As part of its effort to steel its platform against threats to the 2020 election, Facebook will try surfacing accurate voting info in a new place — on politicians’ own posts.

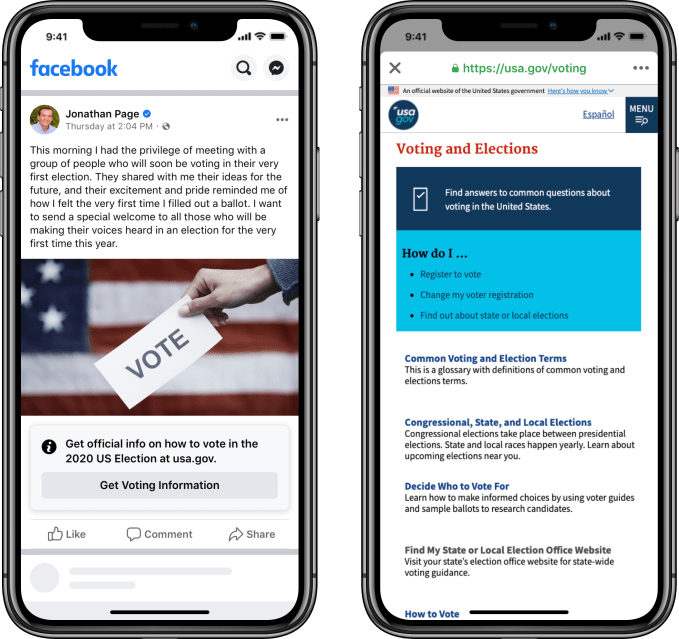

Starting today, Facebook posts by federal elected officials and candidates — including presidential candidates — will be accompanied by an info label prompting anyone who sees the post to click through for official information on how to vote. The label will link out to usa.gov/voting. For posts that address vote-by-mail specifically, the link will point to a section of the same website with state-by-state instructions about how to register to vote through the mail.

Image via Facebook

Facebook plans to expand the voting info label to apply to all posts about voting in the U.S., not just those from federal-level political figures. That plan remains on track to launch later this summer with Facebook’s Voter Information Center, its previously announced info hub for official, verified information related to the 2020 election. The voter info center, like the coronavirus info center Facebook launched in March, will be placed prominently in order to funnel users toward useful resources.

The company did not mention any specific reason for the decision to prioritize elected officials before other users, but in May Facebook faced criticism for its decision to allow false claims by President Trump about vote-by-mail systems and the 2020 election to remain on the platform untouched. At the time, Twitter added its own voting info label to the same posts, which also appeared as tweets from the president’s account.

In a June post, Mark Zuckerberg discussed voter suppression concerns, saying that Facebook would be “tightening” its policies around content that misleads voters “to reflect the realities of the 2020 elections.” Facebook will also focus on removing false statements about polling places in the 72 hour lead-up to the election. Zuckerberg said that posts with misleading information that could intimidate voters would be banned, using the example of a post falsely claiming ICE officials are checking for documentation at a given polling location.

Zuckerberg made no specific mention of President Trump’s own false claims that expanded mail-in voting in light of the coronavirus crisis would “substantially fraudulent” and result in a “rigged election.” Zuckerberg did say that Facebook would begin labeling some “newsworthy” posts from political figures, leaving the content online but adding a label noting that it violates the platform’s rules.

While false claims from political figures are a cause for concern, they don’t account for the bulk of voting misinformation on the platform. A new report from ProPublica found that many of Facebook’s most well-performing posts about voting contained misinformation. “Of the top 50 posts, ranked by total interactions, that mentioned voting by mail since April 1, 22 contained false or substantially misleading claims about voting, particularly about mail-in ballots,” ProPublica writes in the report, noting that many of the posts appear to break Facebook’s own rules about voting misinformation but remain up with no labels or other contextualization.

While its past enforcement decisions remain controversial and often puzzling, Facebook does appear to be rethinking those choices and gearing up its efforts in light of the coming U.S. election. For Facebook, which goes to sometimes self-defeating lengths to project an aura of political neutrality, that’s less about expanded fact-checking and more about making correct, verified voting information at hand and readily available to users.

In early July, Facebook announced a voter drive that aims to register 4 million new U.S. voters. As part of that effort, Facebook pushed a pop-up info box to app users in the U.S. reminding them to register to vote, check their registration status with links to official state voter registration sites. Those notifications will soon appear in Instagram and Messenger as part of the same voter mobilization push.

Facebook is also apparently mulling the idea of banning all political advertising in the lead-up to November, a decision that would likely alleviate at least one of the company’s headaches at the cost of leaving both political parties, which rely on Facebook ads to reach voters, frustrated.