US regulators shouldn’t be sitting on their hands while the 50+ state, federal and congressional antitrust investigations of Google to grind along, search rival DuckDuckGo argues.

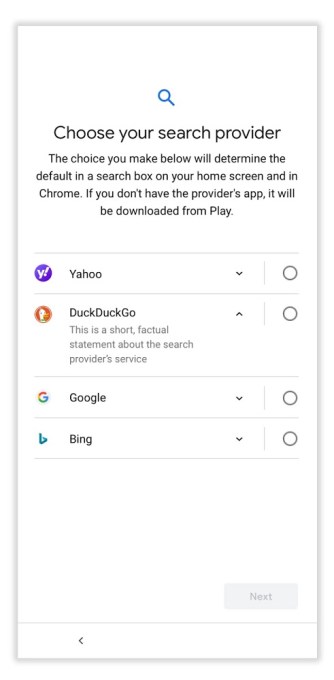

It’s put out a piece of research today that suggests choice screens which let smartphone users choose from a number of search engines to be their device default — aka “preference menus” as DuckDuckGo founder Gabriel Weinberg prefers to call them — offer an easy and quick win for regulators to reboot competition in the search space by rebalancing markets right now.

“If designed properly we think [preference menus] are a quick and effective key piece in the puzzle for a good remedy,” Weinberg tells TechCrunch. “And that’s because it finally enables people to change the search defaults across the entire device which has been difficult in the past… It’s at a point, during device set-up, where you can promote the users to take a moment to think about whether they want to try out an alternative search engine.”

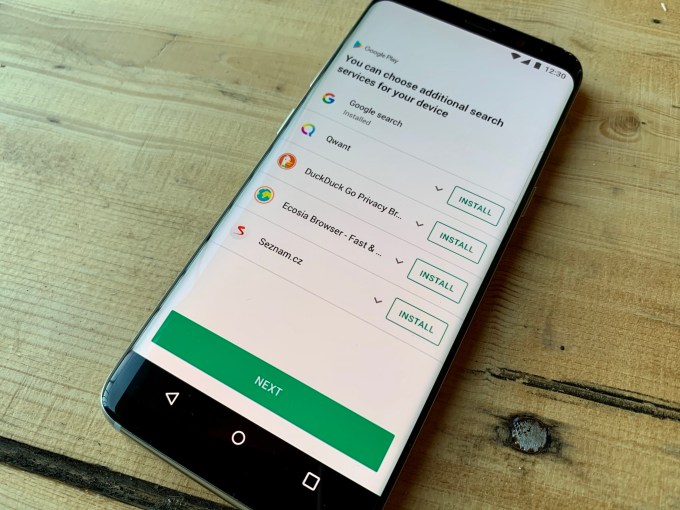

Google is already offering such a choice (example below) to Android users in Europe, following an EU antitrust decision against Android last year.

DuckDuckGo is concerned US regulators aren’t thinking pro-actively enough about remedies for competition in the US search market — and is hoping to encourage more of a lean-in approach to support boosting diversity so that rivals aren’t left waiting years for the courts to issue judgements before any relief is possible.

In a survey of Internet users which it commissioned, polling more than 3,400 adults in the US, UK, Germany and Australia, people were asked to respond to a 4-choice screen design, based on an initial Google Android remedy proposal, as well as an 8-choice variant.

“We found that in each surveyed country, people select the Google alternatives at a rate that could increase their collective mobile market share by 300%-800%, with overall mobile search market share immediately changing by over 10%,” it writes [emphasis its].

Survey takers were also asked about factors that motivate them to switch search engines — with the number one reason given being a better quality of search results, and the next reason being if a search engine doesn’t track their searches or data.

Of course DuckDuckGo stands to gain from any pro-privacy switching, having built an alternative search business by offering non-tracked searches supported by contextual ads. Its model directly contrasts with Google’s, which relies on pervasive tracking of Internet users to determine which ads to serve.

But there’s plenty of evidence consumers hate being tracked. Not least the rise in use of tracker blockers.

“Using the original design puzzle [i.e. that Google devised] we saw a lot of people selecting alternative search engines and we think it would go up from there,” says Weinberg. “But even initially a 10% market share change is really significant.”

He points to regulatory efforts in Europe and also Russia which have resulted in antitrust decisions and enforcements against Google — and where choice screens are already in use promoting alternative search engine choices to Android users.

He also notes that regulators in Australia and the UK are pursuing choice screens — as actual or potential remedies for rebalancing the search market.

Russia has the lead here, with its regulator — the FAS — slapping Google with an order against bundling its services with Android all the way back in 2015, a few months after local search giant Yandex filed a complaint. A choice screen was implemented in 2017 and Russia’s homegrown Internet giant has increased its search market share on Android devices as a result. Google continues to do well in Russia. But the result is greater diversity in the local search market, as a direct result of implementing a choice screen mechanism.

“We think that all regulatory agencies that are now considering search market competition should really implement this remedy immediately,” says Weinberg. “They should do other things… as well but I don’t see any reason why one should wait on not implementing this because it would take a while to roll out and it’s a good start.”

Of course US regulators have yet to issue any antitrust findings against Google — despite there now being tens of investigations into “potential monopolistic behavior”. And Weinberg concedes that US regulators haven’t yet reached the stage of discussing remedies.

“It feels at a very investigatory stage,” he agrees. “But we would like to accelerate that… As well as bigger remedial changes — similar to privacy and how we’re pushing Do Not Track legislation — as something you can do right now as kind of low hanging fruit. I view this preference menu in the same way.”

“It’s a very high leverage thing that you can do immediately to move market share and increase search competition and so one should do it faster and then take the things that need to be slower slower,” he adds, referring to more radical possible competition interventions — such as breaking a business up.

There is certainly growing concern among policymakers around the world that the current modus operandi of enforcing competition law has failed to keep pace with increasingly powerful technology-driven businesses and platforms — hence ‘winner takes all’ skews which exist in certain markets and marketplaces, reducing choice for consumers and shrinking opportunities for startups to compete.

This concern was raised as a question for Europe’s competition chief, Margrethe Vestager, during her hearing in front of the EU parliament earlier this month. She pointed to the Commission’s use of interim measures in an ongoing case against chipmaker Broadcom as an example of how the EU is trying to speed up its regulatory response, noting it’s the first time such an application has been made for two decades.

In a press conference shortly afterwards, to confirm the application of EU interim measures against Broadcom, Vestager added: “Interim measures are one way to tackle the challenge of enforcing our competition rules in a fast and effective manner. This is why they are important. And especially that in fast moving markets. Whenever necessary I’m therefore committed to making the best possible use of this important tool.”

Weinberg is critical of Google’s latest proposals around search engine choice in Europe — after it released details of its idea to ‘evolve’ the search choice screen — by applying an auction model, starting early next year. Other rivals, such as French pro-privacy engine Qwant, have also blasted the proposal.

Clearly, how choice screens are implemented is key to their market impact.

“The way the current design is my read is smaller search engines, including us and including European search engines will not be on the screen long term the way it’s set up,” says Weinberg. “There will need to be additional changes to get the effects that we were seeing in our studies we made.

“There’s many reasons why us and others would not be those highest bidders,” he says of the proposed auction. “But needless to say the bigger companies can weigh outbid the smaller ones and so there are alternative ways to set this up.”