The most dangerous part of the car generally sits in the driver’s seat. And that’s doubly true if the car is a flying car.

The notion of such aerial vehicles has always fascinated, but the pesky need to pilot the things has generally grounded it — as if the engineering and legal challenges weren’t enough already. But autonomous driving technology may be the missing piece that leads us to the place where, yes, we won’t need roads.

A report in Bloomberg Businessweek reveals that Larry Page has been funding a pair of flying car companies for, I’m pretty sure, exactly the reasons you’d guess.

Zee.Aero has been around since 2010, quietly prototyping fliers at its headquarters deep, deep in the South Bay. Bloomberg reports that it has nearly 150 employees, and that Page has put more than $100 million into it.

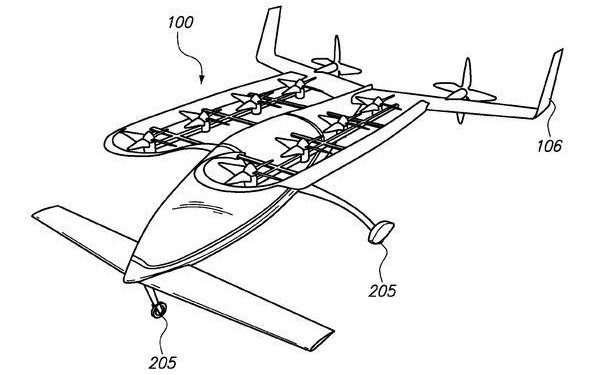

Patent drawing for a flying passenger vehicle that, believe it or not, they’ve actually built one of.

Kitty Hawk started up last year, with former Google self-driving car wizard Sebastian Thrun at its head. The implication in the report is that it’s the smaller, more agile team put together to nip at the heels of the other.

The specifics of their flying car projects, however, are of little interest. People have been trying to make flying cars for a long time, and so far the only design that really works is Terrafugia‘s, which is just about the ugliest, most prosaic “flying car” one can imagine. It’s really more of a rolling plane. (Not like I could make a better one, of course.)

The Terrafugia Transition. Not pictured: your childhood hopes and dreams.

On that note, we really should stop saying “flying car” altogether. Passenger drone, perhaps, or flier, or bandit or personal airborne transport. A name will appear sooner or later, but you’re not going to say, “Sure I’ll be there in 15 minutes. Just about to get into a flying car.”

Dozens of companies and designs have come up over the decades, and with ultralight composites and better battery tech we may actually be drawing near a basic functional design. But it has always seemed to be a hollow promise, because, really, how the hell did you expect to fly the things?

It was always the part we seemed to gloss over in our imaginations. We skipped over the preflight checks, restricted airspace, air traffic control, lessons in aerodynamics and, of course, the eight-figure price tag, visualizing only flying peacefully above the countryside and landing, somehow, at Uncle Kent’s farm.

The reality is that the necessity of having a trained and licensed pilot at the helm of this imaginary flying car is as great a challenge to the dream as the actual creation of the vehicle itself, or the 10,000 miles of red tape that will prevent its takeoff.

Fortunately, self-driving cars are here to change that.

Autonomy trifecta

When you think about it, autonomous vehicle tech and flying cars are like peanut butter and jelly. One is sort of incomplete without the other.

Self-driving vehicles seem practical but feel somehow lazy (after all, you can more or less do what they do), and the idea that humans could fly cars around without every one of them crashing and dying is optimistic to say the least. Self-driving cars need to fly in order to be more than ordinary, and flying cars need to be self-driving to be less than lethal.

This may seem rather obvious now, but until a few years ago autonomous cars were just as much a fantasy as flying ones. It speaks much of the work put in by the developers of self-driving vehicles that the concept has gone from science fiction to banal reality in the space of a decade. Once something is boring, it’s ready for the mainstream.

These children, one of whom is actually dressed as an Enderman from Minecraft, will grow up thinking self-driving cars are boring.

The biggest beneficiary of self-driving research has to be the burgeoning field of computer vision, once a niche for industrial robotics and academics, now a critical component in vehicle AI. Anyone in the field will tell you how much things have changed in the last few years. Multiple independent projects are building enormous libraries of visual data and techniques that will inform the collective unconscious, if you will, of future AIs.

The other missing piece is drones: The emergence of quadcopters with sophisticated stability and pathfinding software has accelerated the space in several ways. Not only are the basic routines for keeping a multi-rotor craft aloft and stable getting better and better, but we are also seeing critical safety features like safe emergency landings, protection from signal hijackers and awareness of other nearby drones for mutual avoidance purposes.

The future is autopilot

Add these up and a flying passenger vehicle that pilots itself from place to place seems a natural addition to the increasingly dense and varied connective tissue of a modern city.

Certainly no human — not even Elon Musk — could do what a flier would have to, tapping into the data streams of 10,000 other vehicles, sensors and libraries, crunching the metadata of a living city while maintaining flight stable enough that its passengers’ coffee doesn’t spill.

Even if there were such a human, there’s just no way the FAA will let people fly their own cars around the city. In a few decades it may seem absurd that we drove our own cars for a century, with the dead from traffic accidents totaling in the millions.

But transportation is in the process of changing from something you do to a service you access. And as part of that change, autonomous fliers (or whatever we’ll call them) actually just make sense — for rich people and emergencies at first (as with just about everything) and then, eventually, for everyone.

We have rapidly switched from thinking of Google’s little buggies less as a science project and more as a practical part of a near-future transportation infrastructure. Over the next decade, fliers too may suddenly reach that level of believability, where you stop dreaming about doing barrel rolls on the way to work and start worrying about how noisy they’ll be and how you can avoid having a landing pad on your block.

Featured Image: Bryce Durbin / TechCrunch