The UK government has once again amped up its attacks on tech platforms’ use of end-to-end encryption, and called for International co-operation to regulate the Internet so that it cannot be used as a “safe space” for extremists to communicate and spread propaganda online.

The comments by UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, and Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, come in the wake of another domestic terrorist attack, the third since March, after a group of terrorists used a van to plow down pedestrians in London Bridge on Saturday evening, before going on a knife rampage attacking people in streets and bars.

Speaking outside Downing Street yesterday, May swung the finger of blame at “big” Internet companies — criticizing platform giants for providing “safe spaces” for extremists to spread messages of hate online.

Early reports have suggested the attackers may have used YouTube to access extremist videos.

“We cannot allow this ideology the safe space it needs to breed. Yet that is precisely what the internet – and the big companies that provide internet-based services – provide,” May said. “We need to work with allied, democratic governments to reach international agreements that regulate cyberspace to prevent the spread of extremism and terrorist planning. And we need to do everything we can at home to reduce the risks of extremism online.”

“We need to deprive the extremists of their safe spaces online,” she added.

Speaking in an interview on ITV’s Peston on Sunday program yesterday, UK Home Secretary Amber Rudd further fleshed out the prime minister’s comments. She said the government wants to do more to stop the way young men are being “groomed” into radicalization online — including getting tech companies to do more to take down extremist material, and also to limit access to end-to-end encryption.

Rudd also attacked tech firms’ use of encryption in the wake of the Westminster terror attack in March, although the first round of meetings she held with Internet companies including Facebook, Google and Twitter in the wake of that earlier attack apparently focused on pushing for them to develop tech tools to automatically identify extremist content and block it before it is widely disseminated.

The prime minister also made a push for international co-operation on online extremism during the G7 summit last month — coming away with a joint statement to put pressure on tech firms to do more. “We want companies to develop tools to identify and remove harmful materials automatically,” May said then.

Though it is far from clear whether this geopolitical push will translate into anything more than a few headlines — given tech firms are already using and developing tools for automating takedowns. And the G7 nations apparently did not ink any specific policy proposals — such as on co-ordinated fines for social media takedown failures.

On the extremist content front, pressure has certainly been growing across Europe for tech platforms to do more — including proposals such as a draft law in Germany which does suggest fines of up to €50 million for social media firms that fail to promptly takedown illegal hate speech, for example. While last month a UK parliamentary committee urged the government to consider a similar approach — and UK ministers are apparently open to the idea.

But the notion of the UK being able to secure international agreement on harmonizing content regulation online across borders seems entirely fanciful — given different legal regimes vis-a-vis free speech, with the US having constitutional protections for hate speech vs hate speech being illegal in certain European countries, for example.

Again, these comments in the immediate aftermath of an attack seem mostly aimed at diverting attention from tougher political questions — including over domestic police resourcing; over UK ally Saudi Arabia’s financial support for extremism; and why known hate preachers were apparently allowed to continue broadcasting their message in the UK…

“Blaming social media platforms is politically convenient but intellectually lazy,” tweeted professor Peter Neumann, director of the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence. “Most jihadists are now using end-to-end encrypted messenger platforms e.g. Telegram. This has not solved problem, just made it different.”

Responding to the government’s comments in a statement, Facebook’s Simon Milner, UK director of policy, said: “We want to provide a service where people feel safe. That means we do not allow groups or people that engage in terrorist activity, or posts that express support for terrorism. We want Facebook to be a hostile environment for terrorists. Using a combination of technology and human review, we work aggressively to remove terrorist content from our platform as soon as we become aware of it — and if we become aware of an emergency involving imminent harm to someone’s safety, we notify law enforcement. Online extremism can only be tackled with strong partnerships. We have long collaborated with policymakers, civil society, and others in the tech industry, and we are committed to continuing this important work together.”

Facebook has faced wider criticism of its approach to content moderation in recent months — and last month announced it would be adding an additional 3,000 staff to its team of reviewers, bringing the global total to 7,500.

In another reaction statement Twitter’s UK head of public policy, Nick Pickles, added: “Terrorist content has no place on Twitter. We continue to expand the use of technology as part of a systematic approach to removing this type of content. We will never stop working to stay one step ahead and will continue to engage with our partners across industry, government, civil society and academia.”

