![]()

Deep Sky West is a remote astrophotography observatory in New Mexico, USA. It offers the opportunity for any astrophotographer around the world to use the site to access clear skies without the need to travel there, and to use advanced astronomy and photography equipment without the need to own it themselves.

I talked to Lloyd L. Smith, co-founder of Deep Sky West to find out more about how they built Deep Sky West, how you can use the observatory, and to get his advice on how to build your own.

What is Deep Sky West?

DSW is a remote astrophotography observatory. That is, it’s a site that holds advanced telescopes, cameras and all the equipment needed for deep sky imaging under a rain-detecting retractable roof that can all be controlled without the need for anybody to be there in person (although there are 3 technical support personnel).

This means that photographers from around the world can get involved and use the site to host their own equipment, and/or the equipment there to target specific objects in space and have the data gathered sent to them for post-processing to create astronomy images.

This video gives you a good idea of what the observatory looked like when it opened in August 2015. The drone approached the property from due north. The white observatory building can be seen in the distance and the green roof of the underground residence can be seen at lower right as the scene unfolds:

The observatory in the video has since been doubled in capacity (the structure is modular). The sister observatory, DSW “Beta” will be operational in September 2018.

Where is it?

It’s situated on Glorietta Mesa in Rowe, New Mexico.

It’s at high altitude (7,400 feet elevation), and its location away from the light pollution of cities offers dark skies and good weather conditions that hard to find for many (most?) astrophotographers around the world.

As the Deep Sky West co-founders say, their observatory “is for the average backyard astrophotographer who has a love for the hobby, sometimes has great equipment, but is plagued by poor skies.”

How did the idea come about?

Two guys – Bruce Wright and Lloyd Smith – came up with the idea for Deep Sky West on New Year’s Eve 2014.

Bruce had a life-long dream of building an energy-efficient, off-the-grid home and had succeeded in this by building an underground house on a 35-acre plot of land in New Mexico.

But that day at the end of 2014, Bruce and Lloyd were looking up and saw that “the most incredibly transparent sky encircled us from horizon to horizon”.

They decided then that it was the perfect location for an astrophotography observatory and set in motion the plan to build Deep Sky West.

In June 2015, the first version – named DSW Alpha – was completed and fully operational.

How does Deep Sky West work?

DSW Alpha is a ”Roll Off Building” (ROB) observatory. That is, the building literally rolls on and off the grid of telescopes according to when it is being used, or when it needs to be closed. It is a steel construction that runs on rails similar in design to a rollercoaster.

The building is “captured” both above and below tubular rails and is thus able to withstand high winds. A custom designed electric motor and gearing enables the 2.5-ton structure to be moved with ease.

To help you picture it, Lloyd says, “a common garden shed outfitted with wheels would make a fine observatory!”.

DSW Alpha started as a 25 x 30 foot, 9-pier facility but the modularity of steel construction allowed them to add more roof sections as needed. There is now an additional 25 feet of roof and 9 more piers, which were installed in summer 2016. They now refer to the upgraded facilities as Alpha 2.0.

A second observatory is underway and expected to be completed by September 2018. It’s called, wait for it, DSW Beta, which follows the same basic design.

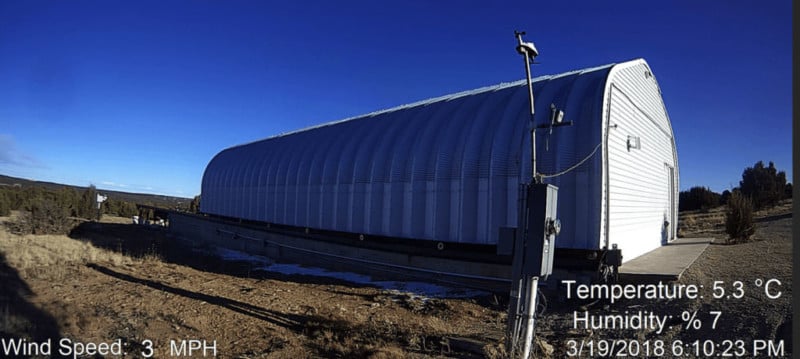

A construction camera can be seen live which is documenting everything for a time lapse to be produced when construction is completed.

