors and critical oversight for creators, the company gets to have its cake and eat it too: out one end comes money, and out the other end comes art.

Considering the pedigree of the people involved (people from the games industry who have always pushed back against AAA studios) the latter would seem to be the primary goal. If you could enable people all over the world to pursue their dreams and build something cool, wouldn’t you? Fortunately, it also happens to produce quite a bit of money, which justifies it for everyone else.

Featured Image: Good Shepherd