If you’ve ever played Candy Crush on your smartphone during a morning commute, you’ll understand why some have compared it to an addictive drug. In fact, it’s an analogy that might be more true than most people realize. Beneath the surface of cheerful characters and colorful graphics is a booming empire worth billions in annual revenue — built to sell you your next fix of progress for the low price of an in-game purchase.

Taken in aggregate, mobile games now collectively represent a staggering 85 percent of all app revenues in any form — largely from the sale of such virtual goods. However, even this multi-billion-dollar market is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the possibilities for virtual goods sales in the coming waves of online media.

Virtual goods in virtual reality

One of the most striking elements of Ernest Cline’s recent hit novel Ready Player One was the vision of a fully immersive world built in virtual reality. Characterized by a limitless set of new products and experiences, this world inevitably became the focal point for both the personal and professional lives of millions of users. The result was a massive virtual economy catering to a growing population of digital denizens.

In fact, this futuristic scenario is not without precedent. Launched back in the early 2000s, the game Second Life was one of the first to approach this vision — reaching more than 1 million active monthly users and $3 billion in virtual goods transactions over the course of its lifetime.

The real question is, if users were willing to spend this much to experience virtual goods in a two-dimensional world, how much more might they spend to experience them in true VR? This would mean the difference between seeing fashionable clothes on your desktop avatar and feeling like you’re wearing them firsthand.

Virtual goods will both enable new experiences and redefine traditional ones.

Because virtual goods feel more real in virtual reality, they benefit from a higher perceived value. This is not only great news for consumers, who get to “experience” a more valuable set of new digital products and services, but also for developers, who benefit from nearly nonexistent marginal costs of production.

Augmented reality also presents its own set of opportunities. As display technologies advance to the point where virtual goods start to feel more tangible, we’ll not only see an increase in their value, but also their utility. Why buy a real 120” plasma screen when you can have a virtual one generated by your upgraded eyewear for much less? Especially when that virtual screen eliminates the need for installation and even follows you around the house so you don’t miss a minute of your favorite shows.

This persistent use case represents an important tipping point, where virtual goods could start cannibalizing the market for physical ones.

Online gambling and e-sports

Since the acquisition of Twitch by Amazon for nearly $1 billion in late 2014, the broader public has been paying far more attention to the growing popularity of e-sports. Between advertising, sponsorships, media rights, merchandise and ticket sales, this market is expected to generate $463 million in revenue in 2016 alone.

Beyond the obvious implications for virtual goods in gaming (i.e. players buying gear to improve their performance) is a secondary gray market that may be far larger — online gambling.

Thus far, the most advanced of these markets has sprung up around the game Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO for short). The reason is that the game’s developer, Valve, introduced decorative virtual weapons known as “skins,” which players can acquire in the game and sell for real money on third-party platforms (outside of the gaming environment). By 2015, this dynamic had given rise to an active gambling market comprising more than 3 million people wagering $2.3 billion worth of skins.

Following the trend of traditional sports, it was never really a question of whether e-sports gambling would emerge, but rather how it would emerge. Amazingly, by allowing virtual goods to migrate beyond the confines of its game, Valve created a currency that powered a tangential but distinct market. While Valve was eventually forced to curtail the practice because of regulatory pressure, latent consumer demand will almost certainly find a way to drive it back into the mainstream. After all, a $2 billion market doesn’t just disappear overnight.

Turning upgrades into investments

At first blush, Valve’s decision to allow virtual goods to leave their gaming platform may have seemed like a risky one. Rather than just pouring money into a single isolated game, players now had the ability to cash out and migrate their interests elsewhere. In theory, this could have made it much easier for players to quit the game. In practice, it significantly drove up the value of players’ investments.

The term “investments” is used very literally in this case, because the existence of an external market transmuted in-game purchases from simple upgrades into assets.

In fact, Valve is perfectly positioned to reap the benefits of a more open market for virtual goods. As the developer of Steam, one of the most popular PC gaming platforms, Valve’s performance isn’t just tied to a single game, but a broader connected ecosystem. Allowing players to migrate from one game to another represents a significant long-term value.

While virtual goods may never reach the status of more traditional asset classes like stocks or bonds, their growing value, appeal and transferability will unlock new opportunities for investors and developers alike. One thing is for certain — the days when “a sword was just a sword” may soon be behind us.

Building the guide rails

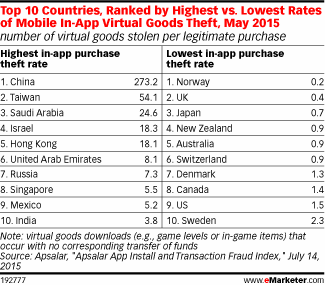

In a world where virtual goods play a more critical role in defining digital experiences, entrepreneurs will find a mix of new challenges and opportunities. For example, we’re already starting to see the emergence of rampant fraud in virtual goods transactions. In the first half of 2015, the global in-app purchase fraud rate — the number of virtual goods downloads that take place without revenue changing hands — was 7.49. When broken down by country, the U.S. came in at a moderate 1.5, while China reported an astronomical 273.2!

On the one hand, these fraud statistics reinforce the excitement and demand surrounding virtual goods, but on the other, they threaten to undermine the incentive for their creation. To address this risk, we will need to develop a new set of resources and tools to support the growing industry. Among the most pressing needs are: (1) creation tools for generating and distributing 3D content; (2) management tools for tracking and monetizing 3D content across platforms; (3) transactional tools for facilitating sales and exchanges between consumers; and (4) educational tools for the syndication of stats and important industry news.

On the one hand, these fraud statistics reinforce the excitement and demand surrounding virtual goods, but on the other, they threaten to undermine the incentive for their creation. To address this risk, we will need to develop a new set of resources and tools to support the growing industry. Among the most pressing needs are: (1) creation tools for generating and distributing 3D content; (2) management tools for tracking and monetizing 3D content across platforms; (3) transactional tools for facilitating sales and exchanges between consumers; and (4) educational tools for the syndication of stats and important industry news.

A look ahead

As we look ahead at the next evolution of our digital ecosystem, it seems certain that virtual goods will have a much larger role to play. From allowing us to vanquish a new breed of digital monsters to defining a modern asset class, virtual goods will both enable new experiences and redefine traditional ones. Along the way, this new gold rush will create plenty of opportunities for the enterprising prospector and shovel-seller alike.

Featured Image: Bryce Durbin/TechCrunch