The design

A number of other design elements play a critical role in the effectiveness of a roll-off building:

First is overhead clearance.

DSW’s overhead clearance is 9.5 feet and all imaging systems are kept below this level so that contact between any equipment and the roof is impossible.

When weather conditions demand, the observatory can close without regard for the position of any system. “There’s no need for special “at park” sensors or anything similar. When it’s time to close, we close.”

The second design element is the inner stub wall system.

This provides protection from ground-level dust and other unwanted elements. They give the feel of a traditional roll-off roof but are stationary and non-load bearing.

The stub walls are convenient for power outlets, flat panels, etc. Some traditional ROBs go so far as to motorize the southern wall to increase visibility to the south. At Deep Sky West they just limited the southern wall to 4 feet – “southern views go down to the horizon if you want to chase a southerly target” and does not require any additional automation.

Redundancy is another important element.

Every critical subsystem has a backup – especially cloud and rain sensing. They use two Sky Alert cloud sensing systems with automatic failover and employ Hydreon optical rain sensors in a redundant arrangement to provide additional rain sensing capability.

A Davis Weather Station supplies micro-climate information to the roof actuation system. “In all, there are 5 systems that monitor the weather and work together to determine whether or not conditions are safe.”

Lastly, Power is a critical subsystem.

Their UPS (backup power system using charge-managed deep cycle marine batteries) has the ability to operate the roof and run the imaging systems for several days. However, to continue to operate on UPS power without knowing the cause of a power outage is unsafe and so if the main AC fails, they close and stay closed until they understand the reasons for the failure.

Lloyd says “Equipment and infrastructure protection is our primary concern. We’d rather miss a few hours of clear sky before risking the safety of the facility and its contents. As such, we take a conservative approach with respect to observatory opening and closing. DSW is fully autonomous and opens and closes based on inputs from all the various sensing systems. Redundancy and strict adherence to protocol protect the observatory.”

When does the roof open up?

The normal open and close cycle for DSW is to open every day one hour before dusk and to close 30 minutes after sunrise.

The time between opening and astronomical dusk allows the systems time to reach thermal equilibrium and to perform other functions like flat acquisition.

The protocol for opening and closing depends on several factors: Deep Sky West opens at the appointed time only if main AC power is active, WAN/LAN is functioning, and the weather is clear.

The definition of “clear” is a function of the difference between the ambient temperature and the sky temperature. The latter is measured by infrared sensors on the Sky Alert system.

If “clear” is detected and all other conditions are met, then the observatory opens for business. The operators, technicians, and residents are notified via email and/or text messages anytime the roof opens or closes and the reason for the movement.

Lloyd says, “our favorite message is “Email #1 – DSW1 – Opening Beginning of Session”. Conversely, our least favorite message is “Email #9 – DSW1 – Not Opening at Sunset Due to Weather”. This disappointment is easily reversed when we receive “Email #8 – DSW1 – Re-Opening After Weather Event”.”

All observatories require technical support whether they’re in a backyard or far from home but remote observatories present a particular challenge for the obvious reasons: you can’t touch your system and depending on the infrastructure you might not even be able to see it.

Therefore, competent, local support is critical. Well-designed redundant systems help tremendously, but nothing replaces real human interaction. At Deep Sky West they have several support personnel with various areas of expertise including infrastructure, network and imaging system operations.

This video shows a timelapse of Deep Sky West over a period of 24 hours:

Who can use the remote facilities?

The tagline of Deep Sky West is “remote Imaging for the Rest of Us”.

Lloyd says, “our primary goal is to make remote, dark site imaging affordable and attainable for the beginner astrophotographer to the most ardent amateurs and even professionals. There’s no need to re-invent the wheel since we’ve already procured a site, implemented the infrastructure, built the observatory, and hired on-site support. Affordable remote imaging, every clear night, is within your grasp—no building, no driving, no sleepless nights, no hourly points systems, no creepy crawlers and no wasted trips!”

