![]()

One of the big stories in the camera industry so far this year has been the bankruptcy of net SE, the German company behind the revival of classic lenses that raised millions of dollars through crowdfunding services such as Kickstarter.

Around the time of its bankruptcy filing, net SE also announced that its founder and CEO, Dr. Stefan Immes, had gotten seriously injured in a car accident and would no longer be able to run the company.

Given the enormous sums of money net SE managed to haul in through crowdfunding from thousands of photographers around the world, news of the company’s financial failure undoubtedly came as a shock to many backers. net SE had the appearance of growth and success through its famous brand names and popular Kickstarter efforts, but behind-the-scenes things were anything but healthy.

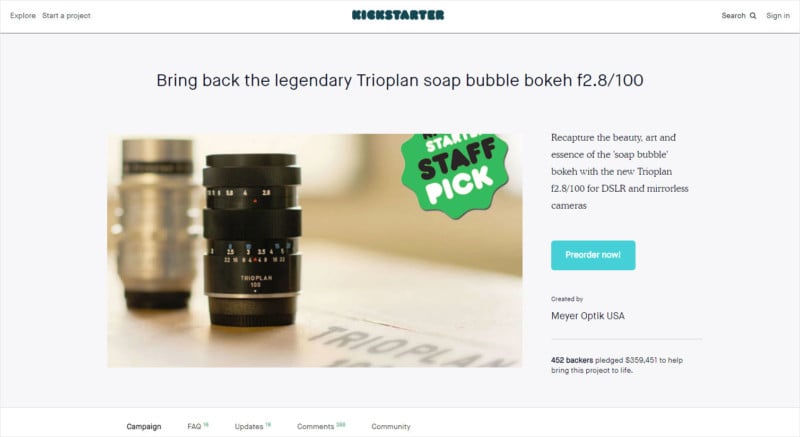

Geoff Livingston, a marketer and the founder of Livingston Campaigns, joined Meyer Optik Görlitz as a contractor in 2016 and ran the brand’s Trioplan 50 Kickstarter campaign, which raised $683,801, before departing later that same year. Although his stint was brief, Livingston says he noticed warning signs early on.

“The first was launching the Trioplan 50 Kickstarter even though the last Trioplan 100 orders from the prior year’s Kickstarter were just shipping,” Livingston tells PetaPixel. “This was against strong counsel from both me and several employees inside.

“We literally were dealing with complaints about not receiving the 100 while pushing the 50. Not ideal from a PR perspective, but we were told that the company had to launch the Kickstarter. I think the campaign suffered a bit from that.”

“The second red flag was launching the Primoplan Kickstarter so soon after the Trioplan 50,” Livingston says. “It was super aggressive for a company that had struggled to fulfill its first Kickstarter and had yet to fulfill the second. Again, it was against counsel, but achieving scale was the logic presented for going with the Primoplan Kickstarter in September 2016. By then I had left.”

Joe Newman, the executive director of the D.C.-based non-profit Focus on the Story, was contracted to replace Livingston and handled the brand’s marketing from September 2016 through January 2018. Like Livingston, Newman also became alarmed at net SE’s aggressiveness in pushing new Kickstarter campaigns before the dust had settled on previous ones. And what’s more, it seemed that net SE was using new Kickstarter campaigns to fund finished ones.

“At some point, we were preparing Kickstarter campaigns before the current ones had even ended,” Newman says. “I want to stress that I never saw their books and had little to no knowledge of their overall budget and financial health. But it was apparent that the Kickstarter campaigns were viewed as a way to raise operating funds, not for the upcoming lens, but for the ones already in the production pipeline. […]

“[T]hey just didn’t seem to have to the capital to ramp up production to keep up with the demand they were creating.”

The “smart” thing net SE could have done would have been to raise money from an outside investor, Newman and Livingston say, but instead the company continued to drink from the Kickstarter well and risk individual photographers’ money instead of larger investors’.

Newman says the company soon began “throwing ideas up against the wall to see what would stick.” net SE started introducing new lenses under new “shell companies” by registering the names of other old German lens companies that had gone out of business decades ago.

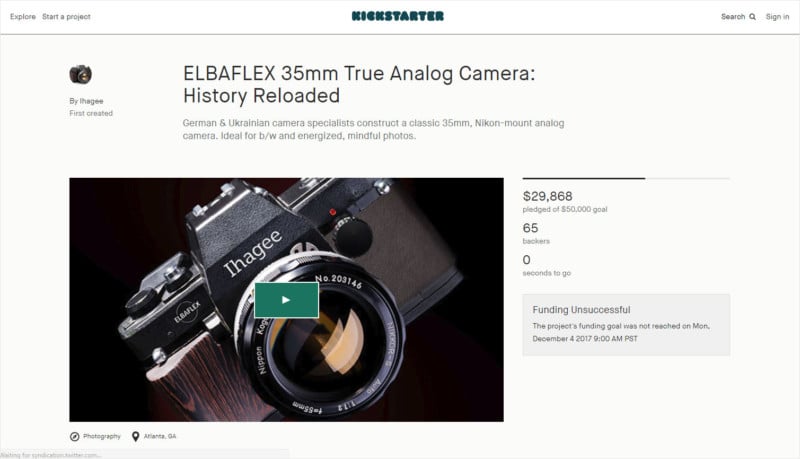

Other historical brands net SE attempted to reboot include Emil Busch A.-G. Rathenau, Oprema Jena, C.P. Goerz, Ihagee Elbaflex and A. Schacht.

![]()

“What was ridiculous was that they wanted to pretend that these new brands had nothing to do with Meyer Optik,” Newman states. “Dr. Immes reasoned that he wanted to maintain the Meyer Optik brand as lenses made by hand in Germany. […] I could buy that argument but I told him flatly that everyone knew that as soon as the Kickstarter project was announced that it was by the same people behind Meyer Optik, especially when the press releases were coming from the same person (me) who was handling Meyer campaigns.

“He responded that couldn’t we say that they had introduced the people behind these news lenses to me?”

We reached out to net SE for comment regarding this story but have yet to hear back.

And when Kickstarter told net SE that it wanted the finished Meyer Optik campaigns fulfilled before starting new ones, net SE soon turned to Indiegogo.

![]()

While many photographers believed that Meyer Optik Görlitz was a larger company with many employees and vast production capabilities, in reality it was a tiny operation with only a handful of people.

“A lot of the Meyer Optik persona was smoke and mirrors to some extent,” Newman says. “The upper management team was really only three people as far as I could tell. […] I’m not sure how big the production facility was but at one time, they told me they could produce about 30 lenses by hand in a day, so that gives you some idea of how big they were.

“They priced their lenses to compete with the big players but they were way out of their league. It actually took me a while to figure that out.”

Meyer Optik Görlitz eventually got its products listed by the New York camera superstore B&H but the trickle of lenses leaving the production line meant that the products were almost always listed as back ordered.

Despite net SE’s questionable business practices, both Livingston and Newman believe that the company was actually operating in good faith and was working hard to deliver on its promised lenses.

“I really think it was a case of them just being in over their heads as opposed to being out to scam people,” Newman says. “They wanted to look like a big player but they were just a small operation trying to punch way above their weight. I think Immes got blinded by his early success on Kickstarter and was thinking that one big viral hit was just around the corner.

“It’s a shame because the story of Meyer Optik could have turned out a lot different.”

The business model proved to be unsustainable — hence the bankruptcy — and now both Livingston and Newman are doubtful that photographers who backed the projects will ever receive the lenses they gave money for.