A European satellite that measures the Earth’s winds using lasers had a close encounter with one of SpaceX’s Starlink constellation yesterday in a situation that illustrates the growing inadequacy of existing systems for global coordination of orbital issues. It’s getting crowded up there, and email and phone calls between HQs soon won’t cut it.

The near miss was announced yesterday on Twitter by the European Space Administration’s Operations team. It explained, perhaps a might sensationally, that “for the first time ever, ESA has performed a ‘collision avoidance manoeuvre’ to protect one of its satellites from colliding with a ‘mega constellation’ .”

To be clear, and as ESA explained, these maneuvers are actually very common — but they’re almost always to avoid debris and dead satellites, not active ones. These days when you launch a satellite, you’re generally very careful to put it in an orbit that has been carefully calculated to not intersect with that of any other satellite. Pretty straightforward, right?

But things happen; for instance a thruster misfires or another maneuver goes wrong, and suddenly a satellite that was going to pass within a safe distance of another one is actually going to get much, much closer. That’s what seems to have happened here: the Starlink satellite, one of 60 launched earlier this year, somehow found itself on a potential collision course.

SpaceX and ESA exchanged emails on August 28, when the chance of the two craft colliding was around 1 in 50,000; they determined no action was necessary. But a subsequent update from the U.S. Air Force’s tracking infrastructure changed that estimate to about 1 in 600. That’s well below the 1 in 10,000 chance standard for taking measures. (This isn’t just guesswork but allowing for jitter in measurements and other noise that enter tracking of fast-moving orbital objects.)

Here’s where the hiccup happened. With the new and scary probability of a collision, either ESA or SpaceX had to change orbit — again, something that happens a lot, but in this case needs to be coordinated clearly with the other. What if they both adjusted their orbit the same way and increased the chance of disaster?

Unfortunately, SpaceX was not aware of the new probability estimate from the Air Force, and as such persevered in its decision not to adjust its satellite’s trajectory. As a result, the ESA had to make its own maneuver — not fun when the craft in question is performing extremely sensitive measurements using a high-powered lidar system.

Why would SpaceX not want to do anything? Apparently they weren’t in possession of the new, higher estimate.

“A bug in our on-call paging system prevented the Starlink operator from seeing the follow on correspondence on this probability increase,” SpaceX said in a statement. “Had the Starlink operator seen the correspondence, we would have coordinated with ESA to determine best approach with their continuing with their maneuver or our performing a maneuver.”

Ultimately there was no collision and both satellites are happily orbiting the Earth, though Aeolus does have a touch less fuel than before. The problem is not that a satellite had to swerve a bit, because that happens all the time. The problem is that it was an encounter with an active satellite and communications between the two operators was inadequate.

“Nobody did anything wrong. Space is there for everybody to use,” ESA’s Holger Krag told Forbes. “Basically on every orbit you can encounter other objects. Space is not organized. And so we believe we need technology to manage this traffic.”

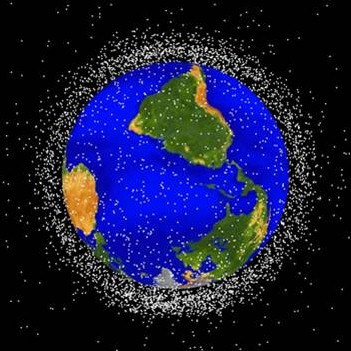

Visualization of space debris around Earth.

With plans by SpaceX, Amazon, OneWeb and others to launch constellations of hundreds or thousands of satellites over the years, the possibility of another such encounter is very likely. And a system that worked when there were vanishingly few encounters between active satellites likely won’t work when those encounters are a daily or hourly occurrence.

“This example shows that in the absence of traffic rules and communication protocols, collision avoidance depends entirely on the pragmatism of the operators involved. Today, this negotiation is done through exchanging emails – an archaic process that is no longer viable as increasing numbers of satellites in space mean more space traffic,” said Krag in an ESA news post.

“No one was at fault here, but this example does show the urgent need for proper space traffic management, with clear communication protocols and more automation. This is how air traffic control has worked for many decades, and now space operators need to get together to define automated maneuver coordination,” he continued.

Naturally AI is being brought into the discussion, but also other common-sense rules and improvements to an aging system that is no longer able to be ignored. It plans to make these proposals more solid later this year and hopefully put them into action.