![]()

Is the most egalitarian form of photography, ‘street photography’, being destroyed by its own popularity? Is such a thing even possible? I won’t profess to have a clear answer to this question, but I do have some thoughts. Those thoughts may turn into a rant, but I’ll try to contain myself!

Egalitarian = good, right?

This question hits right at the heart of photography and, most specifically, digital photography. If something is easy, more people will do it. The more people doing it, the more ‘cultivated talent’ there will be (which is a good thing). However, there can be a cost: the dross can become overwhelming.

Street photography is easy for everyone to engage in. If you have a camera and are able to access public areas, you can shoot street photography. While this sounds great, I can’t help but feel something of a massacre is taking place. Cameras have become optical machine guns, mowing down everyone and everything with carefree abandon.

The problem, as I see it, is exacerbated by a particular catalyst: for want of a better word, it is ‘cool’. When something is fashionable in this way, the self-image can become the real target, rather than the photograph itself.

So what has ‘coolness’ done for street photography?

It has clouded judgment, that’s what it has done. Some photographers evidently struggle to see past their excitement at indulging in this fountain of cool. Twenty years ago, to pull this off, you had to tote a film camera around and go through all the palava of changing rolls, developing them, faffing with lightboxes, checking contact sheets and making prints. If a person was prepared to go through all of this inglorious hassle, there was a very good chance they were reaching a bit deeper, within and without.

Now, in the digital age, you can buy the right ‘stealth satchel’, blaze away and saturate Instagram and Flickr within hours. At no point in this process will you have to consider the merits of the photographs being taken, because it doesn’t matter. You’re a rock and roll street sniper. At least a landscape photographer has to deal with bad weather, muddy feet and uncooperative light to get his or her shots and that obstacle of effort acts as a filter.

When it’s raining, the street ninja just slides into Starbucks and takes 482 photographs of coffee cups, tables, people’s feet, the window, people walking past the window, people tying their shoe laces… and they’re all painfully boring. Sadly, this garbage is overflowing into the street so to speak. The visible face of popular photography is more and more being defined by street photography, when we’re not being overwhelmed by photos of people’s dinner on social media.

Why could this be bad?

The good street photography is being buried, that’s why. It is more difficult than it should be to find consistently good street photography taken by someone without an already well-known name. The work is out there, I have no doubt of that, but the process of finding it is exhausting and depressing. There also seems to be a bit too much ego in the mix. Far too many of these (often very young) photographers seem unwilling to learn. They’re already amazing, which they know, because that’s what they tell each other continuously on social media. They also have lots of ‘likes’, so that’s that.

On the occasions when I have seen really good photographs on Instagram/Facebook groups, the inspiring work barely gets a mention. Nobody cares. That’s not what social media is about and street photography has become the social media of photography: an avalanche of banal, shallow and unreflective nothing that hasn’t the time to consider its own context. Tell a lie often enough and it becomes the truth. In the same way, much of this ‘great street photography’ is, well, the new great.

Editing. What is that?

Too many street photographers don’t edit. They share everything, perhaps because they think the world wants to know what fifty different takes of groups of random people walking down the street looks like at 8:56 in the morning, on their way into work. I applaud the enthusiasm, but photography is like selling your house. You show the best bits, while trying to avoid scrutiny of the bad bits.

You put your junk into the loft, or carefully pack cupboards. You mow the lawn, give a lick of paint to that beautiful front door and make sure your new kitchen is sparkling. The whole point is to draw attention to the good bits and let them define your house as a proposition. You curate the impression you want to leave people with. What you don’t do is give them a guided tour of the junk pile corner of your garden, the rotten window frame you’ve meant to replace and then hand them a map of the broken floor tiles.

When you’re Magnum Photos, you can put out a book full of contact sheets when most of the photographers who took those hugely iconic images are dead! Everyone else is better off editing at least until it hurts.

Endless juxtapositions and their formulaic brethren

Visual juxtapositions are akin to a trick that can be performed according to recipe. They are cookie cutter photographs that deliver all of their impact (if they have any at all) in no more time than it takes to mentally identify the game. A boot on a poster steps on a passing pedestrian’s head. The man standing at a bus stop is being shouted at by a woman on a billboard.

See, you didn’t even need a photo to experience all that such photographs contain: a simple, boring, endlessly repeated ‘jingle’. You could only ever write one short line about such photographs, because they contain nothing beyond the superficial.

