What does consent as a valid legal basis for processing personal data look like under Europe’s updated privacy rules? It may sound like an abstract concern but for online services that rely on things being done with user data in order to monetize free-to-access content this is a key question now the region’s General Data Protection Regulation is firmly fixed in place.

The GDPR is actually clear about consent. But if you haven’t bothered to read the text of the regulation, and instead just go and look at some of the self-styled consent management platforms (CMPs) floating around the web since May 25, you’d probably have trouble guessing it.

Confusing and/or incomplete consent flows aren’t yet extinct, sadly. But it’s fair to say those that don’t offer full opt-in choice are on borrowed time.

Because if your service or app relies on obtaining consent to process EU users’ personal data — as many free at the point-of-use, ad-supported apps do — then the GDPR states consent must be freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous.

That means you can’t bundle multiple uses for personal data under a single opt-in.

Nor can you obfuscate consent behind opaque wording that doesn’t actually specify the thing you’re going to do with the data.

You also have to offer users the choice not to consent. So you cannot pre-tick all the consent boxes that you really wish your users would freely choose — because you have to actually let them do that.

It’s not rocket science but the pushback from certain quarters of the adtech industry has been as awfully predictable as it’s horribly frustrating.

This has not gone unnoticed by consumers either. Europe’s Internet users have been filing consent-based complaints thick and fast this year. And a lot of what is being claimed as ‘GDPR compliant’ right now likely is not.

So, some six months in, we’re essentially in a holding pattern waiting for the regulatory hammers to come down.

But if you look closely there are some early enforcement actions that show some consent fog is starting to shift.

Yes, we’re still waiting on the outcomes of major consent-related complaints against tech giants. (And stockpile popcorn to watch that space for sure.)

But late last month French data protection watchdog, the CNIL, announced the closure of a formal warning it issued this summer against drive-to-store adtech firm, Fidzup — saying it was satisfied it was now GDPR compliant.

Such a regulatory stamp of approval is obviously rare this early in the new legal regime.

So while Fidzup is no adtech giant its experience still makes an interesting case study — showing how the consent line was being crossed; how, working with CNIL, it was able to fix that; and what being on the right side of the law means for a (relatively) small-scale adtech business that relies on consent to enable a location-based mobile marketing business.

From zero to GDPR hero?

Fidzup’s service works like this: It installs kit inside (or on) partner retailers’ physical stores to detect the presence of user-specific smartphones. At the same time it provides an SDK to mobile developers to track app users’ locations, collecting and sharing the advertising ID and wi-fi ID of users’ smartphone (which, along with location, are judged personal data under GDPR.)

Those two elements — detectors in physical stores; and a personal data-gathering SDK in mobile apps — come together to power Fidzup’s retail-focused, location-based ad service which pushes ads to mobile users when they’re near a partner store. The system also enables it to track ad-to-store conversions for its retail partners.

The problem Fidzup had, back in July, was that after an audit of its business the CNIL deemed it did not have proper consent to process users’ geolocation data to target them with ads.

Fidzup says it had thought its business was GDPR compliant because it took the view that app publishers were the data processors gathering consent on its behalf; the CNIL warning was a wake up call that this interpretation was incorrect — and that it was responsible for the data processing and so also for collecting consents.

The regulator found that when a smartphone user installed an app containing Fidzup’s SDK they were not informed that their location and mobile device ID data would be used for ad targeting, nor the partners Fidzup was sharing their data with.

CNIL also said users should have been clearly informed before data was collected — so they could choose to consent — instead of information being given via general app conditions (or in store posters), as was the case, after the fact of the processing.

It also found users had no choice to download the apps without also getting Fidzup’s SDK, with use of such an app automatically resulting in data transmission to partners.

Fidzup’s approach to consent had also only been asking users to consent to the processing of their geolocation data for the specific app they had downloaded — not for the targeted ad purposes with retail partners which is the substance of the firm’s business.

So there was a string of issues. And when Fidzup was hit with the warning the stakes were high, even with no monetary penalty attached. Because unless it could fix the core consent problem, the 2014-founded startup might have faced going out of business. Or having to change its line of business entirely.

Instead it decided to try and fix the consent problem by building a GDPR-compliant CMP — spending around five months liaising with the regulator, and finally getting a green light late last month.

A core piece of the challenge, as co-founder and CEO Olivier Magnan-Saurin tells it, was how to handle multiple partners in this CMP because its business entails passing data along the chain of partners — each new use and partner requiring opt-in consent.

“The first challenge was to design a window and a banner for multiple data buyers,” he tells TechCrunch. “So that’s what we did. The challenge was to have something okay for the CNIL and GDPR in terms of wording, UX etc. And, at the same time, some things that the publisher will allow to and will accept to implement in his source code to display to his users because he doesn’t want to scare them or to lose too much.

“Because they get money from the data that we buy from them. So they wanted to get the maximum money that they can, because it’s very difficult for them to live without the data revenue. So the challenge was to reconcile the need from the CNIL and the GDPR and from the publishers to get something acceptable for everyone.”