“The lack of consistent clear skies results in equipment going idle for long periods. When the weather does cooperate many imagers have to travel to remote locations, set up equipment from scratch, polar align, image (if the weather holds up), and tear it all down again at the end of the session. Astrophotographers fortunate enough to have a home observatory don’t have the hassles of setting up for each session, but many locations still lack quality skies.”

Lloyd adds, “Whether you’re a seasoned imager or just starting out in the hobby you’ve realized a few fundamental facts about our shared pursuit: 1) it’s really hard and 2) it can be very expensive.”

How can photographers get involved in Deep Sky West?

There are two ways you can utilize Deep Sky West:

1. Rent a space and use your own equipment

This is the traditional approach, wherein an imager leases a pier and operates their own system remotely.

This is remote imaging in the “classic” sense: you operate your equipment as you see fit, perhaps you work with a small group of friends and you split expenses—this is up to the team. In this model, individuals can host their own systems for an all-inclusive monthly fee of $700.

Alternatively, like-minded individuals can pool their equipment, financial and knowledge resources to create a small team. They help team founders to find other team members throughout their network and the astrophotography community in general.

For example, one Deep Sky West imaging team uses a TEC 160 (a $12,500 telescope) owned by a member/founder from Texas with team members from Italy, Australia, and China. This team splits the pier lease costs and all data is shared equally across their small group.

Observatory personnel are available to perform system installations if the equipment owners can’t make the trip – a process that typically requires 2-3 clear nights to complete. This includes the physical installation, network set-up, polar alignment, and calibrations as required (focuser, PEC, rotator, collimation, etc.)

If people perform to do their own installation, Deep Sky West personnel are on site to provide assistance. As a bonus, they also provide lodging at the residence free of charge!

2. Sign up to join a Deep Sky West-operated team and use equipment already there

The other model is a virtual team shared system concept and is the easiest way to start remote imaging at the observatory.

How it works is that imagers from around the world select to receive data from any of our 6 Deep Sky West-operated systems. The members then receive all the data collected on the system(s) of their choice. “It’s like a data subscription service”, says Lloyd.

The teams operate very simply: general imaging standards are set for exposure times and binning, all members participate in a democratic target selection process, and all data is shared equally among the team members. The final images belong to the processor. The cost is from $600 per year.

Controversy: Who is or isn’t an astrophotographer?

This second model has generated some controversy as some claim that the photographers are not taking the pictures themselves and therefore is not “real” astrophotography.

Lloyd says, “there’s a school of thought that says in order to be considered a real astrophotographer one must perform their own data acquisition and image processing. It’s the collection part that seems to be at the center of the issue. Clearly, our shared-system model removes the data acquisition part of the equation, but the processing is left up to the member.”

“Our position is clear: if you don’t have the equipment, skills or skies you should not be denied the opportunity to participate in this wonderful hobby at a reasonable cost. We also believe working within a community of similar imagers significantly enhances the experience and accelerates the learning process. We don’t judge who is or isn’t an astrophotographer.”

They also allow those with “interesting systems which are desirable to other imagers” to be hosted for free.

Lloyd says, “it’s a play on the sharing economy in a way. The sky isn’t going to change substantively in our lifetimes, but the equipment is changing quickly and not everyone can afford to get the latest greatest thing all the time.”

What equipment does Deep Sky West offer?

Today the Deep Sky West equipment available includes:

- A Rokinon 130mm wide field lens

- A Takahashi FSQ telescope

- Two difficult to get Astro-Physics 305mm F/3.8 Riccardi-Honders Astrographs (with 16803 and 8300 chips)

- An RCOS Carbon Truss 14.5 inch Ritchey-Chrétien Telescope (3,360mm FL)

- An Astro-Physics 175 mm f/8 Starfire EDF refractor—another rare instrument

“We don’t own all these systems,” Lloyd says. “Some are owned by our members who, in exchange for hosting and support, allow us to open the systems to other members via our shared model. Each of these is interesting in its own way and we’re happy to have them on offer for imagers who’d like to participate in this way.

“Ours is similar to other services, but we believe we’ve made it more cost-effective and our members are able to work with data integrations of at least 15 hours per target. This varies by instrument, but our goal is quality of images over quantity.”