Twitter details how many terrorism-related accounts it suspends in its Transparency Report — the vast majority of which it says it identifies using its own tools, rather than relying on user reports.

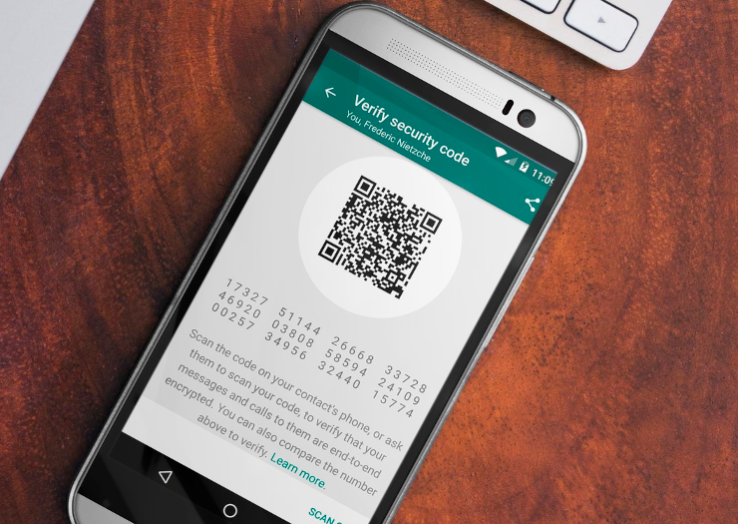

On the controversial topic of limiting end-to-end encryption, a report in The Sun newspaper last month suggested a re-elected Conservative government would prioritize a decryption law to force social media platforms which are using e2e encryption to effectively backdoor these systems so that they could hand over decrypted data when served a warrant.

The core legislation for this decrypt law already exists, aka the Investigatory Powers Act — which was passed at the end of last year. Following the General Election on June 8, a new UK Parliament will just need to agree the supplementary technical capability regulation which places a legal obligation on ISPs and communication service providers to maintain the necessary capability to be able to provide decrypted data on request (albeit, without providing technical detail on how any of this will happen in practice).

Given Rudd’s comments now on limiting e2e encryption it seems clear the preferred route for an incoming Conservative UK government will be to pressure tech firms not to use strong encryption to safeguard user data in — backed up by the legal muscle of the country having what has been widely interpreted as a decrypt law.

However such moves will clearly undermine online security at a time when the risks of doing so are becoming increasingly clear. As crypto expert Bruce Schneier told us recently, the only way for the UK government to get “the access it wants is to destroy everyone’s security”.

Moreover, a domestic decrypt law is unlikely to have any impact on e2e encrypted services — such as Telegram — which are not based in the UK, and would therefore surely not consider themselves bound by UK legal jurisdiction.

And even if the UK government forced ISPs and app stores to block access to all services that do not comply with its decryption requirements, there would still be workarounds for terrorists to continue accessing strongly encrypted services. Even as law abiding users of mainstream tech platforms risk having their security undermined by political pressure on strong encryption.

Commenting on the government’s planned Internet crackdown, the Open Rights Group had this to say: “It is disappointing that in the aftermath of this attack, the government’s response appears to focus on the regulation of the Internet and encryption. This could be a very risky approach. If successful, Theresa May could push these vile networks into even darker corners of the web, where they will be even harder to observe.

“But we should not be distracted: the Internet and companies like Facebook are not a cause of this hatred and violence, but tools that can be abused. While governments and companies should take sensible measures to stop abuse, attempts to control the Internet is not the simple solution that Theresa May is claiming.”

Meanwhile, asked about his support for encryption back in September 2015 — given the risks of his messaging platform being used by terrorists — Telegram founder Pavel Durov said: “I think that privacy, ultimately, and our right for privacy is more important than our fear of bad things happening, like terrorism… Ultimately the ISIS will always find a way to communicate within themselves. And if any means of communication turns out to be not secure for them, then they switch to another one. So I don’t think we’re actually taking part in this activities. I don’t think we should feel guilty about this. I still think we’re doing the right thing — protecting our users privacy.”