Some photographers have built entire series (in fact entire websites) crammed full of variations of the same thing. They’re no more interesting than ‘zonies’ obsessed with Ansel Adams’ Zone System, who 20 years ago produced endless photographs of tree stumps and sticks that showed how wonderfully they’d applied -3 compensation development. My personal hit list goes something like this:

Juxtapositions. If they say nothing and have no appeal beyond their initial visual recognition, they’re boring. Really boring. Even the ‘good ones’.

Random photos of nothing, for no reason, with no content, thought, insight or anything. They’re not so casual as to be cool. They’re just boring.

Faux edginess. People being made to look mean, when they aren’t. Intensity that has been added in Photoshop, or with a pithy title that over-eggs the pudding. Their landscape photography equivalents are the ones shot in Yosemite (or similar) during evidently pleasant weather, that have been heavily over-cooked in post, and then titled ‘_____, Clearing Winter Storm’.

Arrows and street signs. OK, so there is always going to be potential here. Never say never and all that, but I wish I could erase memory of every photo like the one below I have seen and wish I could un-see.

So what do you think about these photographs?

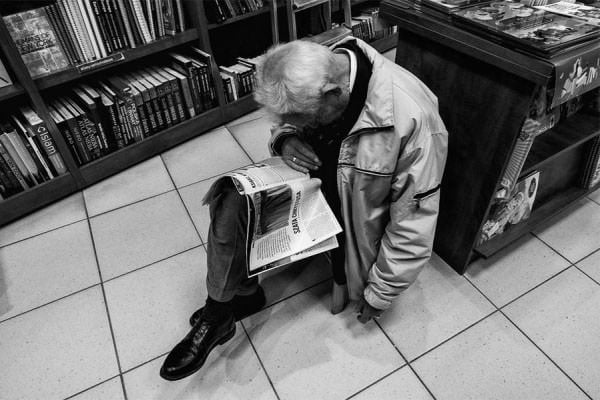

Note: These following street photos are being shared under fair use for commentary and critique. The names of the photographers have been omitted to not single any artist out in a negative way. Anyone who wishes to have their photo removed will have their request respected immediately.

What goes in comes out

Really engaging photographs are never the product of laziness, or formula, but this does not mean it should be hard work either. “Endeavor” is perhaps the best term. If we put in effort (and some thought) we can generally produce photographs worth more than a quick glance. That does not mean waiting for all of two minutes until a man of the right height walks past a poster depicting a large open mouth. Such photos are simply the free version of buying a ticket to Yosemite and placing your tripod in the exact spot ‘Clearing Winter Storm’ was taken 75 years earlier. It’s easy. It requires no real effort, thought or (most importantly) personal investment.

I am not suggesting a hipster coffee approach here. Riding to the Andes on a unicycle to collect the coffee does not make it taste any different. Working your ass off in photography without that effort actually affecting your photographs is no different. However, just engaging in the subject of photography helps. Learning a little more about yourself helps. Learning about the people and environment around you and your thoughts and reactions to it helps. The sad truth is that most of our effort in photography amounts to nothing. We’ve all worked hard and come back with a slew of entirely disappointing images, but this does not mean we stop trying.

Street photography is fantastic and compelling, but it is also incredibly difficult to do well. In part, this is because we have seen so much of it before. Brilliant, obsessive workaholics have been doing it for 70 years, but they aren’t us. They haven’t had our experiences. They haven’t seen everything through the same eyes. Their insights are not ours. Every single person wielding a camera has the potential to say something interesting, or see something engaging. Again, it comes down to relationships and, even on the street, our relationship with what is in front of the camera is key.

Once a photographer has learned a few ‘tricks’, they are presented with a choice: keep chasing gimmicks or formulas, or look deeper. It’s OK to be lost. It’s OK not to know what you’re doing. It’s OK to fail. It’s absolutely fine to feel insecure about your work. In fact, all of these things are very cool because they state very loudly that a person is trying, striving, exploring and searching in a very personal sense…. call it what you will.

It is this highly individual engagement that makes photography interesting. Street photographs needn’t take that away. It isn’t an altar that photographers must worship beneath and it isn’t a sport either. Some years ago I read a passage in a men’s magazine advising young men not to approach their sexual endeavors in the same way as they might improvements to their sporting performance. And here we are back to the supreme importance of relationships, expression and connection. Without these things, both just become repetitive, predictable acts that lose their luster.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

About the author: After studying Biological Sciences at Bristol University, Thomas served in the British Army before spending fifteen years living and photographing in conflict zones as a civilian. His work has won numerous international awards and has been exhibited in the UK, US, Europe. You can find more of his work and writing on his website and The Photo Fundamentalist. This article was also published here.