Microsoft tried to sell its facial recognition technology to the Drug Enforcement Administration as far back as 2017, according to newly released emails.

The American Civil Liberties Union obtained the emails through a public records lawsuit it filed in October, challenging the secrecy surrounding the DEA’s facial recognition program. The ACLU shared the emails with TechCrunch.

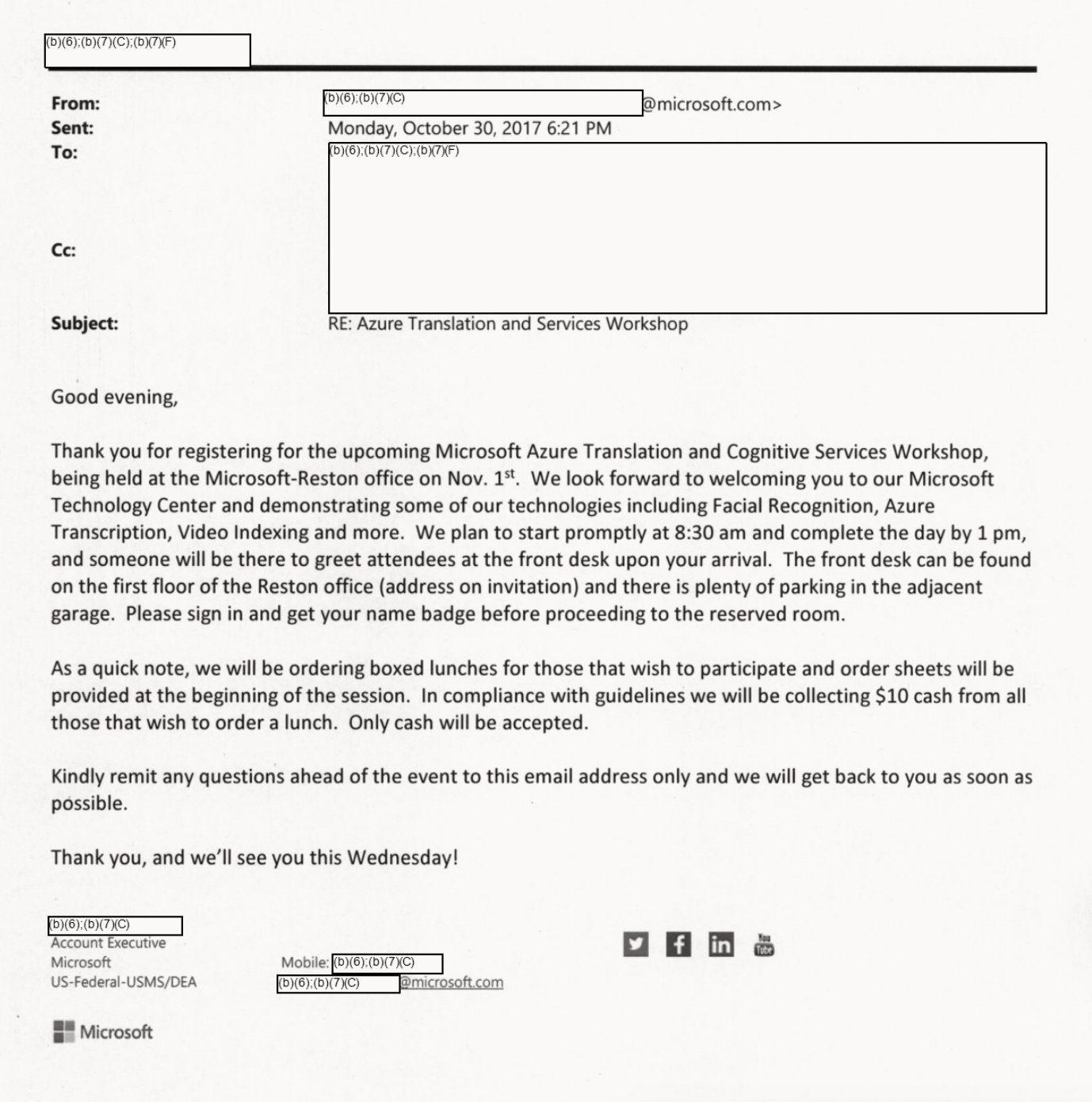

The emails, dated between September 2017 and December 2018, show that Microsoft privately hosted DEA agents at its Reston, Virginia office to demonstrate its facial recognition system, and that the DEA later piloted the technology.

It was during this time that Microsoft’s president Brad Smith was publicly calling for government regulations covering the use of facial recognition.

But the emails also show that the DEA expressed concern with purchasing the technology, fearing criticism from the FBI’s use of facial recognition at the time that caught the attention of government watchdogs.

Critics have long said this face-matching technology violates Americans’ right to privacy, and that the technology disproportionately shows bias against people of color. But despite the rise of facial recognition by police and in public spaces, Congress has struggled to keep pace and introduce legislation that would oversee the as-of-yet unregulated space.

But things changed in the wake of the nationwide and global protests after the death of George Floyd, which prompted a renewed focus about law enforcement and racial injustice.

An email from a Microsoft account executive inviting DEA agents to its Reston, Virginia office to demo its facial recognition technology. (Source: ACLU/supplied)

Microsoft was the third company last week to say it will no longer sell its facial recognition technology to police until more federal regulation is put into place, following in the footsteps of Amazon, which put a one-year moratorium on selling its technology to police. IBM went further, saying it will wind down its facial recognition business entirely.

But Microsoft, like Amazon, did not say if it would no longer sell to federal departments and agencies like the DEA.

“It is bad enough that Microsoft tried to sell a dangerous technology to a law enforcement agency tasked with spearheading the racist drug war, but it gets worse,” said Nathan Freed Wessler, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU. “Even after belatedly promising not to sell face surveillance tech to police last week, Microsoft has refused to say whether it would sell the technology to federal agencies like the DEA,” said Wessler.

“This is troubling given the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s record, but it’s even more disturbing now that Attorney General Bill Barr has reportedly expanded this very agency’s surveillance authorities, which could be abused to spy on people protesting police brutality,” he said.

Lawmakers have since called for a halt to the DEA’s covert surveillance of protesters, powers that were granted by the Justice Department earlier in June as protests spread across the U.S. and around the world.

When reached, DEA spokesperson Michael Miller declined to answer our questions. A spokesperson for Microsoft did not respond to a request for comment.