A few months ago, I wrote a piece about esports and the Olympics after sitting on a panel discussing whether, as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, esports had an opportunity to work with the International Olympic Committee. After careful consideration and research, my conclusion was basically, “I think that the Olympics need esports a whole lot more than esports needs the Olympics.”

I was surprised by some of the data I uncovered in the course of researching the Olympics piece, specifically on audiences for international, professional and collegiate sports. I observed that while the esports model isn’t as mature as in traditional sports, esports actually garnered close to the same level of viewership, and the audience was growing astronomically. I couldn’t help but wonder how long this phenomenon would go unacknowledged by the institutions that might benefit most from it.

Enter colleges’ and universities’ flirtation with esports: There are currently more than 170 collegiate varsity gaming programs in NCAA Division I, and the number of clubs is even higher. So even as institutions investment in esports, there are still many misunderstood and overlooked aspects of the potential to drive value (and even revenue) in the collegiate esports space.

College in the 21st century

The college experience today is very different than it was 50 years ago. The pace of change outside of institutions is ever-accelerating, often leaving colleges struggling to keep up. Technology, students’ interests, evolving economies and workplaces, and changes in cultural norms have left colleges and universities in a place of less relevance than at many points in the past.

The same can be said of college sports: Outside forces have eroded a once-near-hegemonic source of collegiate pride, cultural power, recruitment, alumni engagement and, in some cases, revenue.

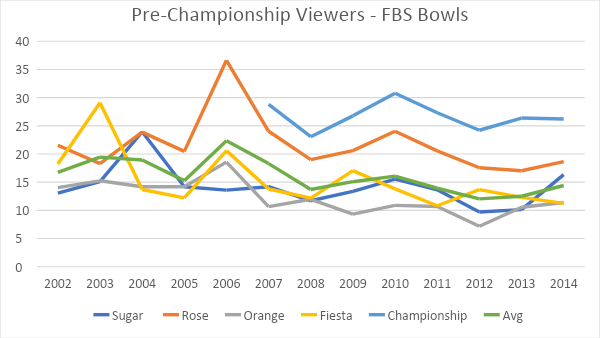

I did a quick review of the audience for the biggest NCAA events in the world; the Football Bowl Subdivision Bowl Championship and the NCAA Men’s Division I Basketball Tournament.

Image Credits: Brandon Byrne

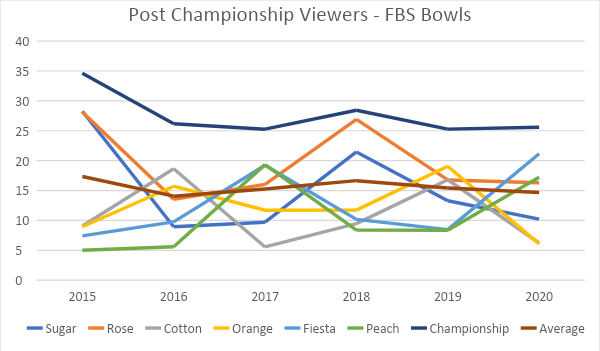

Image Credits: Brandon Byrne

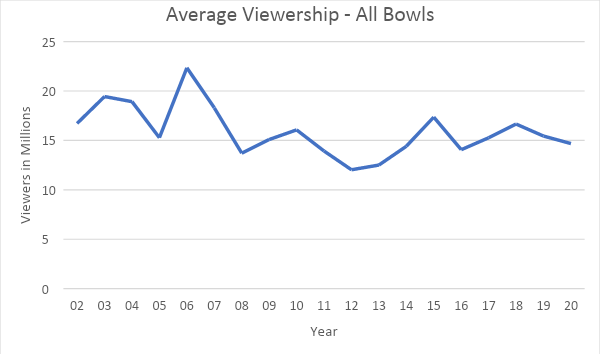

Look at the average viewership of the big bowl games before the championship system went into effect in 2015, as well as after. Above, you see the trend line for viewership for the various big bowl viewership as well as an average. While there are certainly occasional spikes, the best case you could make here is that the product is flat — when you isolate the trend line for both, here is the result:

Image Credits: Brandon Byrne

In the aggregate, the trend seems mostly downward.