As a quick related aside, it’s worth noting that Fidzup does not work with the thousands of partners an ad exchange or demand-side platform most likely would be.

Magnan-Saurin tells us its CMP lists 460 partners. So while that’s still a lengthy list to have to put in front of consumers — it’s not, for example, the 32,000 partners of another French adtech firm, Vectaury, which has also recently been on the receiving end of an invalid consent ruling from the CNIL.

In turn, that suggests the ‘Fidzup fix’, if we can call it that, only scales so far; adtech firms that are routinely passing millions of people’s data around thousands of partners look to have much more existential problems under GDPR — as we’ve reported previously re: the Vectaury decision.

No consent without choice

Returning to Fidzup, its fix essentially boils down to actually offering people a choice over each and every data processing purpose, unless it’s strictly necessary for delivering the core app service the consumer was intending to use.

Which also means giving app users the ability to opt out of ads entirely — and not be penalized by not being able to use the app features itself.

In short, you can’t bundle consent. So Fidzup’s CMP unbundles all the data purposes and partners to offer users the option to consent or not.

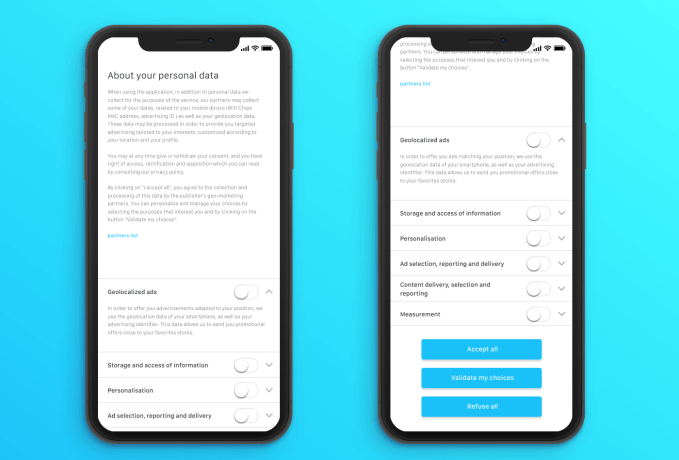

“You can unselect or select each purpose,” says Magnan-Saurin of the now compliant CMP. “And if you want only to send data for, I don’t know, personalized ads but you don’t want to send the data to analyze if you go to a store or not, you can. You can unselect or select each consent. You can also see all the buyers who buy the data. So you can say okay I’m okay to send the data to every buyer but I can also select only a few or none of them.”

“What the CNIL ask is very complicated to read, I think, for the final user,” he continues. “Yes it’s very precise and you can choose everything etc. But it’s very complete and you have to spend some time to read everything. So we were [hoping] for something much shorter… but now okay we have something between the initial asking for the CNIL — which was like a big book — and our consent collection before the warning which was too short with not the right information. But still it’s quite long to read.”

Fidzup’s CNIL approved GDPR-compliant consent management platform

“Of course, as a user, I can refuse everything. Say no, I don’t want my data to be collected, I don’t want to send my data. And I have to be able, as a user, to use the app in the same way as if I accept or refuse the data collection,” he adds.

He says the CNIL was very clear on the latter point — telling it they could not require collection of geolocation data for ad targeting for usage of the app.

“You have to provide the same service to the user if he accepts or not to share his data,” he emphasizes. “So now the app and the geolocation features [of the app] works also if you refuse to send the data to advertisers.”

This is especially interesting in light of the ‘forced consent’ complaints filed against tech giants Facebook and Google earlier this year.

These complaints argue the companies should (but currently do not) offer an opt-out of targeted advertising, because behavioural ads are not strictly necessary for their core services (i.e. social networking, messaging, a smartphone platform etc).

Indeed, data gathering for such non-core service purposes should require an affirmative opt-in under GDPR. (An additional GDPR complaint against Android has also since attacked how consent is gathered, arguing it’s manipulative and deceptive.)

Asked whether, based on his experience working with the CNIL to achieve GDPR compliance, it seems fair that a small adtech firm like Fidzup has had to offer an opt-out when a tech giant like Facebook seemingly doesn’t, Magnan-Saurin tells TechCrunch: “I’m not a lawyer but based on what the CNIL asked us to be in compliance with the GDPR law I’m not sure that what I see on Facebook as a user is 100% GDPR compliant.”

“It’s better than one year ago but [I’m still not sure],” he adds. “Again it’s only my feeling as a user, based on the experience I have with the French CNIL and the GDPR law.”

Facebook of course maintains its approach is 100% GDPR compliant.

Even as data privacy experts aren’t so sure.

One thing is clear: If the tech giant was forced to offer an opt out for data processing for ads it would clearly take a big chunk out of its business — as a sub-set of users would undoubtedly say no to Zuckerberg’s “ads”. (And if European Facebook users got an ads opt out you can bet Americans would very soon and very loudly demand the same, so…)

Bridging the privacy gap

In Fidzup’s case, complying with GDPR has had a major impact on its business because offering a genuine choice means it’s not always able to obtain consent. Magnan-Saurin says there is essentially now a limit on the number of device users advertisers can reach because not everyone opts in for ads.

