The world of online gaming is changing so quickly that players, developers, publishers and regulators are all scrambling to keep up with each other. Case in point: loot boxes, randomized in-game rewards that may or may not have monetary value or be purchasable with real money, are after years of deployment only now being scrutinized globally for being what amounts to thinly veiled gambling.

A suggestive new study from British researchers and a just-announced coalition of governments are the latest indicators that the loot box phenomenon and its derivatives likely won’t continue to be the wild west they’ve been for the last few years.

Many factors have led games to resemble services or channels more than pieces of entertainment with a start and end. And that in turn has changed how these games are monetized. As an alternative to a $60 up-front cost or a $10/month subscription, a game may be released for free but supported with in-game purchases of various kinds, including loot boxes.

Loot boxes usually contain a random reward, such as a new item for your in-game character. They can be earned by playing the game (usually a lot), but often can also be bought. Not only this, but the items have a sort of black market value and are traded among players and indeed gambled in a highly unregulated economy that reports put on the order of billions of dollars.

Although gaming companies compare it to collecting baseball cards or getting a toy in a box of cereal, the reality is plainly more complex than that, and the idea has led to extreme versions where players are constantly urged to buy in-game currencies and rewards. There’s no doubt that companies like EA and Tencent have made enormous amounts of money by luring players into purchases in “free to play” games.

The report, instigated earlier this year by an Australian parliamentary committee, was conducted by David Zendle and Paul Cairns, of York St. John University. The study is a limited one, they are quick to point out, but there is essentially nothing else on the topic and even the most basic research is warranted. “Such work is urgently needed,” they write in the introduction.

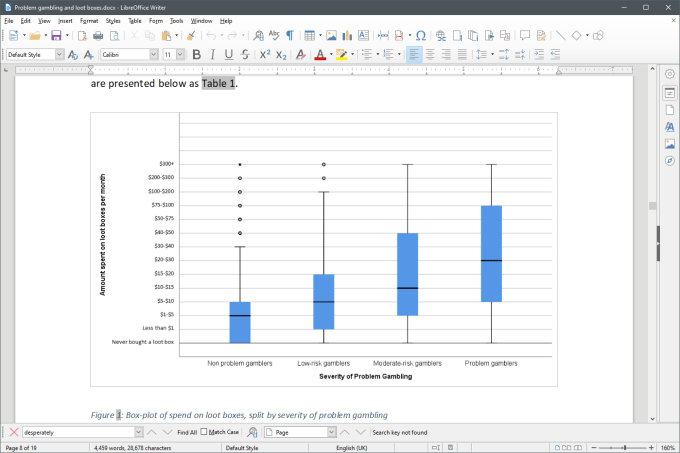

For their study, they surveyed thousands of gamers recruited from Reddit about their habits and spending. What they found was that gamers tending toward “problem gambling” habits (i.e. spending or behavior that negatively affects everyday life and relationships) spent considerably more on loot boxes than normal gamers — yet that wasn’t the case for general microtransactions like outright buying an in-game item or currency.

In the summary issued today to Australia’s Committee on Environment and Communications, they write:

In the summary issued today to Australia’s Committee on Environment and Communications, they write:

We found that the more severe an individual’s problem gambling, the more they spent on loot boxes. The relationship we observed was neither trivial, nor unimportant. Indeed, the amount that gamers spent on loot boxes was a better predictor of their problem gambling than high-profile factors in the literature such as depression and drug abuse.

As anyone with a critical eye for research will have noted by now, and as the researchers point out, this correlation could go either way. In either case, however, it doesn’t look good for the practice:

It may be the case that loot boxes in video games act as a gateway to other forms of gambling, leading to increases in problem gambling amongst gamers who buy loot boxes.

However, it is important to note that an alternative explanation for these results may also be true. The key similarities between loot boxes and gambling may lead to gamers who are already problem gamblers spending large amounts of money on loot boxes, just as they would spend similarly large amounts on other kinds of gambling. In this case, loot boxes would not be providing a breeding ground for the development of problem gambling so much as they would be allowing games companies to exploit addictive disorders amongst their customers for profit.

The researchers conclude that either way, the practice merits more research and possibly regulation. It’s not the same as ordinary gambling, they say, but it’s similar enough that it warrants controls like those exerted on, say, online poker, to prevent harm and abuse.

Governments around the world are split on how to characterize loot boxes, with Belgium taking a severe enough stance that Blizzard was forced to stop offering loot boxes for real money in its popular team shooter Overwatch. But French and German authorities disagreed and have to a certain extent accepted the argument that the practice is more like opening a Kinder Egg or collectible card game pack.

But this uncertainty is itself galvanizing, apparently. A coalition of 15 gambling authorities, including the U.K., France, Portugal, Norway and the U.S. (via tech-savvy Washington State’s gambling commission), issued a shared declaration that they intend to look into these shenanigans and they expect the companies involved to play ball:

We are increasingly concerned with the risks being posed by the blurring of lines between gambling and other forms of digital entertainment such as video gaming. Concerns in this area have manifested themselves in controversies relating to skin betting, loot boxes, social casino gaming and the use of gambling themed content within video games available to children.

We commit ourselves today to working together to thoroughly analyse the characteristics of video games and social gaming. This common action will enable an informed dialogue with the video games and social gaming industries to ensure the appropriate and efficient implementation of our national laws and regulations.

We anticipate that it will be in the interest of these companies whose platforms or games are prompting concern, to engage with [gambling] regulatory authorities to develop possible solutions.

Tying it to kids is a good way to stay on the moral high ground, but there aren’t a lot of problem gamblers in the under-18 bracket. The truth is that while kids are certainly at risk, the problems associated with loot boxes threaten all gamers and indeed the basic economic grounding of gaming itself.

A letter of intent is a start and may cause a change in the ecosystem as developers and publishers aim to make their loot box systems less exploitative (as some have already done) and (what is more likely) engage in a charm offensive to normalize the practice and distance it from more traditional gambling. At the very least it is good to know that there is action afoot in an area that has frustrated and certainly lightened the wallets of millions of gamers.