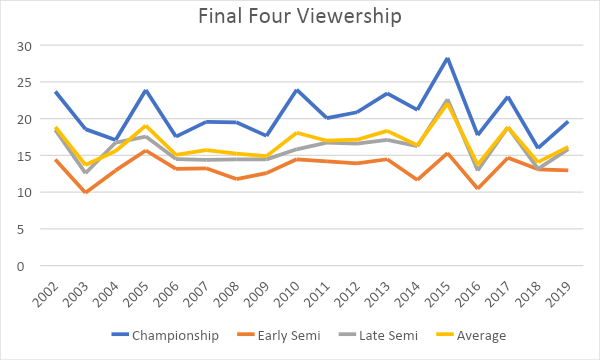

Look at the same trends in viewership for the NCAA Final Four — the early semi-final, the late semi-final and finally the championship game.

Image Credits: Brandon Byrne

They look rather similar. So, while collegiate sports still have a massive following, there are two concerning issues here. First, the audience isn’t growing at all; in fact, it appears to be slightly contracting. Secondly, the audience is aging, making collegiate sports less relevant to younger people. While an older audience is still a valuable source of alumni donations and ancillary revenue, it doesn’t exactly align with another core target demographic: potential college students.

Now despite this, there is data that suggests that schools with elite academic departments do enjoy a phenomenon known as the “Flutie effect,” named after Doug Flutie, a quarterback for Boston College whose exciting performance on the gridiron was credited with boosting BC applications. An article in Forbes breaking down an HBS study goes into the phenomenon more deeply than we can here.

Granted, much of the data is from a few years ago, when college sports were perhaps more relevant, but the point is broadly the same: Having an elite program in an activity students enjoy benefits the institutions that sponsor and promote them. But what happens when enthusiasm for those activities among the student body is waning? One idea is to explore involvement in what the students of today are interested in.

As a comparison to FBS football (maxed out at 35 million viewers) and the NCAA Final Four (maxed out at 28 million), Riot Games’ Mid-Season Invitational event for League of Legends had a total viewership of 60 million people. In second place is the Intel Extreme Masters tournament in Katowice with 46 million people. While precise demographic data isn’t readily available, it stands to reason that the latter two events skew younger than the former two.

A few caveats, as these are not precisely apples-to-apples comparisons: These esports events are broken up over a number of days and encompass a significant number of matches — comparable to March Madness, perhaps — and the content is consumed in different ways. Much of the NCAA’s content is presented on television, some of which is on paid, premium channels. Esports events are broadcast on Twitch and YouTube via streams for free.

But the thing to understand is that esports audiences are growing at a 15%-16% year-over-year clip and it commands a worldwide audience, meaning its total addressable market (TAM) is MUCH bigger. The NCAA events are not likely to draw serious audiences outside of North America.

COVID-19

In the context of the pandemic, colleges are hamstrung by students’ inability to engage in a college experience in-person, which is one of the primary reasons one goes to college. Networking, developing new friends and having new experiences are all a part of the collegiate draw, none of which work as well from students’ parents’ living rooms. Similarly, collegiate sports as we know them have essentially ceased to exist, along with their functions of institutional pride, marketing and revenue. The NCAA Tournament was canceled in March of 2020 and there is no sign that it, or any other sport, will be back anytime soon.

Esports, on the other hand, are thriving in this context, thanks mostly to their ability to offer remote competition and viewing. Esports tournaments can isolate audiences, teams and even referees to allow for safe content creation and consumption.

Esports and college

Believe it or not, esports is a better fit for college than it is for the pros. I won’t go into all of the details here, but I actually wrote a separate article about why the pro sports model is NOT a good one for esports. In this article we talk about intellectual property, who owns the league in esports and how all of the entities make money. The biggest problem is, in pro sports, the teams own the league and can then act in the best interest of all of the teams. In esports, the league is usually owned or regulated by the publisher of the video game, meaning you have hands in the monetization pie in a way that pro sports doesn’t have.

