Esports is becoming a true spectator sport, but will the average Joe one day care about competitive League of Legends or Overwatch or Counter-Strike the way they care about watching football on Sundays?

A number of factors are at play for esports to garner the same level of popularity as mainstream sports like football, baseball, basketball and fútbol everywhere but the U.S., some of which are within the control of the gaming industry and some that are not.

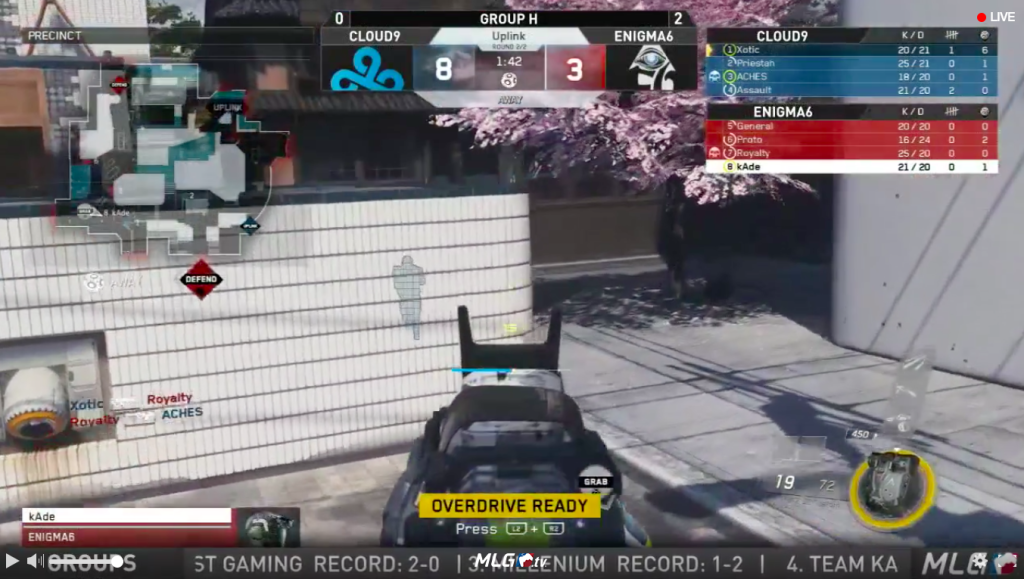

This week, CWL Champs is underway. It’s the grand finale to a year-long season of Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare, and the first-place team will take home $600,000, the largest chunk of the $1.5 million prize pool for the tournament. Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare is the No. 4 competitive video game in terms of earnings, according to e-Sports Earnings. And it’s through the lens of this franchise, its competitive history and this particular tournament that we can look at the various ingredients necessary to take esports into the mainstream.

Infrastructure

Where would the NFL be without stadiums and broadcast television? Esports as an entity is a toddler at this point, but there’s visible growth happening when you look at the way these leagues are maturing. Though competitive Call of Duty has a rich history, it wasn’t until January 2016 that Activision introduced the Call of Duty World League (CWL).

The CWL brings with it a direct line to the game-makers themselves, which makes the prize pool bigger and the viewing experience better. Casters, the folks who drive the viewing experience for the audience and commentate over the action, are now able to actually offer a high level of production value to the experience.

For example, Activision and Treyarch made it possible for casters to change the colors of the teams to fit their real-world team colors for the Black Ops 3 seasons. The caster also offers the ability to silhouette players in their team color whether or not they’re in direct view on the screen.

“The line of scrimmage in the NFL is a big inspiration for player silhouettes,” said Kevin Flynn, director of product marketing for the CWL. “We try to be hyper aware of innovations that impact the viewing experience of spectators.”

For reference, the talent at the professional Call of Duty level is so high that most players are usually behind full-body cover at any point in the game. To an amateur, without player silhouettes, we’d have a difficult time seeing any of the players on the map at all.

This seems like pretty obvious stuff, but these refinements wouldn’t be possible if the publisher of the game wasn’t somewhat invested in the competitive league play and viewing experience.

Sometimes that investment comes in the form of an ever-refining CoD-caster, and sometimes it comes in the form of actual investment. Activision acquired MLG.tv in January 2016, just before the launch of the CoD World League, in a deal valued at $46 million. Plus, Activision has implemented an in-game streamer so that folks playing IW or Black Ops 3 on a PlayStation 4 can watch directly from their console. And that doesn’t include the live streaming on YouTube, Twitch, Facebook and even on broadcast TV in Europe.

Now, this is hardly ESPN, but it’s a start to uniting the game-makers and the viewers under the same roof. And while most viewers of a tournament like CWL Champs are amateur CoD players or industry folks, it’s not difficult for a non-gamer to make the leap into watching a game like this.

