You can add the cult classic Super Smash Bros Melee to the list of games soon to be dominated by AIs. Research at MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory has produced a computer player superior to the drones you can already fight in the game. It’s good enough that it held its own against globally-ranked players.

In case you’re not familiar with Smash, it’s a fighting game series from Nintendo that pits characters from the company’s various franchises against each other. Its cutesy appearance belies its strategic depth: “The SSBM environment has complex dynamics and partial observability, making it challenging for human and machine alike. The multiplayer aspect poses an additional challenge,” reads the paper’s abstract.

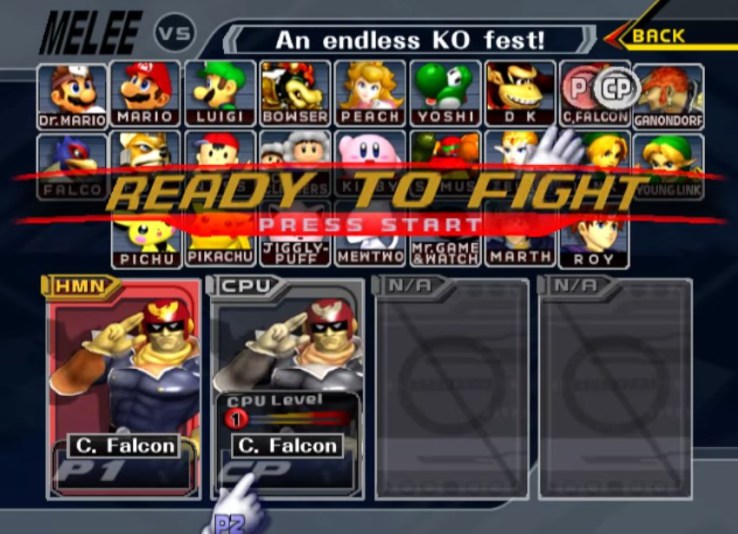

The team, led by Vlad Firoiu, trained a neural network model to play the game by feeding it the coordinates of all the gameplay items — players, ledges, and so on — and incentivizing play that resulted in the computer’s victory. It doesn’t watch the screen and learn from that, as some systems do, but is more like an in-game computer player that’s learned everything from scratch.

Its playing style, as so often seems to be the case with these models, is a mixed bag of traditional and odd:

“It uses a combination of human techniques and some odd ones too – both of which benefit from faster-than-human reflexes,” wrote Firoiu in an email to TechCrunch. “It is sometimes very conservative, being unwilling to attack until it sees there’s a opening. Other times it goes for risky off-stage acrobatics that it turns into quick kills.”

That’s the system playing against several players ranked in the top 100 globally, against which it won more than it lost. Unfortunately it’s no good with projectiles (hence playing Caption Falcon), and it has a secret weakness:

“If the opponent crouches in the corner for a long period of time, it freaks out and eventually suicides,” Firiou wrote. (“This should be a warning against releasing agents trained in simulation into the real world,” he added)

It’s not going to win the Nobel Prize, but as with Go, Doom, and others, this type of research is a good way to see how existing learning models and techniques stack up in a new environment.

You can read the details in the paper at Arxiv; it’s been submitted for consideration at the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Melbourne, so best of luck to Firoiu et al.