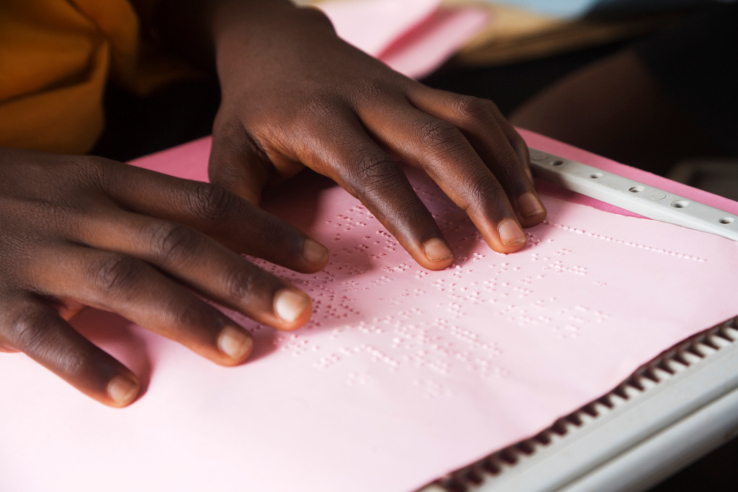

It’s difficult enough already for the visually impaired to read the books and publications sighted people take for granted, but it’s downright impossible when the content isn’t even available in accessible formats. Fortunately, a global agreement aimed at alleviating the problem passed a major milestone today and may take effect before the end of the year.

The Marrakesh Treaty is a proposed set of rules designed by the World Intellectual Property Organization, a division of the U.N. that helps alleviate cross-border IP issues. Marrakesh would create exceptions to copyright laws, allowing reproduction of works in accessible formats like Braille, audio or e-book, and easing restrictions on passing those works between countries.

The range of disabilities, needs and means of access are very wide: A person who is paralyzed or lacks hands has very different requirements from someone who is blind, or someone suffering from dyslexia.

Marrakesh isn’t some hot new idea; the treaty has been under construction and negotiation for a decade — which isn’t surprising, since big international agreements aren’t simple by any means. Of course, it doesn’t help that major copyright holders like the MPAA have opposed it — limiting its scope from affecting things like subtitles.

Ironically, the U.S. is one of the few lucky countries that already offers the copyright limitations the treaty seeks to internationalize — and with major organizations willing to do so. In fact, just yesterday, HathiTrust and the National Federation of the Blind announced the release of more than 14 million books into an online repository for the blind and print-disabled.

Opposition notwithstanding, things appear to be coming to a conclusion in a flurry of activity: Ecuador and Guatemala acceded to the treaty yesterday, and Canada did so today, becoming the critical 20th country to accede to Marrakesh, allowing it to be “entered into force.” India, it is worth mentioning, was the first to ratify, two years ago.

Representatives from Canada (left), Guatemala (center) and Ecuador present documents to WIPO’s Francis Gurry.

“The Marrakesh Treaty will, when widely adopted throughout the world, create the framework for persons who are blind and visually impaired to enjoy access to literacy in a much more equal and inclusive way,” said WIPO Director General Francis Gurry in a press release.

Entry into force means WIPO can start nagging signatory countries into fulfilling their promises and making the treaty’s provisions into actual law. This should occur on September 30, though don’t expect a flood of Braille translations on October 1 — laws still need to be written and organizations chosen or formed to oversee the process of translation and distribution.

Still, however slow it’s been, it’s better than having nothing at all. Within a few years it should be considerably easier for someone who is unable to read a traditional print book to find an alternative.

[hat tip: EFF]

Featured Image: Liba Taylor / Getty Images