Although, since it’s been using the new CMP, he says a majority are still opting in (or, at least, this is the case so far) — showing one consent chart report with a ~70:30 opt-in rate, for example.

He expresses the change like this: “No one in the world can say okay I have 100% of the smartphones in my data base because the consent collection is more complete. No one in the world, even Facebook or Google, could say okay, 100% of the smartphones are okay to collect from them geolocation data. That’s a huge change.”

“Before that there was a race to the higher reach. The biggest number of smartphones in your database,” he continues. “Today that’s not the point.”

Now he says the point for adtech businesses with EU users is figuring out how to extrapolate from the percentage of user data they can (legally) collect to the 100% they can’t.

And that’s what Fidzup has been working on this year, developing machine learning algorithms to try to bridge the data gap so it can still offer its retail partners accurate predictions for tracking ad to store conversions.

“We have algorithms based on the few thousand stores that we equip, based on the few hundred mobile advertising campaigns that we have run, and we can understand for a store in London in… sports, fashion, for example, how many visits we can expect from the campaign based on what we can measure with the right consent,” he says. “That’s the first and main change in our market; the quantity of data that we can get in our database.”

“Now the challenge is to be as accurate as we can be without having 100% of real data — with the consent, and the real picture,” he adds. “The accuracy is less… but not that much. We have a very, very high standard of quality on that… So now we can assure the retailers that with our machine learning system they have nearly the same quality as they had before.

“Of course it’s not exactly the same… but it’s very close.”

Having a CMP that’s had regulatory ‘sign-off’, as it were, is something Fidzup is also now hoping to turn into a new bit of additional business.

“The second change is more like an opportunity,” he suggests. “All the work that we have done with CNIL and our publishers we have transferred it to a new product, a CMP, and we offer today to all the publishers who ask to use our consent management platform. So for us it’s a new product — we didn’t have it before. And today we are the only — to my knowledge — the only company and the only CMP validated by the CNIL and GDPR compliant so that’s useful for all the publishers in the world.”

It’s not currently charging publishers to use the CMP but will be seeing whether it can turn it into a paid product early next year.

How then, after months of compliance work, does Fidzup feel about GDPR? Does it believe the regulation is making life harder for startups vs tech giants — as is sometimes suggested, with claims put forward by certain lobby groups that the law risks entrenching the dominance of better resourced tech giants. Or does he see any opportunities?

In Magnan-Saurin’s view, six months in to GDPR European startups are at an R&D disadvantage vs tech giants because U.S. companies like Facebook and Google are not (yet) subject to a similarly comprehensive privacy regulation at home — so it’s easier for them to bag up user data for whatever purpose they like.

Though it’s also true that U.S. lawmakers are now paying earnest attention to the privacy policy area at a federal level. (And Google’s CEO faced a number of tough questions from Congress on that front just this week.)

“The fact is Facebook-Google they own like 90% of the revenue in mobile advertising in the world. And they are American. So basically they can do all their research and development on, for example, American users without any GDPR regulation,” he says. “And then apply a pattern of GDPR compliance and apply the new product, the new algorithm, everywhere in the world.

“As a European startup I can’t do that. Because I’m a European. So once I begin the research and development I have to be GDPR compliant so it’s going to be longer for Fidzup to develop the same thing as an American… But now we can see that GDPR might be beginning a ‘world thing’ — and maybe Facebook and Google will apply the GDPR compliance everywhere in the world. Could be. But it’s their own choice. Which means, for the example of the R&D, they could do their own research without applying the law because for now U.S. doesn’t care about the GDPR law, so you’re not outlawed if you do R&D without applying GDPR in the U.S. That’s the main difference.”

He suggests some European startups might relocate R&D efforts outside the region to try to workaround the legal complexity around privacy.

“If the law is meant to bring the big players to better compliance with privacy I think — yes, maybe it goes in this way. But the first to suffer is the European companies, and it becomes an asset for the U.S. and maybe the Chinese… companies because they can be quicker in their innovation cycles,” he suggests. “That’s a fact. So what could happen is maybe investors will not invest that much money in Europe than in U.S. or in China on the marketing, advertising data subject topics. Maybe even the French companies will put all the R&D in the U.S. and destroy some jobs in Europe because it’s too complicated to do research on that topics. Could be impacts. We don’t know yet.”

But the fact of GDPR enforcement having — perhaps inevitably — started small, with so far a small bundle of warnings against relative data minnows, rather than any swift action against the industry dominating adtech giants, that’s being felt as yet another inequality at the startup coalface.

“What’s sure is that the CNIL started to send warnings not to Google or Facebook but to startups. That’s what I can see,” he says. “Because maybe it’s easier to see I’m working on GDPR and everything but the fact is the law is not as complicated for Facebook and Google as it is for the small and European companies.”