How to build a remote astrophotography observatory yourself

Having successfully built Deep Sky West, the co-founders can offer some great insights and expertise to anyone else interested in building their own.

They recommend that the below equipment is needed:

- A small refractor telescope (300-600mm focal length)

- A quality mount similar to A-P Mach1GTO, Paramount MyT, 10Micron 1000HPS

- A sturdy pier or tripod

- A quality CCD camera with in-country support

- A Windows 7 computer with adequate storage and 8G of RAM

- A Digital Loggers IP Power Switch for remote power control

- ACP, CCD Autopilot, or similar for automated imaging

- A webcam so you can see what’s happening

- SkyAlert or Boltwood for cloud sensing

- SkyEye for all-sky cameras

- SkyRoof for dome/roof control

- A Hydreon optical rain sensor for backup to your cloud-sensing system

- A Davis weather station for local micro-climate information (can be used for dome control, but is often used just for local weather information)

- A robust UPS for dedicated dome/roof closure.

They also recommend cloud-managed network devices (Cisco Meraki, for example) and a cloud service for data storage and retrieval (Google Drive, Dropbox).

They also stress the importance of devising roof/dome closure protocols – I.E., what to do on power failure? Run on UPS or close until the source of failure is understood and corrected? What to do after a period of bad weather? Re-open or stay closed for the night?

Lloyd says they are also happy to talk to anyone seriously thinking about building their own remote observatory, “we’re also glad to consult with you with no obligation…just paying it forward.”

Further information about Deep Sky West

“When I first started in astrophotography I read everything I could find,” Lloyd says. “The main messages I heard were: ‘this is really hard’, ‘you need specialized equipment’ and ‘it’s very expensive’. I fundamentally understood all these things, but hey, I had an SCT, a basic GEM, and a good film DSLR. And I had the desire to produce images like the ones in the magazines. Surely I could make this happen if I were very careful and, of course, smarter than the average bear.

“Before any debate gets started let me say that there are imagers who could do a great job with the equipment that I had—I’m just not one of them. I struggled and eventually gave up except for the occasional looks at the moon and planets. Ten years went by and I finally got the message and upgraded my equipment (to an FSQ-106, Mach1GTO, and QSI583).”

He says the first key learning point was to get the right tools.

“I finally had reliable, quality equipment, but didn’t have the first clue on how to do a plate solve, or what the heck I was supposed to do with a V-Curve. Slowly, but surely I figured it all out in my backyard.”

His second key learning: “go remote from home first.” He says he was lucky he had resources and good skies available to him. “Without access to skies or equipment your options are severely limited.”

“Deep Sky West offers a way around some of these limitations. Many would-be imagers don’t have the resources to spend on equipment and image acquisition which is only part the battle. Processing is an art and science unto itself. Quality data is critical to learning the techniques. Deep Sky West solves the data acquisition hurdle and allows entry into the hobby for those who otherwise not get involved in the first place. We also provide an affordable dark site for imagers further along the continuum. In fact, the typical arc for our members is to start out on one of our systems, perhaps step up to one of our longer focal length instruments and eventually automate their own local systems or host with us.”

What’s the future for Deep Sky West?

“As for DSW, this is a labor of love. Of course, we are a small business, but both Bruce Wright and I, the co-founders, have successful careers in the consulting world. Our client service experience in working with Fortune 500 companies informs our approach to business and customer service.”

“We built DSW out of intellectual curiosity and the desire to build something different. DSW is debt free and completely owned, operated and fully funded by the two of us—friends of 30+ years. In other words, we’re like an old married couple! We debate and deliberate, fuss and fight a bit, but we find common ground and we act in the best interests of our members. As long as imagers demand affordable, dark skies we’ll keep doing what we’re doing and adapting as our members’ needs change. Good luck and clear skies!”

More information on Deep Sky West can be found on their website.

About the author: Anthony Wallace is the editor-in-chief of Skies & Scopes, a website for astrophotographers, astronomers and stargazers. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. You can read more articles by Wallace on his website. This article was also published here.