The interesting thing about this is that college athletics actually has the same problem and has found a way to mitigate that. The athletes get their scholarships, and the schools, their athletic conference, and the NCAA itself all own a piece of the pie that gets packaged and sold for distribution to the ESPNs and Fox Sports of the world.

This is a much better model for esports. It’s unlikely that any group that “owned” football IP would tell the Dallas Cowboys how to market their team, what their cut is and how it will be distributed. This process happens all the time in college, though. In fact, in order for everyone to get their seat at the table, you HAVE to work all of this out so that the schools make some money (equivalent to a team), the conference makes their money (equivalent to the league) and the NCAA makes their money (equivalent to the publisher themselves). If the chain breaks down at any point, then the whole process grinds to a halt and nobody makes money.

I mention this in my article about the Olympics. The IOC is used to having full autonomy over how the Olympic Games are broadcast, which events are part of the games, who is eligible and who isn’t, etc. There is no chance this would be the case if the Olympics took on esports. The publisher would absolutely wield an incredible amount of influence over how the games are portrayed, broadcast, judged and the like. The IOC isn’t used to that. In college, that’s just a typical Saturday afternoon.

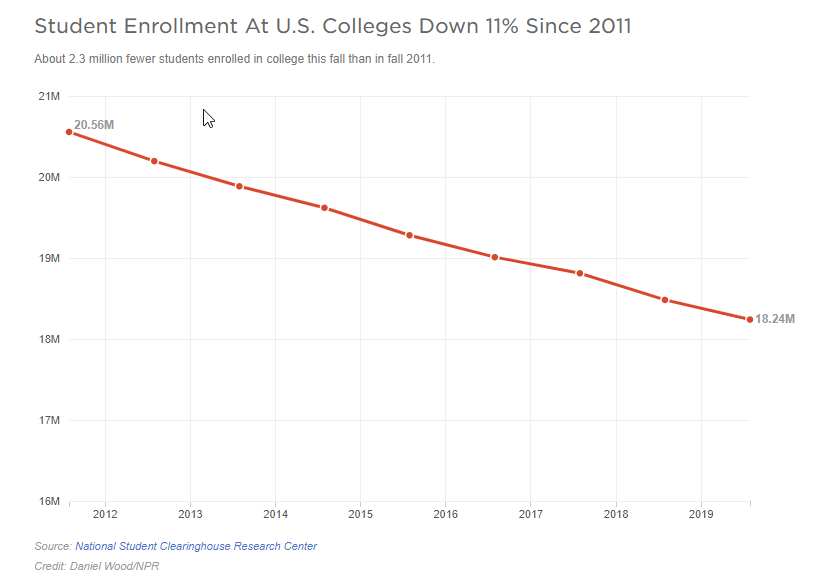

College admission is down and not just because of COVID-19. Even before the pandemic, colleges were trying to find their footing with potential students as people reevaluate the college experience. Forbes wrote back in 2019 that college enrollments were down two million students in that decade. Add onto that the preliminary data we are getting on the effect of COVID on colleges, we could see enrollment in 2020 down anywhere from 5%-20%.

Image Credits: Brandon Byrne

The outlook

For colleges, it’s not great. Revenue is massively down, with even stalwarts like Harvard University hemorrhaging cash. With enrollment down before the pandemic, we have reached a point where colleges and universities have to adapt to survive.

The good news is, I believe that esports could be an opportunity to do just that. Colleges are diving into esports, with 115 different programs offering scholarships for esports and club programs are growing even faster. Certainly, it will help attract students, but monetization in esports is really tricky.

It’s critical that colleges and universities get expert advice on how to create an ecosystem that ultimately compensates all of the stakeholders, including the college themselves. It also will require universities to move quickly and get on board with a model that is still being formed in real time. The coronavirus pandemic isn’t going away anytime soon, but I think there will be many colleges that will. The time to move is now.