Last weekend was the Stage 2 Playoffs, which determined the seeds for this weekend’s Champs tournament. I happened to be tuned in when a handful of friends came over, and threw it up on the big screen when they arrived. Three of my five guests never played Call of Duty, and certainly never watched esports. And yet, after peppering in a few questions to understand the basics, they seemed perfectly content and maybe even excited to watch the action go down.

Narrative

Part of that is due to the casters, who work hard to explain the rules of the game, the strategies and the context of those strategies in laymen’s terms.

But beyond explaining the difference between gamemodes like Hardpoint, Uplink and Search & Destroy, these casters also do an incredible job of setting up the storylines of the teams and the players. This is yet another area where the CWL is taking cues from Big Sports.

“The casters do a great job of demystifying things, breaking down and celebrating big moments, just as traditional sports have done so well,” said Flynn. “We’re also trying to emphasize the star power of these guys and celebrate rivalries, as the NBA has done so fabulously with players like LeBron versus Stef Curry, and Kyrie Irving versus Kevin Durant.”

Unfortunately, Call of Duty happens in a digital world with virtual characters, and the viewer doesn’t necessarily get to know Clayster or Scump or Gunless as anything more than a gamertag on a screen. The CWL is working to give more insight to player profiles, and the players are putting themselves out there as real people with real lives.

For example, only a few weeks ago one of the greatest AR players in the game, James “Clayster” Eubanks, was traded from his long-time home at Faze Clan (a dominant force in competitive Call of Duty) to the new, rising team on the scene, eUnited. He was traded for the game’s newest superstar, Pierce “Gunless” Hillman.

And Clayster explained the whole thing to fans, in his own words, via YouTube.

It’s the equivalent of trading Dak Prescott for Aaron Rodgers, who fittingly is the mainstream athlete that Clayster most likens himself to.

“I’m a big Aaron Rodgers fanboy,” said Clayster. “I love the way he goes about things, the logical decisions he makes, always calm and cool. He shows hype when he does something crazy, but he’s always grounded in logic.”

So imagine the drama surrounding the Stage 2 Playoffs when eUnited outplaced Faze and Clayster went on to play in the finals of the tournament.

And then there’s the story of Optic Gaming, undoubtedly the most dominant team in Call of Duty for a few years running. Two of the veterans on the roster, Damon “Karma” Barlow and Ian “Crimsix” Porter, have won championship rings on other teams and have quite the resumes. But Seth “Scump” Abner (considered the best player in Call of Duty history) and Matthew “Formal” Piper (a legendary AR player who moved from competitive Halo a few years ago) have yet to get their rings.

“I think the worst thing to do is to put pressure on myself and the team,” said Scump. “It’s just another tournament, and we’re going to work map by map and go through it together. I can’t think about it.”

For some perspective, Optic Gaming is currently playing their first match of the day, and viewership on the MLG.tv stream alone is hanging around 50,000 viewers.

The last two years in a row, Optic Gaming has choked at Champs, despite the way they’ve dominated tournaments and league play. Will they finally clutch up this year? Will Scump and Formal get their rings?

Time

The NFL is nearly 100 years old, and esports is a baby by comparison. But the model of esports is around amateur players becoming viewers, and the ESA says that more than 150 million people play video games regularly in the United States alone.

That audience shouldn’t be difficult to convert, and each of those players-turned-viewers inevitably becomes some sort of evangelist for players of other games, or non-players. We watch action movies all the time, and we love rivalries and underdog stories. Esports brings those two things together in a way that is instantly gripping, even for this nearly 30-year-old female tech reporter.

Plus, the sheer amount of cash being pushed around in this industry is staggering. Forget the $4 million prize pool across the whole season of Infinite Warfare. These players have deals with brands like Lootcrate, Brisk Mate, Scuf, Turtle Beach, Astro Gaming and more. In fact, Optic Gaming just got an endorsement deal with Chipotle.

“I used to play for $2,500 for first place in tournaments and now I’m playing for $150,000 today,” said Scump. “And when the bigger matches of the tournament get going later today, this place is going to be insane.”

My generation dreamt of being a pop singer or a quarterback, making riches and bathing in fame. Today’s young people dream of playing video games to make their millions. Just this year, there are 20,000 players who are trying to be CoD pros by participating in the pro point program, up nearly 400 percent from last year.

These players are becoming role models, breaking stereotypes of the way that most people think of gamers.

“There’s a level of accountability you have to hold yourself to,” said Clayster. “The players and organizations have taken steps toward breaking the stereotype of the basement dweller. A lot of parents don’t understand it, but there are tons of fans watching me and looking up to me that I’ve met personally and I try to explain to them and their parents what a big deal it is. That we’re playing at Amway Center for $1.5 million.”

Just like my dad grew up watching football with his dad, and I grew up watching football with my dad, there is a generation of gamers out there who will raise their children watching esports. And I’ll probably be one of them.