What if you could look down and see your actual arms and legs inside VR, or look at other real-world people or objects as if you weren’t wearing a headset?

The team at Imverse spent five years building this incredible technology at EPFL, the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology of Lausanne. “We were working on this before Oculus was even created,” says co-founder Javier Bello Ruiz. Now its real-time mixed reality engine is ready for public demos, debuting this month at Sundance Film Festival.

Imverse‘s tech has the power to make VR seem much more believable and easy to adjust to — which is critical as the industry tries to grow headset ownership amongst mainstream buyers. The startup wants to become a foundational software platform for the development experiences, like Unity or Unreal. But even if their commercialization stumbles, one of the VR giants would probably love to buy Imverse’s tech.

Below you can see my demo video of Imverse’s mixed reality engine from Sundance 2018:

While there’s certainly some pixelation, rough edges and moments when the rendered image is inaccurate, Imverse is still able to deliver the sensation of your real body existing in VR. It also offers the bonus ability to render other objects, including people, allowing Bello Ruiz to shake my hand while he’s in a VR headset and I’m not. That could be helpful for bringing VR into homes where family members might need to share the living room without knocking into people or things, especially if someone’s trying to get your attention when you have a headset and headphones on.

The first experience built with the real-time rendering is Elastic Time, which lets you play with a tiny black hole. Pull it in close to your body, and you’ll see your limbs bent and sucked into the abyss. Throw it over to a pre-recorded professor talking about space/time phenomena, and his image and voice get warped. And as a trippy finale, you’re removed from your body so you can watch the scene unfold from the third-person as the rendering of your real body is engulfed and spat out of the black hole.

“This collaboration came out of an artist residency I did at the lab of cognitive neuroscience in Switzerland,” says Mark Boulos, the artist behind the project. “They had developed their tech to use in their experiments and neuroprosthesis.”

Imverse’s volumetric rendering engine both detects your position while also capturing what you look like so that can be displayed in VR

Between microfluidic haptic gloves that let you feel virtual objects and sense heat, and the psychedelic experiences like Requiem for a Dream director Darren Aronofsky’s galaxy tour Spheres, there was plenty to wow VR fans at Sundance. Yet Imverse is what stuck with me. It unlocks a new level of presence, which every VR experience and gadget aspires to. Actually seeing your own skin and clothes within VR is a huge step up from floating representations of hand controllers or trackers that merely show where you are. You feel like a full human being rather than a disembodied head.

That’s why it’s so impressive that the Imverse team has just four core members and has only raised $400,000. It got a huge head start because CTO Robin Mange has been specializing in volumetric rendering for 12 years. Bello Ruiz explains that Imverse’s tech is “probably his fifth or sixth graphics engine he’s created,” and that Mange had been trying to build a photorealistic environment for neurological experiments with Bruno Herbelin at EPFL’s Laboratory Of Cognitive Neuroscience, but wanted to add perception of one’s own body.

Imverse is now working on raising a few million dollars in a Series A to fund a presence in Los Angeles where it’s working with content studios like Emblematic Group. Bello Ruiz says that would solve one of the startup’s main challenges, which is that in Switzerland, “you have to first convince people that VR is important, and then that our technology is better.”

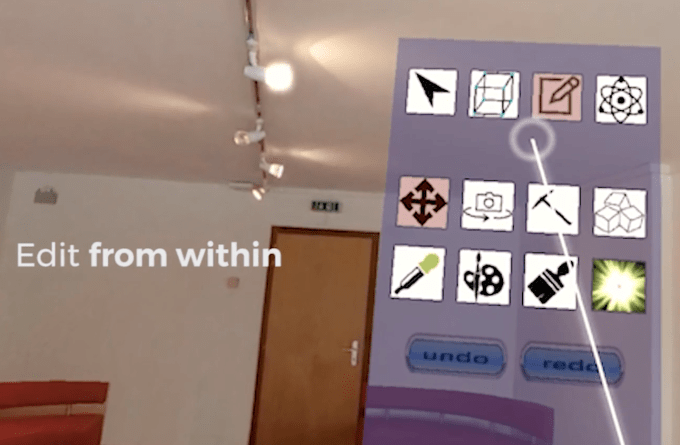

In the meantime, Imverse is developing LiveMaker, which Bello Ruiz calls a “Photoshop for VR” that offers a floating toolbox you can use to edit and create virtual experiences from inside the headset. He says film studios could use it to make VR cinema, but it could also help out marketers, real estate companies or even do mathematical simulations. Imverse’s previous work allowed a single 360 photo to be turned into a VR model of a space that could be explored or altered.

Imverse’s “LiveMaker” is like a Photoshop for VR

There’s plenty of room for Imverse to make its mixed reality engine clearer and less choppy. The drifting pixels can make it feel like you’ve been haphazardly cut out and stuck into VR. Yet it still gave me a sense of place, like I was just in a different real world with my body intact rather than in an entirely make-believe existence. That could be key to VR fulfilling its destiny as an empathy machine, allowing us to absorb someone else’s perspective by acting out their life in our own skin.