The broadband divide in the U.S. is real, but if you want to know how real, don’t ask the FCC. Its yearly broadband deployment report, already under fire for serious data problems, has now been further questioned by Microsoft, which says its own data contradicts coverage data provided by internet providers. Despite $22 billion in government spending, the company says, “adoption has barely budged.”

In a blog post, Microsoft explained that it was concerned with apparent inaccuracies in reports purporting to document broadband availability throughout the country. Leveraging data sourced from its various online services, it came to vastly different conclusions than the FCC.

“We have 200 services that we operate as a company,” said Microsoft President Brad Smith in a recent talk. “We can see download speeds across the country, and in every county, and we’ve assembled our own map with our own estimates.”

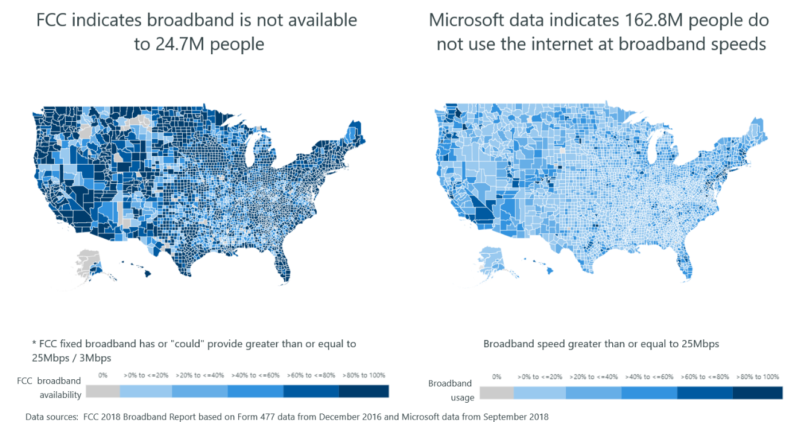

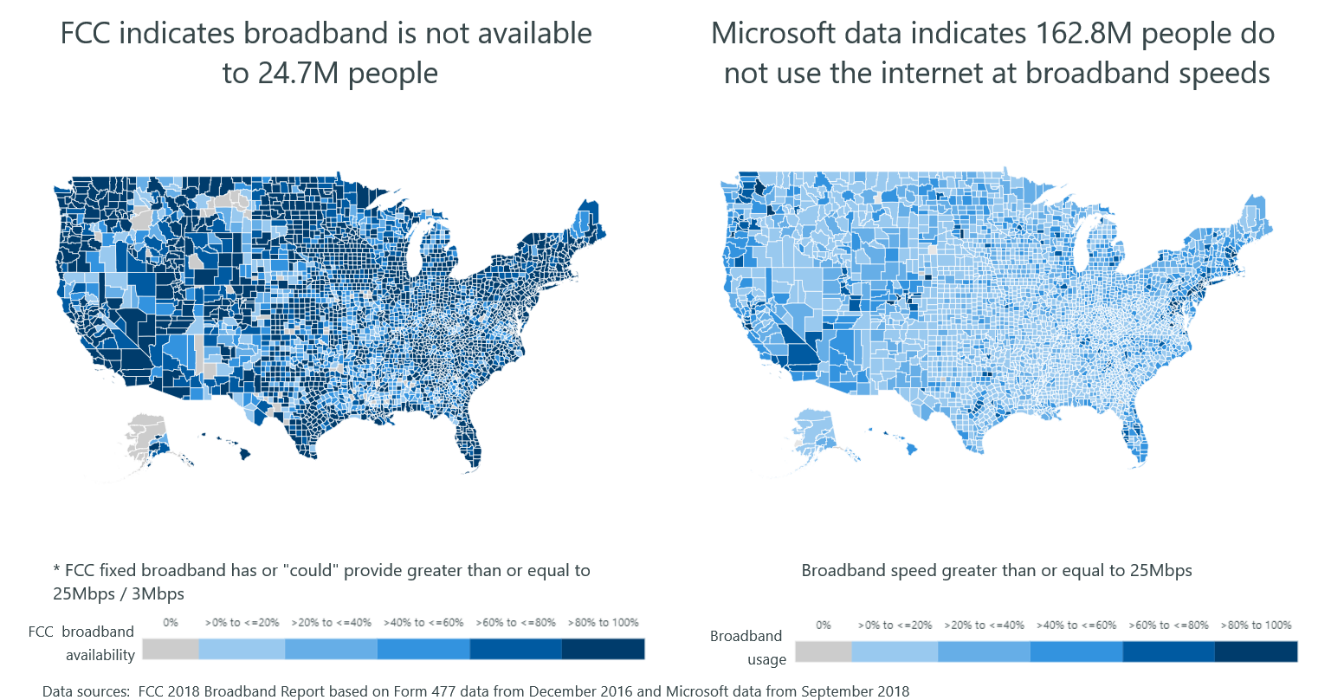

For instance, the FCC report suggests that broadband, as it is currently defined, is not currently available to around 25 million people. Sounds reasonable. But Microsoft’s data says that some 163 million people “do not use the internet at broadband speeds.”

Those aren’t the same thing, obviously, but you’d think if a person had broadband available they would use it at least now and then, right?

To look further into the problem, Microsoft checked out a few locales:

In our home state of Washington, the FCC data indicates that 100 percent of Ferry County residents have access to broadband. When we spoke to local officials, they indicated that very few residents in this rural county had access and those that did were using broadband in business. Our data bears this out, showing that only 2 percent of Ferry County is using broadband.

So the entire county has broadband, but next to no one uses it? Seems odd. The pattern repeats elsewhere as well, rural and urban, with similar deltas between reported broadband availability and observed broadband activity.

“These significant discrepancies across nearly all counties in all 50 states indicates there is a problem with the accuracy of the access data reported by the FCC,” concludes Microsoft’s chief data analytics officer, John Kahan.

Part of the issue is that internet providers essentially just report their own coverage via a form, and the FCC reports it more or less as fact. That’s a problem not just when a mistake on a form adds tens of millions of subscribers that don’t actually exist, but when large ISPs overstate their coverage so they don’t have to pay to fill in the gaps.

Part of the issue is that internet providers essentially just report their own coverage via a form, and the FCC reports it more or less as fact. That’s a problem not just when a mistake on a form adds tens of millions of subscribers that don’t actually exist, but when large ISPs overstate their coverage so they don’t have to pay to fill in the gaps.

Microsoft’s suggestions, which it has made to Members of Congress and the FCC (though it won’t, as I originally wrote here, testify in the Senate on Wednesday) would make it far more difficult to fib on the Form 477, which as written seems to provide enormous leeway for a company to imply coverage that isn’t actually there.

The problems described here are not new or obscure, and even FCC commissioners have taken issue with the way this data is collected. Hopefully given the continued and growing outcry concerning this misleading report we will soon know better who in our country has, or needs, help getting online. That the FCC wants to help I don’t doubt, but in order to do so they need better data.