Google is a tech powerhouse in many categories, including advertising. Today, as part of its efforts to improve how that ad business works, it provided an annual update that details the progress it’s made to shut down some of the more nefarious aspects of it.

Using both manual reviews and machine learning, in 2018, Google said removed 2.3 billion “bad ads” that violated its policies, which at their most general forbid ads that mislead or exploit vulnerable people. Along with that, Google has been tackling the other side of the “bad ads” conundrum: pinpointing and shutting down sites that violate policies and also profit from using its ad network: Google said it removed ads from 1.5 million apps and nearly 28 million pages that violated publisher policies.

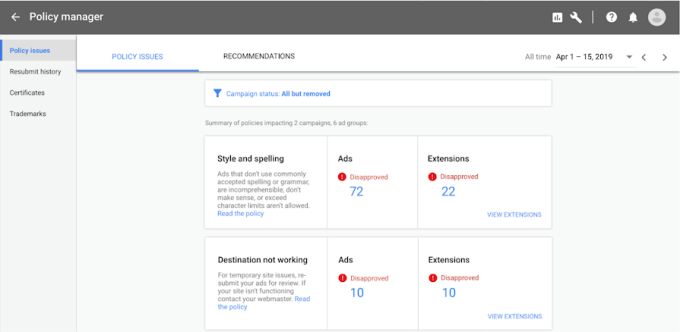

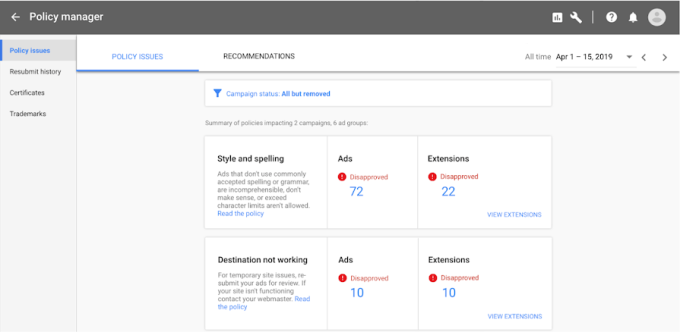

On the more proactive side, the company also said today that it is introducing a new Ad Policy Manager in April to give tips to publishers to avoid listing non-compliant ads in the first place.

Google’s ad machine makes billions for the company — more than $32 billion in the previous quarter, accounting for 83 percent of all Google’s revenues. Those revenues underpin a variety of wildly popular, free services such as Gmail, YouTube, Android and of course its search engine — but there is undoubtedly a dark side, too: bad ads that slip past the algorithms and mislead or exploit vulnerable people, and sites that exploit Google’s ad network by using it to fund the spread of misleading information, or worse.

Notably, Google’s 2.3 billion figure is nearly 1 billion less ads than it removed last year for policy violations.

While Google has continued to improve its ability to track and stop these ads before they make their way to its network, Google said in a response to TC that the lower number was actually because it has shifted its focus to removing bad accounts rather than individual bad ads — the idea being that one can be responsible for multiple bad ads.

Indeed, the number of bad accounts that got removed in 2018, nearly 1 million, was double the figure in 2017, and that would mean the bad ads are not hitting the network in the first place.

“By removing one bad account, we’re blocking someone who could potentially run thousands of bad ads,” a company spokesperson said. “This helps to address the root cause of bad ads and allows us to better protect our users.”

Meanwhile, while the ad business continues to grow, that growth has been slowing just a little in competition with other players like Facebook and Amazon.

The more cynical question one might ask here is whether Google removed less ads to improve its bottom line. But in reality, remaining vigilant about all the bad stuff is more than just Google doing the right thing. It’s been shown that some advertisers will walk away rather than be associated with nefarious or misleading content. Recent YouTube ad pulls by huge brands like AT&T, Nestle and Epic Games — after it was found that pedophiles have been lurking in the comments of YouTube videos — shows that there are still more frontiers that Google will need to tackle in the future to keep its house — and business — in order.

For now, it’s focusing on ads, apps, website pages, and the publishers who run them all.

On the advertising front, Google’s director of sustainable ads, Scott Spencer, highlighted ads removed from several specific categories this year: there were nearly 207,000 ads for ticket resellers, 531,000 ads for bail bonds and 58.8 million phishing ads taken out of the network.

Part of this was based on the company identifying and going after some of these areas, either on its own steam or because of public pressure. In one case, for ads for drug rehab clinics, the company removed all ads for these after an expose, before reintroducing them again a year later. Some 31 new policies were added in the last year to cover more categories of suspicious ads, Spencer said. One of these included cryptocurrencies: it will be interesting to see how and if this one becomes a more prominent part of the mix in the years ahead.

Because ads are like the proverbial trees falling in the forest — you have to be there to hear the sound — Google is also continuing its efforts to identify bad apps and sites that are hosting ads from its network (both the good and bad).

On the website front, it created 330 new “detection classifiers” to seek out specific pages that are violating policies. Google’s focus on page granularity is part of a bigger effort it has made to add more page-specific tools overall to its network — it also introduced page-level “auto-ads” last year — so this is about better housekeeping as it works on ways to expand its advertising business. The efforts to use this to ID “badness” at page level led Google to shut down 734,000 publishers and app developers, removing ads from 1.5 million apps and 28 million pages that violated policies.

Fake news also continues to get a name check in Google’s efforts.

The focus for both Google and Facebook in the last year has been around how its networks are used to manipulate democratic processes. No surprise there: this is an area where they have been heavily scrutinised by governments. The risk is that, if they do not demonstrate that they are not lazily allowing dodgy political ads on their network — because after all those ads do still represent ad revenues — they might find themselves in regulatory hot water, with more policies being enforced from the outside to curb their operations.

This past year, Google said that it verified 143,000 election ads in the US — it didn’t note how many it banned — and started to provide new data to people about who is really behind these ads. The same will be launched in the EU and India this year ahead of elections in those regions.

The new policies it’s introducing to improve the range of sites it indexes and helps people find are also taking shape. Some 1.2 million pages, 22,000 apps and 15,000 sites were removed from its ad network for violating policies around misrepresentative, hateful or other low-quality content. These included 74,000 pages and 190,000 ads that violated its “dangerous or derogatory” content policy.

Looking ahead, the new dashboard that Google announced it would be launching next month is a self-help tool for advertisers: using machine learning, Google will scan ads before they are uploaded to the network to determine whether they violate any policies. At launch, it will look at ads, keywords and extensions across a publisher’s account (not just the ad itself).

Over time, Google said, it will also give tips to the publishers in real time to help fix them if there are problems, along with a history of appeals and certifications.

This sounds like a great idea for ad publishers who are not in the market for peddling iffy content: more communication and quick responses are what they want so that if they do have issues, they can fix them and get the ads out the door. (And that, of course, will also help Google by ushering in more inventory, faster and with less human involvement.)

More worrying, in my opinion, is how this might get misused by bad actors. As malicious hacking has shown us, creating screens sometimes also creates a way for malicious people to figure out loopholes for bypassing them.